—by Matt Milkovich

If you’re like most fruit growers these days, you’d probably love to find a new source of labor to tap into. If so, there’s a group you might not have considered: autistic people.

Autistic individuals probably aren’t going to solve all of your labor problems, but they can bring unique strengths to your operation if you can offer accommodations that set them up for success.

“There has to be a level of compassion and patience with employing someone on the spectrum,” said New York apple grower Danielle Teeple. “When things change, there’s always an adjustment.”

Laurel Hoekman, who runs a company in Holland, Michigan, that provides employment training for autistic people, discussed tapping the potential of employees on the autism spectrum during the Great Lakes Fruit, Vegetable, and Farm Market EXPO in Grand Rapids, Michigan, in December. She said people on the autism spectrum are an untapped employee pool, and fruit growers, in many ways, are an untapped employer pool, so the two groups might be a good fit for each other.

Autism is a condition related to brain development that impacts how a person perceives and socializes with others, which can cause challenges in social interactions and communication. The term “spectrum” refers to a wide range of symptoms and severity, and it can encompass a range of abilities and challenges, Hoekman said.

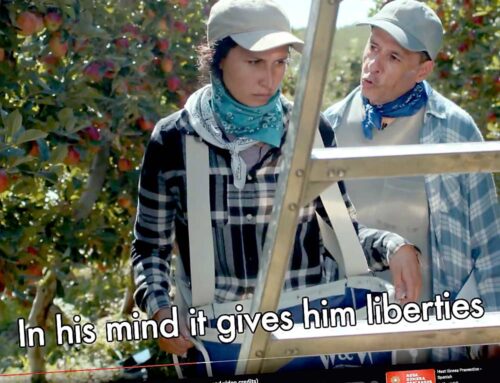

Danielle and Frank Teeple, who grow 400 acres of apples in Wolcott, New York, have direct experience with this particular group of workers. Their son Philip, 14, is autistic. So are two of their employees.

Danielle, who has a background in special education, said farming, with its cyclical nature and repetitive tasks, such as trimming, pruning and mowing, can be a great fit for autistic individuals.

“Many individuals on the spectrum don’t like change,” she said. “And aside from the weather, agriculture is pretty darn the same.”

Her son Philip loves to plow and disc, and he will pick root suckers for hours. He’s also interested in hydroponics, aquaponics, fertilization and tree breeding. When he was 4, he took an engine apart and put it back together, even though “no one ever showed him how,” Danielle said.

“He’s absolutely brilliant,” she said. “I wish I could get into his brain.”

Many people on the spectrum have a “fabulous memory for details,” and a comprehensive knowledge of topics that interest them, Hoekman said.

“I’m often jealous of autistic people, who have a phenomenal memory for facts and statistics,” she said.

Hoekman recalled one of her clients who got a job in a grocery store produce department. He researched every single produce item and could tell customers exactly what it was, where it was from and how to prepare it. This characteristic can be a tremendous resource for employers, she said.

But working with autistic people can require sympathy and strategy. They might exhibit repetitive movements or verbal tics. They tend to have a hard time reading nonverbal cues, and they can interpret things very literally. They often prefer to work alone. Many autistic people are extra-sensitive to light, sound and temperature, to the point where they can’t focus, Hoekman said.

But there are things employers can do to help. If the employee has difficulty managing temperature changes, for example, you could put them to work in a greenhouse, where the temperature stays more or less the same. If the problem is noise, let them work with noise-canceling headphones or take breaks in a quiet place. Tasks that involve lifting, pushing and pulling — and there are plenty of these on farms — can help reset their sensory systems, Hoekman said.

One of the “hallmark characteristics” of autism, she said, is difficulty with executive functioning — brain activities such as planning, organizing, sequencing and prioritizing. Simple strategies like setting alarms or making task lists can help keep things on track.

Another hallmark is difficulty making eye contact. You’re better off asking an autistic employee to restate what you said rather than forcing them to look at you. They often don’t get the point of small talk, either. They just want to get to the “meat of the conversation,” Hoekman said.

When working with someone on the spectrum, employers bear much of the responsibility for the success of the interaction. They must define their expectations when assigning a task. Let the employee know how long it will take and when there’s going to be a transition, she said.

“There’s often a little bit of fear about how to deal with a person on the spectrum,” Danielle Teeple said. “They’re just different. They’re super smart and have some quirks, but they’re human beings.”

The Teeple Farms workforce is a mix of local, migrant and H-2A workers. They’ve hired recovering addicts. They want their farm to be a place where everyone feels welcome, she said.

Two of their employees are on the autism spectrum. They have driver’s licenses and spray licenses. Their personalities are very different, however, and they need to be managed differently. One can be told to trim trees until lunchtime, while the other needs frequent check-ins, Danielle said.

Frank Teeple recommended matching the worker’s skill set with the right job. Some people on the spectrum work better in an office. Some like to sticker bags in the packing house. Some can trim trees all day. Fortunately, fruit farms can offer all of these roles, and more, and the kind of environment where autistic employees can thrive.

“You don’t have to interact with anybody or be somebody society wants you to be,” Danielle said. “It’s just you and the trees. It’s kind of a beautiful thing.”

What a wonderful story about a great family of growers. I’ve had the privilege and pleasure of working with several generations of Teeples and their kindness and skill set has transferred across the generations. Such attributes influenced my choice for a research career. The apple industry is amazing!