Some Michigan fruit regions are better known than others. There’s the Ridge just north of Grand Rapids, home to most of the state’s apples. There’s Northwest Michigan, home to most of the state’s tart cherries. There’s Southwest Michigan, home to much of the state’s blueberries, grapes and peaches.

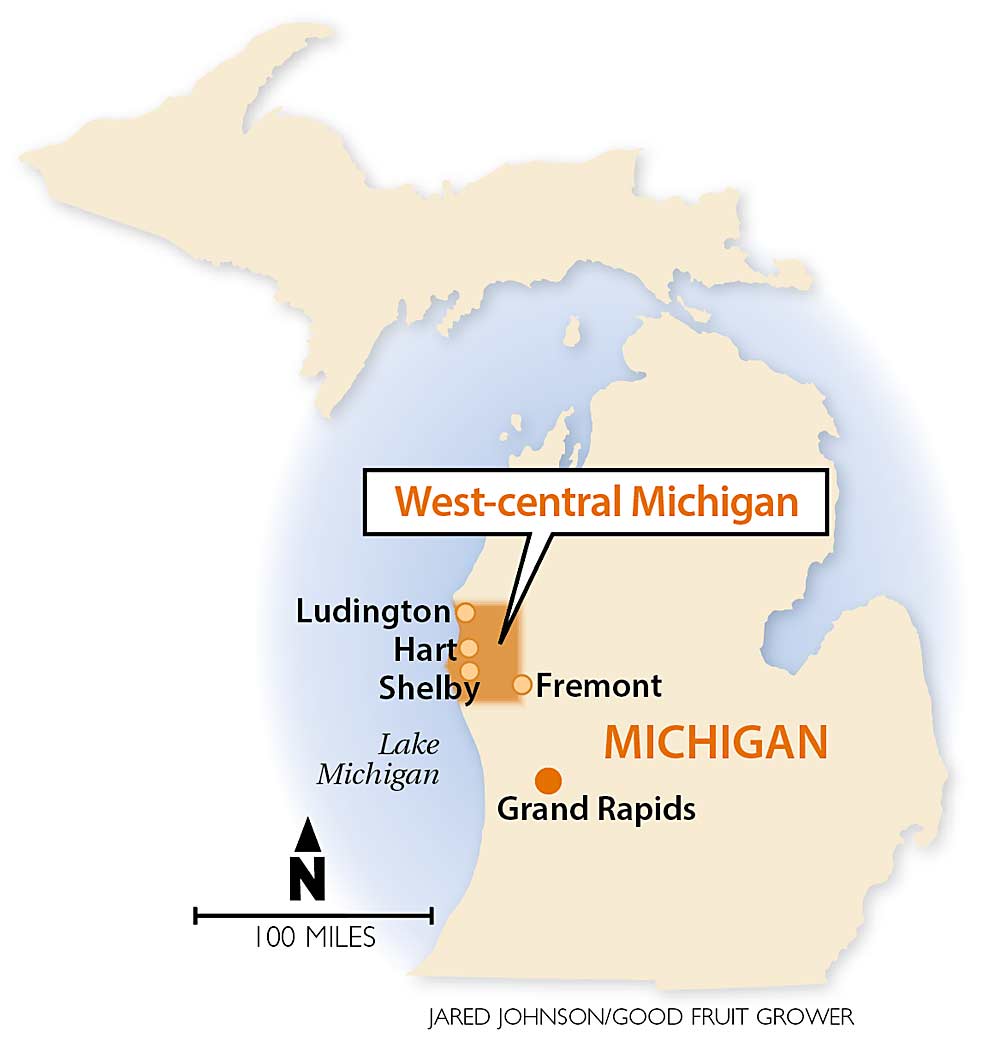

But there’s another region, not as well known, that might grow a greater variety of fruit than any of the others. It’s often lumped in with the Ridge, being about an hour-and-a-half drive northwest of Grand Rapids. But Michigan State University Extension treats West-central Michigan separately — as a region with its own unique climate and soil, and one that houses a fruit industry with its own particular history and characteristics. It’s also a region that’s changing with the times, as growers there plant more fresh-market apples to replace some of their processing crops, said David Jones, the local tree fruit extension educator.

The under-the-radar region got the spotlight treatment when the International Fruit Tree Association visited in February, following its 63rd annual conference in Grand Rapids. Jones served as the main guide on the post-conference tour, explaining to growers from across North America what makes his region so distinct from the Ridge.

For one thing, the region’s close proximity to Lake Michigan gives it sandier soils and a more temperate climate than the Ridge. For another, the region is home to a handful of major fruit processors, and most of its fruit is grown specifically for processing markets, Jones said.

The region’s emphasis on processing, and the lack of research specifically tailored to its soil and climate, have contributed to West-central Michigan being “a little bit behind the times,” as local grower David Rennhack described it. Local growers have not had to be as cutting-edge as growers in other regions, but that’s starting to change. The region has a lot of untapped potential, which makes it “the hidden gem in Michigan,” he said.

Tapping into that potential is what spurred the region’s growers to fundraise and partner with MSU to build a new research station in Hart, Michigan, this year. (See: New research station underway in West-central Michigan.)

One of the region’s strengths is crop diversity. There are about 11,000 acres of tart cherries, between 3,000 and 5,000 acres of apples, 800 or 900 acres of peaches, 400 acres of Bartlett pears, fewer than 100 acres of grapes and a small but growing amount of sweet cherries, Jones said. The vast majority of that fruit is grown for the region’s four major processors: Peterson Farms, Indian Summer Co-Op, Seneca Foods and Gerber/Nestle. But it’s the newer plantings that feature high-density systems of more profitable fresh-market apples such as EverCrisp, Honeycrisp and Gala.

Jones estimated there are 75 to 100 fruit farms in West-central Michigan, most of them clustered in a long, skinny line along the eastern shore of Lake Michigan. The counties of Mason and Oceana make up most of the growing region, along with parts of Newaygo County. Hart, where Jones’ MSU office sits, lies roughly in the geographic center of the fruit region, though the unofficial dividing line between West-central Michigan and the Ridge sits around Fremont, a town about 20 miles inland from the lake.

Many of the region’s fruit growers also grow asparagus, fitting since the area represents one of the largest asparagus production regions in the United States. Other traditional crops include Christmas trees and maple syrup, but both are less common than they used to be, he said.

Spotlight on the future

A major shift in the region’s fortunes came with the hiring of Jones in 2017. The position of regional extension educator had been vacant for a few years, and Jones brought a renewed vigor and focus to the specific research needs of the region, according to growers interviewed for this story. The new research center also will expand MSU’s capacity to serve West-central Michigan.

The emphasis on fresh apples marked another major shift. Most apples grown in the region are still processed, but the youngest plantings are all modern, high-density blocks with varieties grown for the fresh market. Those new blocks are now being grown on the prime growing sites — usually hilltops to protect from frost — that used to be reserved for peaches and cherries. Apples were planted on the poorest sites in the past, Jones said.

“Apples have gone from being a bulk processing crop to being the tenderloin on most farms in terms of value per acre,” he said.

At Rennhack Orchards, Rennhack showed IFTA attendees 2-year-old and 5-year-old plantings of EverCrisp on Geneva rootstocks. He said he was looking for a later-season apple, one he could store until the following summer, and EverCrisp fit the bill. It’s now one of the most popular varieties at his farm market.

“Just out of the cooler, they’re good and crunchy,” he said. “People are happy to have a local-grown piece of fruit in June and July.”

Rennhack’s farm market in Hart gives him a fairly unique sales outlet for the area. The local customer base might be small, but it’s very loyal, and there’s a surge of tourism traffic in the summer. He grows a wide assortment of vegetables and fruits for the market, including 10 acres of sweet cherries, 5 acres of peaches, and a smattering of nectarines, plums, apricots and table grapes. He only has 24 tart cherry trees left, all handpicked for the market. He got out of bulk tart cherries in 2013.

“I didn’t see a positive future for the processed tart market, so I decided to get out and get heavier into apples,” he said.

He has about 95 acres of apples now, most of them sold fresh. He said fresh has greater profit potential than processing, though even fresh prices haven’t been great the past couple of years. He’ll plant a few more EverCrisp trees within the next year, then he plans to hold off on new plantings for a while.

At Riley Orchards, Mark Riley and his son, Andy, showed IFTA visitors blocks of Wildfire Gala and Premier Honeycrisp. They chose Wildfire Gala, in part, to give their workers an early variety to pick. They’ll plant EverCrisp soon, to add a late variety.

Between the apples, cherries, peaches, asparagus and other crops they grow, the Rileys keep themselves busy. The other crops take away time they could devote to their apples, but the diversity fits Andy’s philosophy, he said: “If you’re not harvesting, you’re spending money. We try to always be harvesting something.”

At Van Agtmael Orchards, a few miles inland from Hart, Mike Van Agtmael showed IFTA tourgoers a few blocks of high-density apples, including Honeycrisp. He’s been growing Honeycrisp since 1998, with each new block planted tighter and tighter. He still grows hundreds of acres of tart cherries and asparagus, as his father did, but modern growing techniques and high-density apples keep his farm competitive.

“What we do today is not good enough for tomorrow,” he told the IFTA audience. “We have to keep getting better.”

Fresh-market potential

Further east, about 20 to 30 miles inland from Lake Michigan, near Fremont, grower and packer Eric Roossinck showed IFTA visitors his blocks of high-density Honeycrisp, Aztec Fuji and the club variety Smitten. He’s been modernizing his variety mix for years now, and Gala, Fuji and Honeycrisp now make up two-thirds of his apple crop.

Roossinck grows 300 acres of fruit on farmland straddling the Ridge and West-central Michigan; his packing shed handles apples from both regions. Roossinck said his soil is heavier, more like soil on the Ridge, and not as sandy as the farms nearer the lake.

“I often tell people we’re at the end of the Ridge line,” he said.

It’s not just local growers who see the potential of fresh apples in West-central Michigan. Growers from the Ridge are buying farmland to plant more apples in the region, too, seeking better coloring for their fruit and more reasonable land prices. Suburban sprawl, creeping north from Grand Rapids, is gobbling up farmland in the southern parts of the Ridge and driving up land prices throughout that region. Cheaper farmland prices can be found in West-central Michigan, and the region’s crisp autumn nights can give apples a nice red color, Jones said.

The attention his region is getting from other parts of the state, combined with its traditional emphasis on processing fruit, make for a bright future for West-central Michigan’s fruit growers, said Andy Riley.

“We can grow everything (other regions) can grow, plus asparagus and everything else,” he said. “That’s why I think this is the best growing region in the state.”

One of the things that’s given the region its strength and longevity, even in bad economic times, is that level of crop diversity, Jones said.

“Tart cherries are about as tough as they can be right now, but other commodities have been reasonably profitable,” he said. “The farms here will endure.”

—by Matt Milkovich

Related:

—New research station underway in West-central Michigan

Leave A Comment