—story by Kate Prengaman

—graphic by Jared Johnson and Kate Prengaman

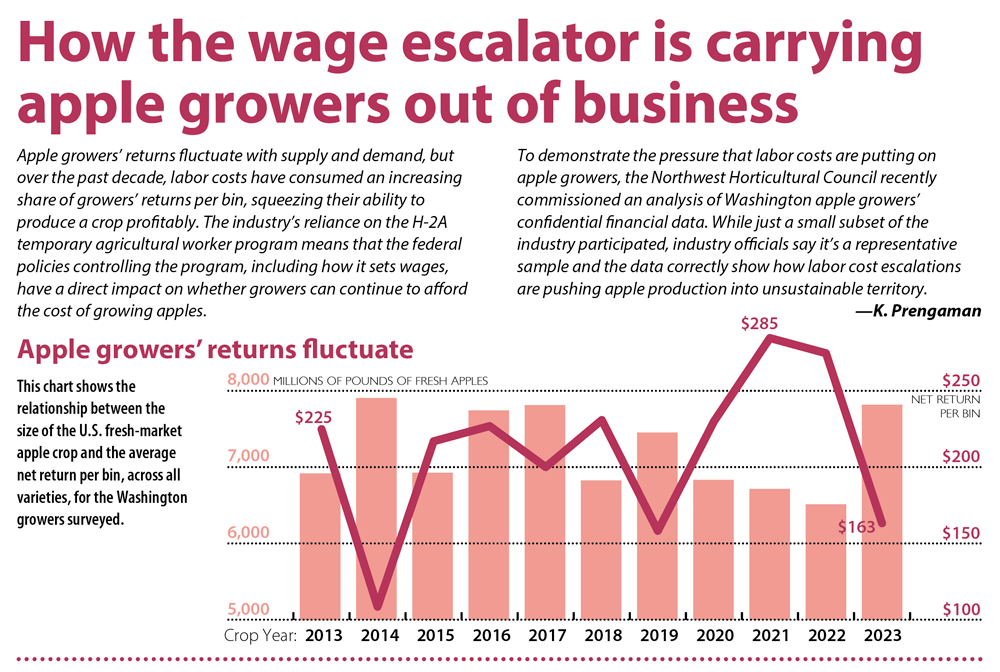

It’s been a brutal year for apple growers, who received returns below the cost of production on the bumper 2023 crop while paying record-setting labor rates to grow and harvest the 2024 crop.

The result: a cloud of uncertainty about their economic future.

“How do you survive with these labor costs?” asks Scott McDougall, president of McDougall and Sons of Wenatchee, Washington. “This industry is not sustainable unless we start getting some help on the political side with these wage increases.”

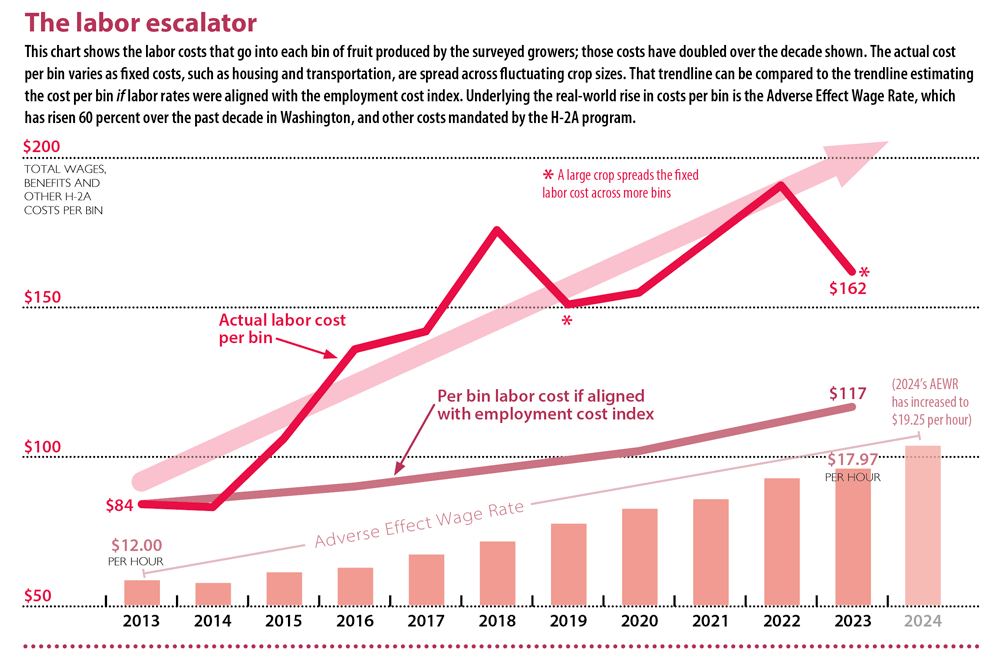

Over the past 10 years, labor costs per bin of apples have more than doubled for Washington growers using the H-2A program. That’s compared to 30 percent inflation across the U.S. economy in the same period.

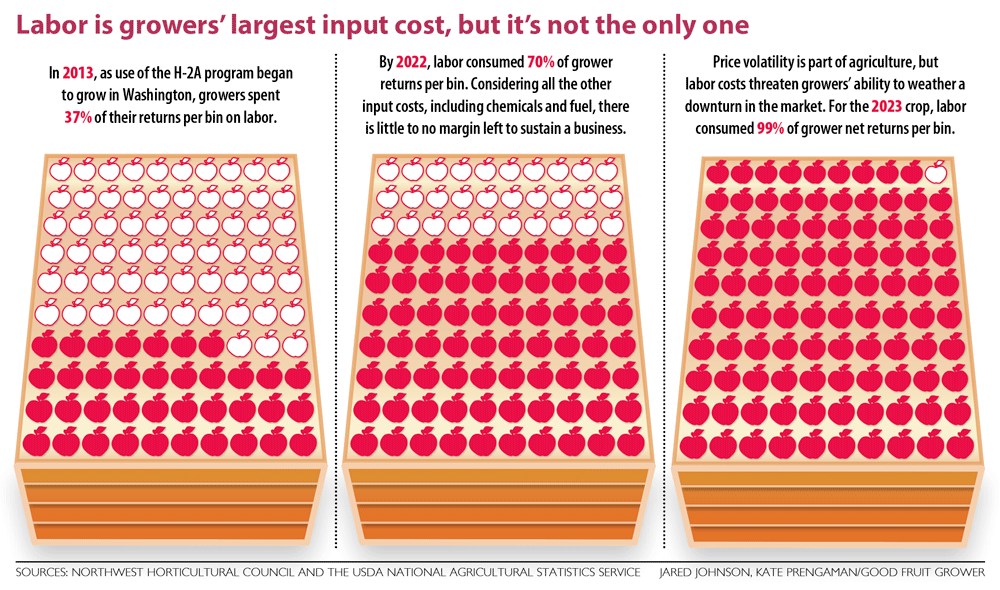

To show policymakers the squeeze that escalating labor costs put on apple growers, the Northwest Horticultural Council recently commissioned an analysis of growers’ actual financial data over the past decade, looking at the labor costs that go into every bin of fruit and the returns growers received per bin. In 2023, labor costs swallowed 99 percent of the surveyed growers’ returns per bin, leaving nothing to spare for other inputs, such as chemicals and fuel.

Click here for a printable PDF of this graphic

“It’s scary. The 2023 crop is a stark reality check” of how unchecked labor cost increases are putting growers out of business, said Mark Powers, president of the NHC, which advocates for Pacific Northwest tree fruit growers on federal policy issues.

Even if apple prices recover, the problem remains.

“Mother Nature provides different crops in different years, but if you look at the (wage and labor) trend lines, they are unsustainable,” Powers said.

NHC spent $100,000 on the analysis, which was conducted with care for the confidentiality of the sensitive business data involved by accounting firm Moss Adams. NHC declined to share the number of participating growers, but surveyed farms had a net return to the orchard of $100 million in 2022, which is about 5 percent of the state’s $2.07 billion apple crop.

Those farms opened their books so the accounting firm could calculate “an aggregated and anonymized industry representative” net return per bin after packing charges, Powers said. The data is averaged across all apple varieties for crop years 2013 to 2023, along with the wages and benefits paid per bin and the associated H-2A costs, such as housing and transportation, also averaged per bin.

The labor cost to grow a bin of Washington apples rose from $84 in 2013 to a high of $191 per bin in 2022, when a short crop meant the fixed labor costs were spread across less fruit. That’s a 127 percent increase. For the larger 2023 crop, labor costs were $162 per bin (up 95 percent from the comparably large crop of 2014), and growers received $163 per bin (down from $275 and $285, the previous two years, respectively).

The data reflect growers’ reality, according to NHC trustees who reviewed the findings. In fact, it might be an optimistic view, considering that survey respondents represent larger farms with economies of scale, said Miles Kohl, CEO of Allan Bros. in Naches, Washington.

The result is a first-of-its-kind approach to quantifying “the reality of what our growers are going through,” said Kate Tynan, NHC senior vice president. “The data allows us to show, in black and white, how dire of a situation we are in and how growers can’t wait any longer for policymakers to address this issue.”

NHC didn’t invest in this analysis to tell growers what they already know, but rather to provide “a tool to communicate the scale of the challenge,” said Sean Gilbert, president of Gilbert Orchards in Yakima, Washington, and the current chair of NHC’s board. “The industry’s reliance on the H-2A program means our cost of labor is directly tied to public policy. Anything in the public policy realm needs to be clearly communicated in understandable soundbites or graphs.”

Rather than preaching to the choir, the analysis arms the choir with facts, said Brad Newman, president of Cowiche Growers and an NHC board member. Labor costs, driven by the H-2A program and Washington’s overtime rules, have pushed growers to the brink.

“Inevitably there are difficult market periods, and we’re in one now, but it’s remarkably exacerbated by the labor rates,” he said. Overtime rules have pushed up labor costs at the cooperative’s packing house, too. “Which is passed on to the grower in packing charges, and they are paying significantly more to farm and harvest, and they don’t have anyone to pass that on to.”

In 2024, the AEWR was set at $19.75 in California; $19.25 in Oregon and Washington; $18.50 in Michigan; $17.80 in New York; and $17.20 in Pennsylvania. Meanwhile, of those apple-growing states, only Michigan and Pennsylvania continue to exempt farm work from overtime pay.

The AEWR increases also drive up the wages that smaller growers, who hire locally, must pay to compete for workers, Newman said.

As the name implies, the Adverse Effect Wage Rate was created to meet a statutory obligation to ensure the H-2A program did not adversely affect wages of local workers. Functionally, it’s become a floor, as H-2A employers are required to offer the same wages and benefits to any domestic applicants, and that in turn pushes non-H-2A employers to offer even higher wages to keep their workers, Tynan said.

Therein lies the problem: The average from that competitive wage dynamic the previous year becomes the base wage, or floor, for the next season, as determined through the wage surveys that are used to set the AEWR and Washington’s prevailing wage. Moreover, the industry’s piece-rate pay practices compound the problem of setting a base wage on the previous year’s average.

“It’s an unsustainable cycle where government-imposed wages are artificially driving up labor costs for the entire industry,” Tynan said.

It’s something she, and many others, have been trying to draw lawmakers’ attention to for years.

Tynan said the new data — showing, rather than telling — has already drawn policymakers’ attention to the urgency of the problem. NHC works with other ag labor groups to advocate for both a short-term pause in AEWR increases and long-term solutions in the form of both legislation and administrative action.

The goal is “reasonable AEWR reform,” Gilbert said.

“It’s not going away, but I do think the policy could be crafted to be fair to workers and sustainable for farmers,” he said. “Otherwise, orchards will come out, and that means less jobs for people — and under the current system, I don’t see it going any other way.” •

Leave A Comment