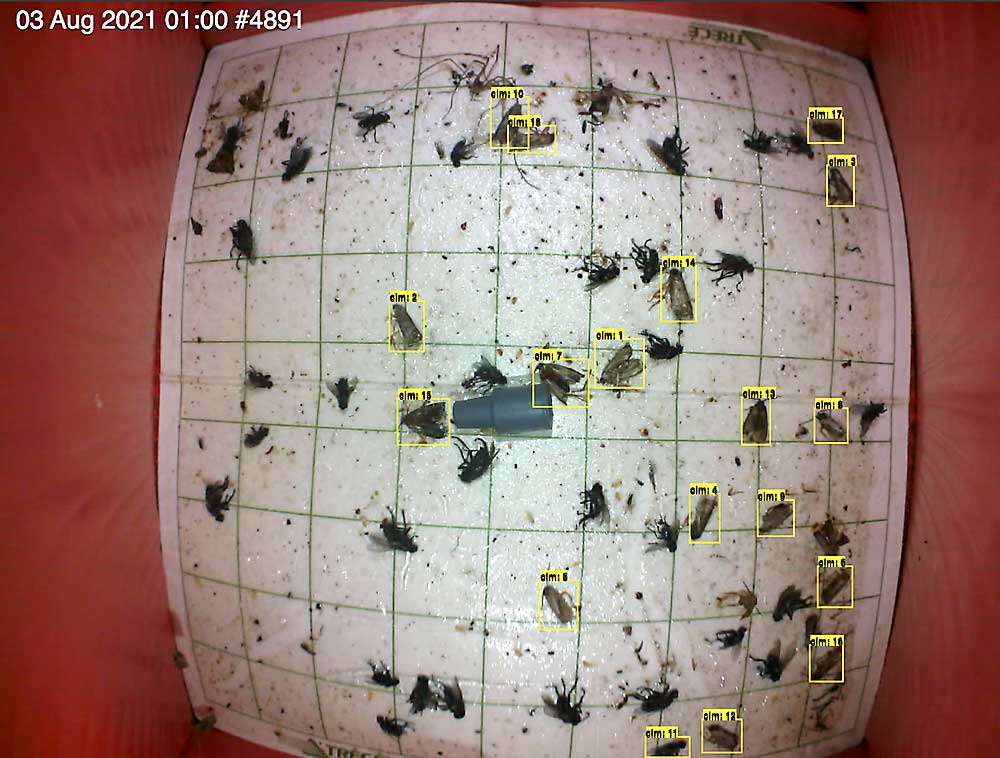

The combination of increasingly affordable technology and improved artificial intelligence has led to a rise in automated camera traps for growers considering new precision pest control tools.

Camera traps allow users to check pest pressure over hundreds of acres from a computer, as often as needed, instead of driving through row after row to check by hand maybe once a week, while artificial intelligence recognizes key insects and alerts growers when target bugs are caught.

Camera traps are an important tool for the future in the management of many pests, including codling moth, especially since market trends have the industry shifting toward organic methods, said Chris Adams, an Oregon State University assistant professor of tree fruit entomology and chair of the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission codling moth task force.

“What we have left is to make smarter and more timely decisions, and I think camera traps help us do that,” Adams said.

Adams has trials underway with two camera trap vendors, Semios and Trapview.

The traps themselves catch insects on old-fashioned sticky paper, and an internal camera uploads one or more photos in the wee hours of each morning. But the traps are provided as part of a service plan that includes data from the traps, artificial intelligence to identify pests, miniature weather stations and pheromone emitters, all connected remotely. Vendors typically have a team of entomologists to monitor and provide quality control for the artificial intelligence.

Three examples

Good Fruit Grower interviewed representatives from Semios and CropVue Technologies, both based in Vancouver, British Columbia, and Trapview, a Slovenia-based company with North American offices in Vancouver, Washington. Other examples include Isagro of Italy, Adama of Israel, FarmSense of the United Kingdom, DTN of Minnesota and Pessl Instruments of Austria.

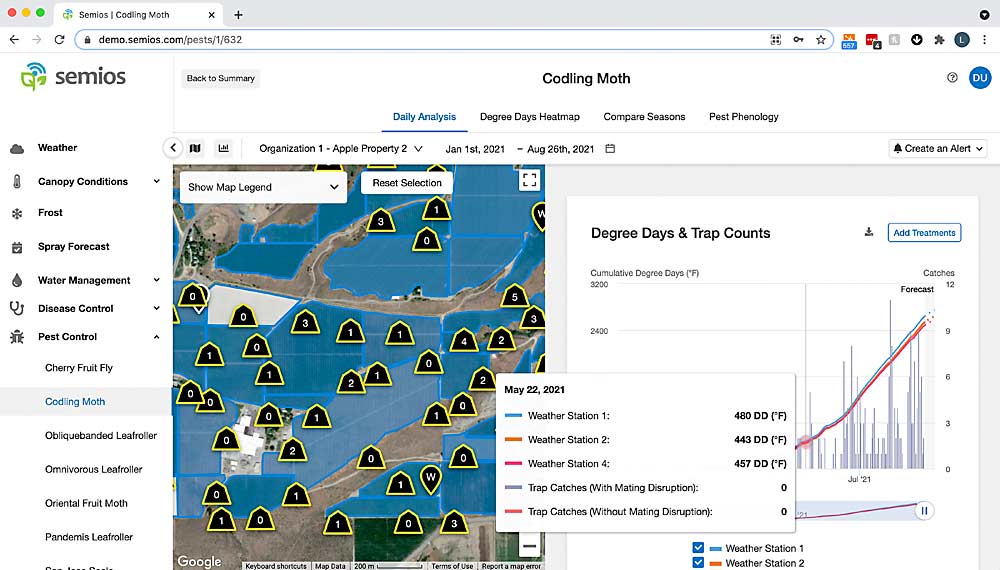

Semios has about 10,000 camera traps in specialty crops throughout the world, working with tree fruit growers since 2015, said James Watson, director of sales and marketing.

Trapview has thousands of clients in specialty crops globally but has been operating in the United States only since 2018, said Jorge Pacheco, the North American managing director. So far, the company has more presence in California vegetables than Northwest tree fruit.

CropVue Technologies entered the arena in 2019. The company currently supports about 5,000 acres with a few Washington pilot growers but is poised for a full commercial launch next year, said Terry Arden, CEO.

All three use similar technology but different business models.

Semios directly works with and sells to growers. Its software acts as a one-stop shop, which will allow growers to pull data from companies Semios acquired over the summer, including the company that owns the ApRecs online spray recommendation writing tool. The company hangs the traps, replenishes liners, installs the tools, remotely monitors the functions and maintains all equipment.

Trapview and CropVue distribute through suppliers and management companies such as Wilbur-Ellis, G.S. Long or Chamberlin Agriculture.

“They have a direct connection with those growers with other inputs, not just pest monitoring,” said Pacheco of Trapview.

CropVue’s Arden agreed. “The distributors have long-term relationships with growers,” he said.

The trap companies also differ in connectivity. Hinging their future on the build-out of cellular IoT (Internet of Things) service, CropVue and Trapview install a network in which each device independently uploads data to the cloud.

Semios, which built its infrastructure before IoT, relies on a “meshed network” with repeaters that talk to a gateway, which in turn uploads bigger lumps of data to its cloud. However, the company has already deployed IoT in some spots.

Costs

Semios and Trapview declined to discuss pricing because each orchard requires a unique level of service. Trapview is still in the process of setting its subscription rates.

CropVue is shooting for roughly $25 per acre per year, assuming one trap and one canopy weather node for every 10 acres, but that’s flexible. Washington State University researchers recommend a ratio of one trap per 2.5 acres for codling moth. Other entomologists’ suggestions range from one to five.

Sold individually, traps run $400 to $1,000 per season per trap, enough to be a barrier to entry, said Pete McGhee, research and development coordinator for Pacific Biocontrol Corp. in Corvallis, Oregon, and a former Michigan State University researcher who has worked with camera traps.

But the price will come down and the technology will continue to improve in all the cameras. Resolution is getting sharper, artificial intelligence is getting better at recognizing species and processing power continues to increase, McGhee said.

The main benefit to the camera traps and surrounding services is recognizing the threshold early in the season for “setting the biofix,” McGhee said — triggering the phenology model that will give predictive advice for when to spray.

After that, growers or consultants can monitor progress.

His concern is that many of the vendors have not publicly validated their approaches against the growing degree-day models and thresholds based on 30 years of university research.

All three companies in this story say they have run trials with university researchers. Meanwhile, in addition to running trusted models, their own vast datasets and artificial intelligence can refine the models and apply them uniquely to each orchard and its microclimate.

“They are changing the way decisions are made,” said Watson of Semios.

One grower’s take

Teah Smith, entomologist and agricultural consultant for Zirkle Fruit, is a fan of camera traps. The company is based in Yakima, Washington, though she is based in the Wenatchee area.

Smith is responsible for steering pest control over 6,500 acres of orchards. She used to send her team of scouts to check traps every week. Camera traps save them time for other things, she said.

She first experimented with Semios camera traps in 2015 on two 100-acre orchards. She hung standard delta sticky traps next to the automated traps, alternating locations each week, and she found comparable catch rates. She also double-checked the computer results with her visual inspections and found similar data.

Convinced, she expanded the use of camera traps for monitoring leafroller and codling moth over a lot more Zirkle acreage. If the company experienced oriental fruit moth pressure, she would use the traps for that pest, too, she said.

Smith also believes she gets more accurate pheromone emission and timing with camera traps, hung one per eight acres.

She has experienced some data processing limits in areas. Another challenge is the rise of sterile insect release. Currently, somebody or something has to smoosh a moth to find out if it’s irradiated or not, and the camera traps can’t do that.

However, technology will overcome those problems, she said.“It’s definitely the wave of the future.”

—by Ross Courtney

Editor’s note: Teah Smith did not collaborate with Washington State University in her 2015 test of Semios camera traps, as reported in the print version of this story in the October 2021 issue. This online version of the story has been corrected. Good Fruit Grower regrets the error.

Leave A Comment