Josh Ward, left, and Bob Miller join other workers in harvesting Merlot grapes in November 2016 at Lake Roosevelt vineyard near Creston, Washington. The south-facing vineyard sits atop a cliff with basalt walls behind it. High above the cliff on the plateau stretch miles of wheat fields. Below it lies Lake Roosevelt, a Columbia River reservoir built behind Grand Coulee Dam. (Shannon Dininny/Good Fruit Grower)

In the spring of 1994, Michael Haig earned a crash course in viticulture when he and 30 of his high school classmates planted Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon wine grapes in North Central Washington’s remote Jump Canyon.

The following spring, while Haig was away at college, another group of high school seniors added Cabernet Franc and Pinot Noir vines.

Haig’s parents had the notion to plant the vineyard, under the guidance of longtime Washington State University viticulturist Robert Wample. For years, they sold their grapes to a handful of Washington’s better-known wineries, among them Walla Walla Vintners, Canoe Ridge and L’Ecole.

After college, though, with degrees in economics and accounting in hand, Haig grew interested in producing his own wine.

He took courses through University of California, Davis, began producing small batches and, by 2006, was using all of the vineyard’s grapes himself to produce estate wines.

Michael Haig, viticulturist, winemaker and co-owner of Lake Roosevelt Wine Co., loads freshly picked Merlot grapes onto a rig to transport downhill to the winery. (Shannon Dininny/Good Fruit Grower)

Today, Lake Roosevelt Vineyard and Winery produces roughly 2,400 cases annually from a facility overlooking the sprawling reservoir that shares its name — with nary another vineyard or winery in sight.

Despite the lonesome location, the winery produces award-winning wines, with growing conditions that more closely mimic those found in California’s Napa Valley than any other part of Washington, Haig said. “Our growing season is a lot smoother. We just don’t have those temperature extremes between cold and hot,” he said.

The result is intense berries and balanced wines.

“The key is to educate people that you can grow grapes elsewhere in the state,” he said. “It’s about educating the consumer that there are multiple ways you can grow a Merlot in Washington state and still have it be a great Merlot.”

That’s a message Washington’s wine industry increasingly embraces as the number of wineries — and vineyards — continues to grow.

Location, location, location

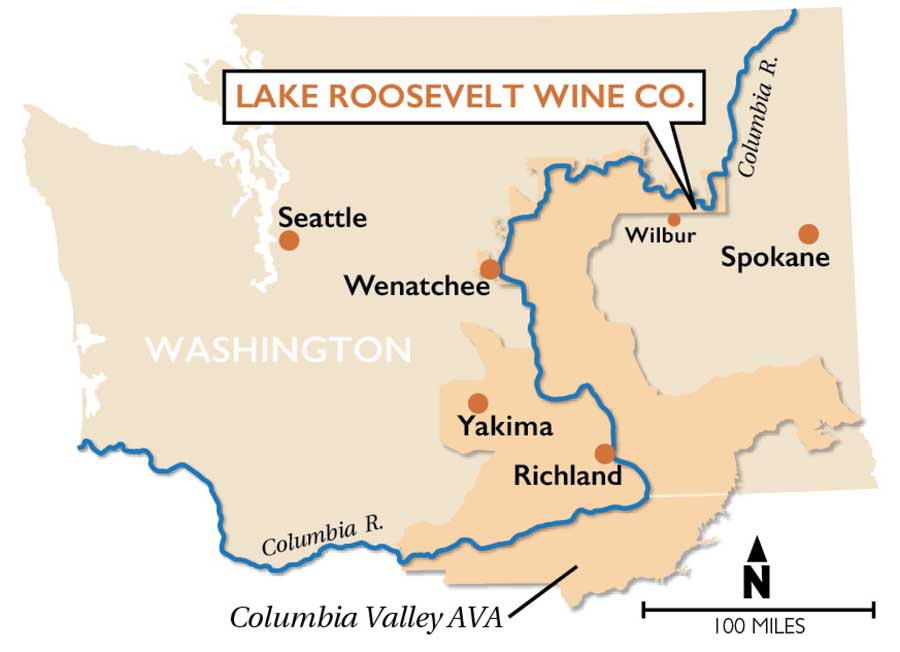

(Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower illustration)

As it spills from its headwaters in the Canadian Rocky Mountains to its mouth at the Pacific Ocean, the Columbia River travels south and west through Washington, forming most of the border with Oregon.

Overall, the Columbia River basin feeds thousands of acres of crops in the Pacific Northwest — including 50,000-plus acres of wine grapes in Washington alone.

Most of those vineyards sit in the lower two-thirds of a federally recognized American Viticultural Area known as the Columbia Valley AVA and in sub-appellations fast gaining their own renown for high-quality wine. (Think Yakima Valley, Red Mountain, Walla Walla Valley and Wahluke Slope, just to name a few.)

But if you look closely at a map, there is one point, in the far northern reaches of the appellation, where the mighty Columbia makes a sharp turn and flows straight north. It’s a remote area of craggy granite and basalt cliffs overlooking the deep reservoir, Lake Roosevelt, formed behind monolithic Grand Coulee Dam.

Tucked amid those cliffs, at an elevation of 1,800 feet, sit Haig’s 16 acres of Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and Cabernet Franc wine grapes. He pulled out the Pinot Noir vines two years ago when the market price dropped.

The massive lake, which takes time to warm, offers a marine effect typically associated with the ocean, cooling the vineyard during the warmer summer months.

By mid-September, with the lake finally hitting temperatures in the upper 70s and heat radiating from the basalt and granite cliffs, the vineyard absorbs more heat.

Haig has seen few spikes in heat or cold, though last year the vineyard recorded more 100-degree days than it all the prior years combined — 16 days, compared with 12-14 days total over the vineyard’s history.

“It’s just such a radically different climate up here. You get fully ripe fruit without high sugar, right around 24 Brix,” he said. “It really leads to a well-balanced fruit without having to adjust the mustering. We’re really showcasing the vineyard, and you’re not having to deal with high alcohol on the wine.”

Thanks to the kink in the river turning north, the vineyard faces south.

High on a cliff overlooking Lake Roosevelt in North Central Washington, a yurt serves as the tasting room for Lake Roosevelt Wine Co. and its Whitestone Winery label. The lake, a reservoir behind Grand Coulee Dam on the Columbia River, helps regulate air temperatures in an area that can experience sub-zero winter conditions. (Shannon Dininny/Good Fruit Grower)

The Cabernet Sauvignon gets about two hours more sunlight each day than the Cabernet Franc, which gets the last sun in the morning and the first shade in the afternoon.

Haig said he’s learned to hang it until the canopy drops, to ensure no vegetative characteristics.

“It’s one of the grapes that, the longer I can keep it on, the less chance of getting bell pepper,” he said. His target is about 2.5 tons per acre for each variety. “We’re happy with the consistency and quality of the wines there.”

A natural spring smashed between the basalt and granite layers of the cliff feeds the vineyard. Haig merely opens and closes a gravity-fed pipe when he wants to irrigate and recharges a water tank during down time.

With no full-time employees, his biggest issue is labor. Haig has no trouble finding workers at harvest, though it’s pricey at around $350 per ton, but to prune the vines, “it’s pretty much me.”

“If we want to replace that Pinot block, labor would be our toughest issue,” he said. “With an established vineyard, it’s a lot easier; you don’t have as much labor involved in just maintaining the vineyard. But those first four to five years, it’s harder.”

New horizons?

Alan Busacca, a soil scientist and consultant who has assisted with and written Pacific Northwest federal AVA applications, views the northern reaches of the Columbia Valley AVA as untapped ground for wine grapes.

Given its size, Lake Roosevelt would provide similar benefits as another lake in the Columbia Valley AVA, Lake Chelan, which at 1,200 feet deep, consumes solar energy in the summer, cooling the surrounding area, and gives that energy back in the winter.

And when Washington’s pioneering viticulture researcher Walter Clore and others drafted the Columbia Valley AVA application, they included the Lake Roosevelt region for a reason, Busacca said.

“Clore seemed to have a real nose for air flow patterns that will protect the vines and naturally warm locations where there will be minimal damage,” he said. “They were onto something in terms of including and defining the Lake Roosevelt area.”

In addition, the far northern region of the appellation in the vicinity of Grand Coulee Dam and downstream offers a different soil profile than the rest of the Columbia plateau. Bedrock forming the soils is granitic, compared to the coarse gravel and sand from basalt deposits from ice age floods farther south, Busacca said.

“This area is pretty heavily developed for orchards, but not yet for vineyards,” he said. “It’s an area that I really like that hasn’t yet seen development.”

Haig, too, notes the potential there, and points to historical agricultural uses near his own vineyard.

Though the top of the bench, 2 miles up from the river, features wheat fields for miles, the natural spring water near the cliffs enabled residents in the early 1900s to grow tree fruit and grapes where Lake Roosevelt now sits, before Grand Coulee Dam was built. (Haig has a 1916 photo of a grape harvest there.)

Jump Canyon was even named after the Jump family, the largest bootlegging operation in Washington during Prohibition, and there are still old orchard trees and Concord grapes hidden in the neighboring hillside amid evergreen trees, he said.

“If global warming keeps coming the way it’s coming, we’re really in a great position,” he said. “I’d love to see more wineries here. We could have the only wine tasting trail followed by boat.” •

Lake Roosevelt Wine Co.

Lake Roosevelt Wine Co. produces three red varieties — Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and Cabernet Franc — as well as red blends. Its Whitestone Winery label, named for a giant stone in the lake, serves as its estate label, enabling the winery to pursue other ventures, such as fruit distilling, under the larger Lake Roosevelt line.

In addition to its wine club, the winery sells online and to the 6,000 visitors it sees from May to Sept. 30 each year, with those traveling by car largely coming from Spokane, Washington, little more than an hour’s drive away. A flagpole also helps alert boaters on Lake Roosevelt as to whether the winery is open for tasting to be shuttled up from the shoreline.

During those months, co-owner Michael Haig serves as viticulturist, winemaker, sales guy and cook — summer offerings include paella dinners, pig roasts and Sunday brunches.

\He also is looking to open a winter tasting room along Highway 20, where he already owns property in the town of Wilbur, Washington.

– by Shannon Dininny

Leave A Comment