When Sierra Gold Nurseries delivers a batch of new trees, the company wants to know for sure the variety and rootstock match the label. So does every nursery.

Recent investments in DNA screening technology and updates to the University of California’s genetic verification procedures make it easier for nurseries such as Sierra Gold to make that promise.

“It’s the only way we can operate,” said Reid Robinson, chief operating officer at Sierra Gold. “Mix-ups are terrible for our customers, and they’re terrible for us.”

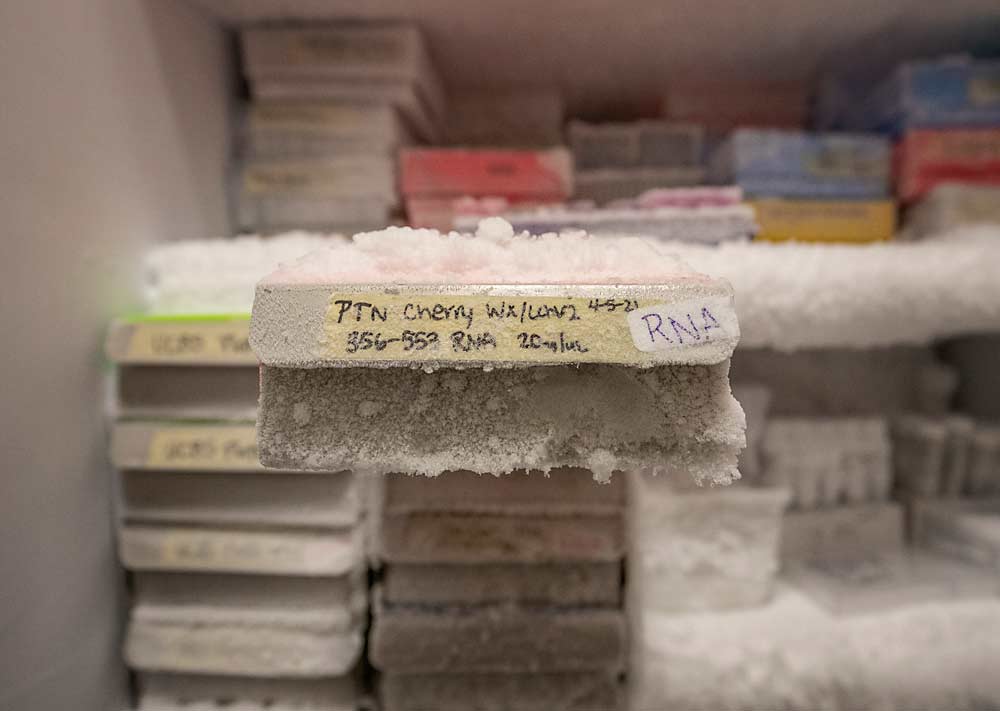

Like many nurseries, Sierra Gold of Yuba City, California, started using polymerase chain reaction, or PCR, genetic screening machines to verify plants received from breeders and to double-check the record keeping in their own tissue culture lab and budwood orchards.

The company purchased its conventional PCR machine, which deploys gel electrophoresis, in 2017 after it received from a trusted laboratory a noncommercial cherry selection mislabeled as Chelan, and unknowingly sold it. In 2020, the company purchased a real-time PCR machine. Once only the domain of well-heeled research labs, the real-time technology runs 96 tests more accurately in the same amount of time that the previous version ran 16.

“You get a lot more data, and you get a lot more reliable data,” said Micah Stevens, research laboratory manager at Sierra Gold.

Meanwhile, the system outside the nursery walls has shifted.

This year, Foundation Plant Services at the University of California, Davis began requiring customers, such as breeders, nurseries, other universities and, sometimes, growers, who bring material to the laboratory to also submit a sample of previously verified tissue — a “voucher” — for DNA comparisons, said Maher Al Rwahnih, director of the foundation. The technicians will then propagate the plant, grow it and compare it to the voucher. If it matches, they will continue to grow the trees for at least two years, for virus testing, and then they will screen the DNA again.

Previously, the foundation only tested at the end of the process, sometimes after the customers they work with had already made provisional releases.

In 2019, the foundation caught a mistake, through back-end DNA sampling, revealing that some Gisela 5 cherry rootstocks were really Gisela 6, a less dwarfing option, after the material had been provisionally released back to the customer. By then, it had reached commercial plantings. Had the foundation been using the new protocol, the mistake would have been detected sooner, Al Rwahnih said.

Mistakes such as that are uncommon, Al Rwahnih said, but they can happen.

The issue has become more urgent with the rollout of new varieties and an increase in demand for testing apples, pears and stone fruit.

“We need to all work together to avoid mistakes,” Al Rwahnih said.

Customers come to the foundation mostly for virus testing, but they get true-to-type verification as part of the package. Both are part of its mandate under the California Department of Agriculture’s deciduous fruit and nut tree registration and certification program. The laboratory charges $355 per sample for the service for fruit trees and grapevines.

That’s different than the Clean Plant Center Northwest, located at Washington State University’s facilities in Prosser, which only has a mandate to screen for disease. In fact, the Prosser lab’s contract with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Clean Plant Network expressly forbids the other testing: “The Network recognizes the importance of maintaining and verifying clonal plant identity, including trueness to type; however, DNA fingerprinting and trueness to type work may not be supported through this funding.”

In the past, the Prosser center has received state funds to genotype grapevines and used California’s FPS to fulfill that role, said Scott Harper, center director. The lab has also helped companies who request genotype services to find a private lab.

The FPS changes and private nurseries’ technology investments are “extremely necessary” in the modern tree fruit industry, said Gennaro Fazio, U.S. Department of Agriculture rootstock breeder at the Plant Genetic Resources Unit laboratory in Geneva, New York. In fact, his lab tests all material it sends out, usually tissue culture, against a historical database and asks the receiving business or agency to test it once it arrives and after they propagate it.

Even his unit has made the rare mistake. Four or five years ago, the New York laboratory tried to ship a Geneva 210 rootstock that was really something else. But Al Rwahnih tested it on the front end — though that wasn’t his requirement at the time — and caught the mistake before it was propagated for virus testing.

“The system worked,” Fazio said. “I have to give them credit, lots of credit.”

Back in Central California, Robinson and Sierra Gold are fans of Al Rwahnih’s new procedure, and not just because it covers their reputation, Robinson said. The trust-but-verify mentality is now rippling through the entire industry, adopted alike by FPS, nurseries and breeders trying to launch new varieties.

“(True-to-type) is kind of everybody’s responsibility,” he said.

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment