—story by Kate Prengaman

—photos by TJ Mullinax

—graphic by Jared Johnson

On a new cultivar’s journey from discovery to nursery, a clean plant center serves as a vital pit stop, ensuring that the propagative material is disease-free and gives growers the best start with their new stock.

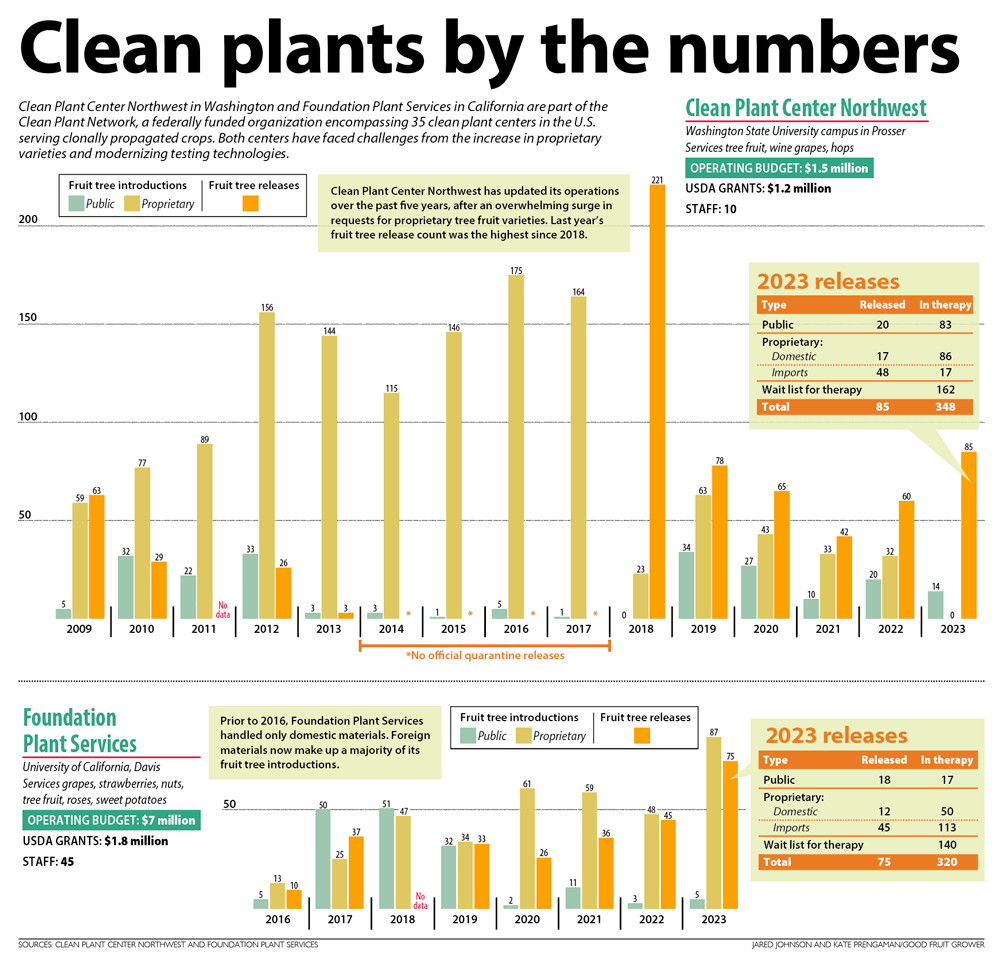

Over the past decade, that pit stop became a detour at the Clean Plant Center Northwest, located on the Washington State University campus in Prosser, as the boom in tree fruit varieties, most of them proprietary, overwhelmed its resources. From 2012 to 2016, nurseries submitted 736 proprietary varieties, and the resulting delays drove some nurseries to take their material elsewhere.

No matter where a cultivar is sent for cleanup, costs are rising and technology is changing, creating new challenges as the nursery industry and the growers they supply face widespread downturns. And as the Clean Plant Center Northwest (CPCNW) continues work to modernize its operations and alleviate its backlog, some tree fruit nurseries are pulling back instead of applauding. Industry representatives who spoke with Good Fruit Grower cite better service and lower fees at their chosen alternatives.

They also share a lingering frustration over the sense that costs are increasing even as they aren’t always getting what they paid for.

“There’s no guarantee they will make progress,” said Jim Adams of Willow Drive Nursery.

Director Scott Harper, who joined CPCNW in 2017, said the center has made significant strides over the past five years and released more fruit trees in that period than the preceding 20 years, including 85 in 2023 alone.

“We’ve done a lot of good work over the past few years fixing the center and making it work,” said Harper. “We’ve been focused on the core mission of getting plants out. The program is working pretty well, even if the changes might not be to everyone’s liking.”

Still, the wild card of biology complicates the process. Even with modern technology, some cultivars are easy to clean up — and others very difficult.

The proprietary pull

Clean Plant Center Northwest is part of the federally funded National Clean Plant Network, which has 35 centers around the U.S. serving clonally propagated crops, from roses and tree fruit to berries, grapes and hops. The Prosser center handles tree fruit, wine grapes and hops, while the larger Foundation Plant Services at University of California, Davis, handles grapes, strawberries, roses, sweet potatoes, nuts and, increasingly, tree fruit, as more growers turned to FPS amid the Prosser center’s backlog. (Clemson University hosts a stone-fruit-focused center as well.)

Each center also protects hundreds of clean cultivars in foundations and sells material to propagators.

Tree fruit variety development is a global game, but the definition of a clean plant varies by region, as do quarantine standards. The U.S., for instance, requires new cultivars to be free of some viruses that are commonplace and accepted in Europe.

“The weight of the world was on Prosser to eliminate stuff nobody else cared about,” said Dale Goldy, owner of Gold Crown Nursery. “I tell people to get material cleaned up before you send it over, or it’s going to get in a very long line.”

That line is now shrinking. Over the past six years, CPCNW fully released 534 tree fruit cultivars, along with 17 conditional releases for cultivars harboring cherry virus A, which is not considered a risk. During that time, it received 272 new introductions, down from the 2012 peak of 189 in a single year.

Meanwhile, FPS has released 232 tree fruit cultivars over the past five years, as it built capacity for that industry, and received 342 new introductions, 84 percent of them proprietary.

The increasing cost of cleanup, due in part to new DNA technology raises questions about who should pay for these centers’ industry-supporting work. Should it be taxpayers? Variety developers? Should growers pay through an assessment on the resulting plants?

Federal funding for these programs has not kept pace with inflation or demand for new tree fruit cultivars, forcing the centers to seek industry support and raise user fees to continue operations.

“Clean plant centers have to be fiscally sustainable,” said Cliff Beumel, president of Agromillora California Nursery, part of a global nursery business. “FPS hits that mark. They are good at having a funding structure, so the industry pays for around 70 percent of the operation.”

The California Department of Agriculture places a 1 percent assessment on all fruit tree, nut and grapevine nursery stock to support FPS, along with disease testing and research grants. But, with tree and vine orders declining, this funding is shrinking, Beumel said.

At CPCNW, federal U.S. Department of Agriculture grant dollars cover most but not all of its $1.5 million operating budget. So, to make up the gap, the center recently raised service fees on proprietary varieties. (The 2023 grant was $1.2 million, about half for tree fruit and half for grapes and hops.)

“We feel, as an institution, we should be spending public money for public good, not for proprietary gain,” Harper said.

New fee structures reflect that. Work on public cultivars is free, fully supported by federal dollars. Sponsors of proprietary trees, grapes and hops will now be charged more for intake testing ($2,500), each round of cleanup therapy ($2,000), and retention in the center’s protected greenhouse foundation blocks ($500 per year). For sponsors who want their varieties to be protected as trade secrets and not appear in public records, WSU will now charge $2,000 a year for foundation retention, to cover the liability it perceives.

User fees are still subsidized by the USDA for cultivars sponsored by U.S. companies, Harper said, and fees for foreign companies are higher. Prices for clean budwood did not change.

FPS updated its tree fruit prices in 2023 as well, increasing fees on proprietary material to $4,500, though it remains a one-time fee for testing and any needed therapy — so while the cost of one round of testing and therapy at the Northwest center is comparable to FPS, additional rounds could add up.

FPS also charges for public material introductions — at $2,500 a pop.

“We charge for all our services, because we are a service center,” said director Maher Al Rwahnih, adding that his main source of funding for tree fruit is the network’s federal grant ($1.8 million in 2023 across multiple crops) which has not kept pace with FPS’ increase in tree fruit introductions in recent years.

Raising prices prevents people from bringing in “everything under the sun” and clogging the pipeline, said Beumel, whose nursery sponsors proprietary introductions, albeit primarily olives at the moment. “If it’s worth it, it’s worth millions. Let’s let the capital market reign here,” he said.

Higher fees for proprietary material help centers strike a balance between public and private material and keep operations on firmer financial footing.

“The center can’t make sense and benefit the industry as a whole if it doesn’t serve the needs of the proprietary material that is flowing around the world,” Beumel said.

FPS growing its tree fruit services

Fifteen years ago, few in the tree fruit industry used FPS, said Beumel, who was part of the push for FPS to start doing so. “Now, they are a victim of their own success.”

Director Al Rwahnih said that although the center is known for grapes, tree fruit introductions have grown to a similar scale in recent years — especially stone fruit, but apples as well. Most of the introductions today are proprietary varieties, the majority from international origin, he said.

Taking on more tree fruit required investing in developing meristem tissue culture technology, Al Rwahnih said. FPS recently brought on a tissue culture expert as a consultant, which is already improving the center’s processes, he said.

Pacific Northwest tree fruit nursery owners who increasingly brought material to FPS in recent years said they’ve been pleased with the service.

Al Rwahnih credits the center’s investment in database management, communication, DNA testing for plant identification and a more efficient approach to intake testing as reasons why his stakeholders express such wide support.

“We consult the industry and make them part of the decision — as good customer service, we consult with them and explain the problem and proposed solution so there are no surprises,” he said.

The grape industry pays assessments on all clean vines the nurseries produce as a result of FPS work, and a similar assessment of cherry trees is in the works.

The grape industry also supported FPS to build a greenhouse to protect foundation plants from insect-vectored diseases, after an outdoor foundation was found to be infected with red blotch. Tree fruit foundations are all outside, and regularly tested, but Al Rwahnih said FPS hopes to build a similar “backup” for tree fruit.

A new era at Clean Plant Center Northwest

Harper said he’s proud of the work his small team has done to right the ship at CPCNW. The fee structure should better cover operating costs and improve transparency on the costs of the services it provides. This summer, the center will launch a new, long-awaited customer management platform and database to improve communication with the industry. And a partnership with the Washington State Department of Agriculture makes export services possible again.

“I don’t think people realize how much more efficient things are than they have been,” said Scot Hulbert, senior associate dean of WSU’s College of Agricultural, Human, and Natural Resource Sciences. “Some nurseries are opposed to price increases, but we can’t do it cheaper. (The center) is under a statutory obligation to cover all their costs.”

The center has a staff of 10, plus Harper, who also has a role as a research plant pathologist.

Generating more industry financial support has been a topic for years. Recently, the hop and grape industries have increased their support of the center through voluntary assessments, Hulbert said, similar to FPS’ grape assessment.

Tree fruit nurseries, frustrated with changes in recent years, have not increased their support. Concerns include delays, fees and a perceived lack of communication.

“We have material there from 2014 still not released,” said Kevin Brandt of Brandt’s Fruit Trees. He is frustrated that CPCNW now wants an additional fee for another round of therapy when his initial contract was “for the cleaning of a plant,” he said.

Harper said the center can’t afford to put those materials through round after round of therapy and testing with the fees (which ranged from $1,200 to $2,000 for testing and $1,500 to $2,000 for therapy) long ago spent.

“I think the record is (four) attempts on something, costing time and money and space someone else’s plant could have,” Harper said. “Now it’s up to stakeholders to decide if they want to keep going.”

Brandt pulled his material earlier this year. As a nursery that brings in dozens of varieties from global partners for trials, the new fees quickly add up, Brandt said. For the price, taking material to labs in France or the Netherlands with better service is preferable. Then he can import material through the USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service center in Beltsville, Maryland, which offers free testing but no therapy. If the material tests clean, twice, it is released to him; if not, it must be destroyed.

In addition to the fees, nurseries were frustrated that CPCNW stopped helping them export clean selections last year, Brandt said.

“Prosser was established to help facilitate worldwide distribution,” he said.

Harper said that facilitating exports — including researching requirements in each market, sample testing and paperwork preparation — was taxing the center’s limited resources and not supported by its federal funds. However, under a new partnership with the Washington State Department of Agriculture’s plant protection program, export services became available again this year.

“The new process basically streamlines the request for export certificates with the other commodities we certify,” said Benita Matheson, field operations manager for the WSDA plant services program.

WSU sees this as another success on the path to stabilizing the center while serving its U.S. stakeholders.

“We prioritize the mission to clean plants for the industry in a manner that we are serving the most people we can,” Hulbert said. “It’s not a high priority to get someone’s variety to another country, and we can’t legally subsidize it.”

Grape and hop support

Clean Plant Center Northwest handles material for the tree fruit, grape and hop industries, and in the past few years, grape and hop nurseries have contributed over $250,000 to the center through donations and by adding a small, pass-through fee for each plant propagated from clean material.

“Our industry understands the value and impact of planting clean, certified plants, so we had to do it,” said Vicky Scharlau, former executive director of the Washington Winegrowers Association, who worked closely on these issues. Aligning with the approach at Foundation Plant Services, which also handles grapes, just made sense.

The added fee, voluntarily applied by nurseries, raised no concern from grape and hop customers, said Cameron Fox, who was growing operations manager at Skagit Horticulture, a commercial nursery that shut down in April. He now works with Qualterra.

“I never had pushback on that,” he said of the assessment.

The center’s records show it released 33 grapes and 30 hops in the past five years. The grape industry largely relies on public materials, Scharlau said.

In the era of shrinking public funding, the center needs support from all three crops to maintain the scale required to operate, she said.

“At some point, tree fruit and grapes and hops truly need to decide, is this important here or not?” she said. “So, what can we do to get it to survive and thrive? (The center) has been in survival mode for a long time.”

New technology detects more pathogens, but also raises costs

The new requirement for a high-throughput sequencing approach to testing, which the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service enacted in 2021, is detecting more pathogens and raising costs, according to the directors of the Clean Plant Center Northwest in Washington and Foundation Plant Services in California.

Instead of running tests that look for specific known pathogens, this approach detects known and unknown viral agents. APHIS requires two such tests, in two growing seasons, to confirm a clean bill of health.

FPS data show that from 2015 to 2019, about 40 percent of tree fruit introductions tested negative. Now, it’s less than 10 percent. At CPCNW, director Scott Harper estimated it to be less than 20 percent now.

“We are catching the known pathogens at higher frequencies,” Harper said.

For rare clean selections, the process can save time, because centers no longer have to grow trees for several years to watch for symptoms. But requiring two of these DNA tests increases costs.

At FPS, director Maher Al Rwahnih added an additional test to increase efficiency. He does an “introductory” DNA test to quickly inform variety sponsors if their material is infected. If it is, they can go straight to the therapy process, skipping the yearlong regulatory test that was doomed to fail, or try again.

“This gives you a chance to replace the material with a cleaner source right away,” he said.

CPCNW can’t offer this step because it can’t afford its own DNA sequencing equipment, Harper said. He sends samples to a different Washington State University lab, which has a longer turnaround time, so by the time he gets results, the samples are propagated and nearing time for the second round of testing.

The new technology has also uncovered some unfortunate surprises. For example, in 2021, Harper’s team discovered that a few apple viruses can be transmitted by seed. Scientists previously believed no seed transmission was possible, so, for decades, seedling rootstocks were seen as the safest choice for the clean plant process. The discovery should improve apple cleanup processes, but all apple selections had to be restarted once a clean, clonally produced rootstock source was secured.

As for finding novel DNA with unknown disease status? Yes, they do find some of what Al Rwahnih calls “background” viral agents, and APHIS is seeking ways to delist those that can be proven of no consequence, he said.

In the meantime, both centers must clean those, too, though Harper pointed out that they almost always occur with other primary pathogens that would require cleanup anyway.

Some nurseries would like to see APHIS ease the regulations on so-called latent viruses, making it easier to do conditional releases and speed up the introduction process.

That’s outside the purview of the clean plant centers themselves, and Harper urged caution about embracing the idea that the quickest way to clean up a plant is to lower the standards.

“These programs exist for a reason. They were started to protect growers from the known and nasty pathogens as well as the unknowns, because we don’t want them to find out the hard way that something is dangerous,” Harper said. “The problem is that’s not appreciated until there is a problem.”

—K. Prengaman

Leave A Comment