Measuring the ratio of nitrogen to calcium in Honeycrisp peels provides a key step in predicting whether apples will develop bitter bit in storage. (Photo illustration by TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

Penn State University scientists have created a model growers can use to better predict which Honeycrisp blocks will likely develop bitter pit in storage so they can make better sales decisions several weeks before harvest.

Bitter pit in Honeycrisp is a complex problem that is influenced by many factors, including: crop load; growing season conditions; maturity at harvest; postharvest practices; and the levels of key nutrients and minerals, such as calcium, in the fruit.

Penn State horticulturalist Rich Marini cautions that the new tool assesses just a few of these factors while the fruit is on the trees and, although it offers good information, it doesn’t give a complete picture of the fruit’s predisposition to the disorder.

“Even though it’s a pretty good model, it only explains a little over 60 percent of the variation” in bitter pit incidence, Marini said. The model evaluates a tree’s vigor — assessed by shoot length measurements — and the nutrient content of fruit peels to determine the fruit’s likelihood of developing bitter pit.

Marini explained that he and his colleagues collected data in six Honeycrisp orchards over three years on crop load, shoot length, and the levels of calcium, potassium, phosphorus, magnesium and nitrogen in the fruit peels, along with the rates of bitter pit after cold storage. Then, they used a statistical analysis to figure out which factors were most strongly linked to bitter pit. The results were a bit unexpected.

“In the past, I’ve always thought that it was the ratio of potassium and magnesium to calcium (that matters). But it turns out that is a pretty good indication, but the nitrogen to calcium actually gives us the best,” he said. “I think we’re the first ones that were able to identify that tree vigor seems to be important as well.”

It’s not that surprising, because vigor is related to crop load, as lightly cropped trees tend to have more vigorous growth. But, Marini said it’s still not clear why shoot length and the nitrogen-to-calcium ratios are better predictors of the disorder than crop load or other nutrient levels.

To use the model, growers should select 20 trees per block, measure the length of five typical terminal shoots and calculate an average length.

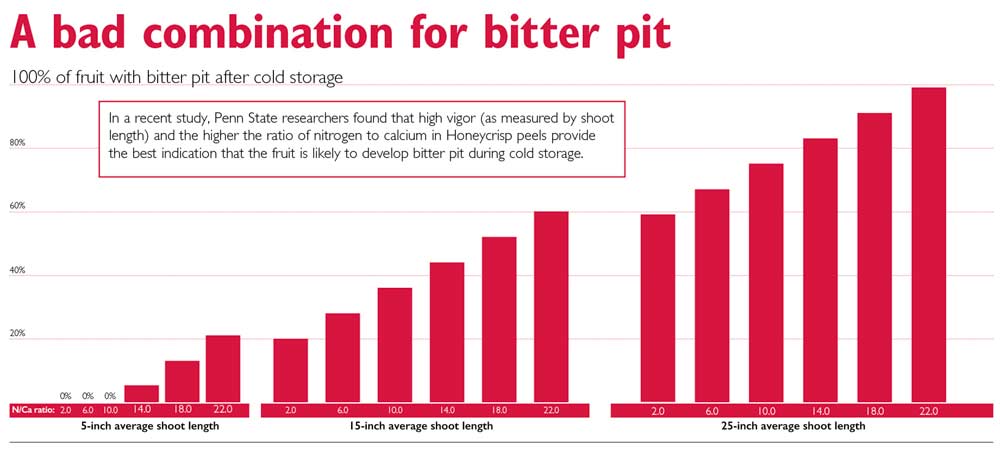

CLICK TO ENLARGE — In a recent study, Penn State researchers found that high vigor (as measured by shoot length) and the higher the ratio of nitrogen to calcium in Honeycrisp peels provide the best indication that the fruit is likely to develop bitter pit during cold storage. Source: Penn State University (Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower)

Growers should also pick three apples from the same 20 trees about three weeks before harvest and peel the apples with a potato peel, avoiding the flesh or scraping it off the peel with a knife, Marini said. Then, combine the peels and dry them overnight in an oven at 180 degrees. A cookie sheet and parchment paper are recommended for this step.

The peel sample can be submitted to the Penn State Agricultural Analytical Services Lab with a standard analysis kit, which is available from Penn State Extension county offices for a fee of $24. Labs in other regions should be able to perform the same analysis, as long as they are told in advance that the samples are peel tissue, Marini said.

“We’re hoping we can tell them the likelihood that these apples will develop a lot of bitter pit so that they can decide how to market them,” Marini said.

The model should work well for growers across the Northeast, but the growing conditions in the Pacific Northwest are different enough that the research should probably be replicated before growers rely on it, he said.

Across the country, many questions about bitter pit remain, such as the role of temperature from fruit position and growing climate.

“This year in Pennsylvania, it’s been cool and wet so we are expecting less bitter pit. Last year we had a hot, dry summer, and it was by far the worst for bitter pit we’ve had,” Marini said. “And one thing that still troubles me is that we have a lot of trees with no bitter pit, which is great, but I can’t figure out why. There are factors that we haven’t identified yet. This is just a step and we’re making progress.” •

– by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment