Longtime employee Bill Cawley, 78, moves bins and pallets on March, 30, 2016, at the Del Monte Foods processing facility in Yakima, Washington. at the Del Monte Foods processing facility in Yakima, Washington. The Yakima plant, recognizable from a distance by the green water tower at right, is celebrating 100 years under the Del Monte name. Cawley has worked there for 48 years. (Ross Courtney/Good Fruit Grower)

For 100 years, Del Monte Foods has operated the fruit processing plant at 108 Walnut Street in Yakima, Washington. Bill Cawley has worked there nearly half that time.

Cawley, 78, has held jobs as cook room laborer, bin repairer, greaser and now forklift driver, stacking and restacking 120,000 bins in the seemingly infinite bin yard.

“They treat you nice,” said the 48-year employee.

Cawley, dozens of fellow employees, suppliers and about 200 growers will gather May 11 to celebrate the centennial anniversary of the Del Monte name on the Yakima plant, the biggest pear processor in the nation.

David Withycombe, chief operations officer at the processing giant’s Walnut Creek, California, headquarters may attend, said Mike Fuerst, the company’s director of fruit operations.

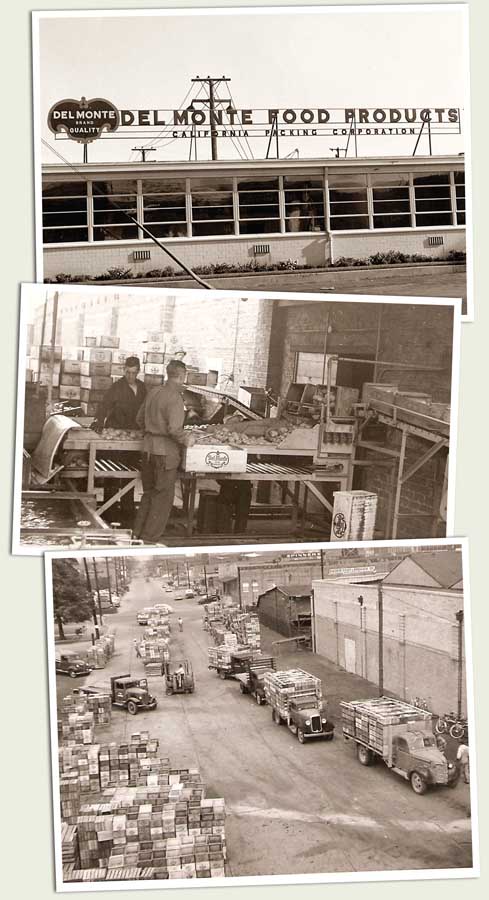

The top photo, from 1951, shows the sign above the Del Monte Foods office at the Yakima, Washington, processing facility. The office, with the same windows, is still there today. The center photo, taken around 1950, shows workers dumping peaches by hand. At bottom, trucks line up to deliver peaches in 1948. (Historical photos Courtesy Del Monte Foods)

Del Monte, the company, started in 1886 in San Francisco. The Walnut Street facility was built in the early 1900s as an apple dehydrator.

The two married in 1916 as part of the merger that formed the California Packing Corporation, of which Del Monte became the primary brand.

Since then, Del Monte has grown to process 60,000 tons of pears per year, about half the Northwest’s total, and employ 600 people during pear season from August to November.

Del Monte’s Yakima plant is the largest pear processor in the United States and most likely the world, said Jay Grandy, the recently retired longtime manager of the Washington-Oregon Canning Pear Association. The facility also cans some cherries and apples.

Overall, the company has 7,800 employees and generated $1.7 billion in net sales in 2015.

However, longtime growers who sell fruit to Del Monte claim the corporation’s size doesn’t get in the way of relationships and common-sense deals.

“Tolerant and flexible,” they were called by third-generation Del Monte grower and shipper Gary Wells in Hood River, Oregon.

For example, Del Monte allows the Wells family orchard company, Viewmont Orchards, to use Del Monte bins for apple harvest in exchange for storing them.

“They actually listen to growers,” said Chris Morton, a third-generation Del Monte grower in the Yakima area.

Morton, who also grows apples, cherries and stone fruit, considers his contracts with Del Monte among the safest, surest portions of his business.

Prices are negotiated with the Washington-Oregon Canning Pear Association and the firm pays growers half their returns within 30 days of harvest and the rest usually within 60 days with few price adjustments, Morton said.

Morton and Wells are members of the Yakima-based association, which represents growers in contract price negotiations.

Industry consolidation over the past 10 years has left only three pear canners in the Northwest, all in Washington — Del Monte, Seneca Foods Corp. in Sunnyside and the Neil Jones Food Co. in Vancouver.

The association also negotiates contracts with Del Monte and Jones; the price is $340 per ton this year and will rise to $360 per ton in 2017.

The industry has changed drastically in the past 100 years, employees said. Things previously done by hand — dumping bins, peeling and coring pears — are now handled by machines, allowing capacity to soar.

“The plant, it’s so different than when I first started,” said Paulette Fahnestock, who has worked at the Yakima facility since 1975 with only a four-year break in the early 1980s. “When I first started it was like the Dark Ages.”

The self-described Jill-of-all-trades plans to retire in a little more than a year. Del Monte and the industry face challenges.

Consumer preference has swung toward fresh fruits and vegetables instead of canned, while modern transportation and storage methods have made more high-quality fresh fruits available in stores year-round.

In the early 1990s, nearly 75 percent of Northwest Bartlett pears — the most common canning variety — were canned. Today, fresh and canned have roughly a 50-50 split while new varieties go only to the fresh market.

The canners collectively sell 5 percent to 10 percent of their canned pears to the U.S. Department of Agriculture for distribution to schools, prisons and the military, Fuerst said. •

– by Ross Courtney

This story has been updated to reflect the following correction:

A story in the May 1 issue on the 100th anniversary of the Del Monte processing plant in Yakima, Washington, contained two inaccurate figures. The plant processes about 60,000 tons of pears per year, and growers are paid a negotiated price of $340 per ton this year and $360 per ton in 2017. Good Fruit Grower regrets the errors.

Leave A Comment