Dowen Jocson is an expert in psylla love songs.

The Washington State University doctoral candidate has recorded the mating calls of pear psylla. She calls them courtship duets, knows the difference between the male and female versions and uses them as her phone’s ringtones.

But Jocson and her colleagues aren’t setting up a dating app for insects. Quite the opposite. They plan to use the rhythmic signals to develop a mating disruption tool as an integrated pest management strategy, much the way pheromones frustrate the coupling attempts of codling moths in apple orchards.

Jocson’s research is funded by the Fresh and Processed Pear Committee at roughly $156,000. The project is entering its third and final year. David Crowder and Betsy Beers, WSU entomologists, and David Horton, a U.S. Department of Agriculture entomologist, serve as her advisers. The team also picked up $21,000 from the USDA Agricultural Research Service Innovation Fund to purchase broadcasting equipment for 2020, Horton said.

Pear psylla, an invasive insect from Europe, feed on the phloem of pear trees and create sticky honeydew that in turn causes fruit damage. Large populations can prevent growth, cause defoliation and fruit drop, and reduce fruit set the following year.

Like many pests, psylla are gradually building resistance to common insecticides. Growers support a variety of research projects looking for alternative controls, including reflective mulch, washing away honeydew and parasitic wasps.

There is precedent for the vibration disruption concept, both with tree and vineyard pests. Though nothing has been released commercially, researchers in the United States, Italy and Germany have published about their efforts on interruptive auditory signals for citrus psylla, treehoppers, multiple species of leafhoppers and even a closely related pear psylla in Europe.

“It’s extraordinarily encouraging,” Horton said of the leafhopper results.

Biotremology and Marco Polo

The field is called biotremology, the study of vibrations on animal behavior. Some of the world’s invertebrates indeed hear sound through the air, but psylla and others feel vibrations through a substrate, usually plant tissue. Spiders and scorpions are the same way.

Jocson earned her master’s degree from St. Louis University, focusing on how temperatures affect the vibrational communication of treehoppers. Turns out, insects raise their pitch in warmer weather.

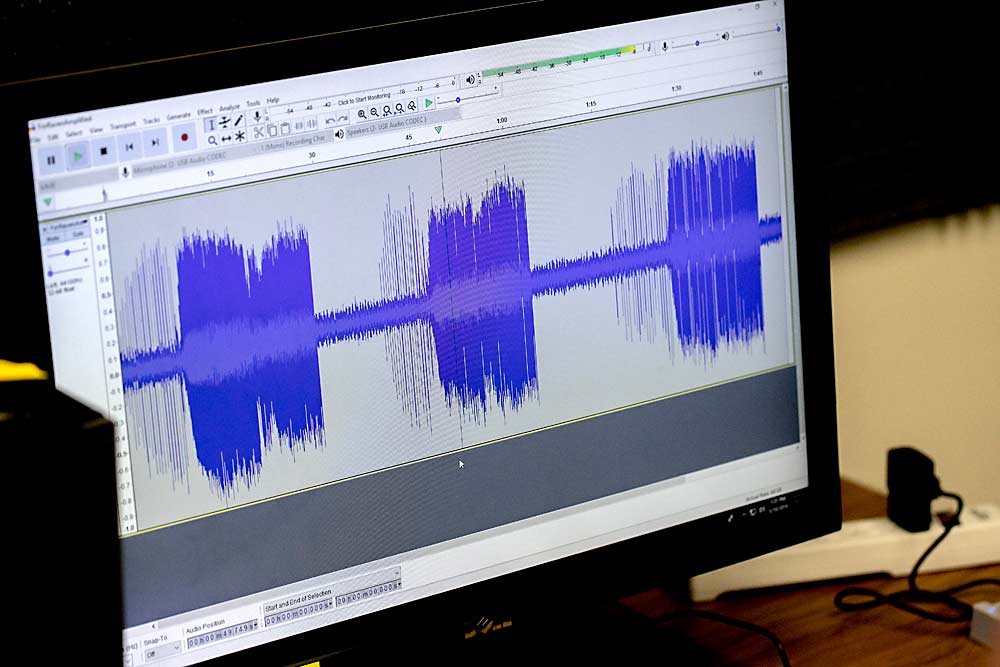

In 2018, she started at WSU, where she has been painstakingly recording vibrations of male and female psylla on potted plants hooked to sensors inside a windowless, makeshift studio.

Jocson likened the communication to a game of Marco Polo. Males make the first move, broadcasting a series of short chirps followed by a humming pattern they create by stridulating their wing muscles to create tremors that carry through the plant. A nearby female may or may not respond, depending on how she feels about the pickup line. They repeat this “duet” until they find each other, mate and reproduce. Psylla also use some pheromone signaling, but these vibrations appear to be the key to reproduction.

In theory, broadcasting artificial signals throughout the orchard should overwhelm and confuse the genders, prevent them from finding each other and, therefore, decrease their mating rates.

Getting out of the lab

The rub is moving from the laboratory to the field.

A team of researchers at the federal Julius Kühn Institute in Dossenheim, Germany, published results about their recordings of a closely related species of pear psylla, the Cacopsylla pyri. The species of concern in the Pacific Northwest is Cacopsylla pyricola.

They plan to continue recordings and lab trials in 2020 and start field trials along trellis wires next year in an institute research orchard, said Astrid Eben, the principal investigator. The recordings and trials will take time, maybe years, before they can reach commercial tests, she said, but they will get there.

“Nevertheless, I am sure that this fascinating technology will soon be one possibility of pest control,” she said in an email to Good Fruit Grower.

Meanwhile, in Gainesville, Florida, USDA entomologist Richard Mankin has been recording mating vibrations for 10 years for the Asian citrus psylla, which vectors the bacteria that causes citrus greening. His team explores a mixture of mating disruption and using the signals for traps. They even discovered how to combine traps with green lights to boost their catch rates.

“Unfortunately, we’ve just never been able to move it out of the lab,” Mankin said.

Equipment to broadcast the signals to a large grove is expensive, he said. Citrus farmers don’t use trellises, though he plans this spring to run wire through some test orchards, to carry the vibrations.

Scientists in Italy working with vineyard pests have come the closest to commercialization. From 2017–2019, after more than 10 years of lab research, a team of scientists at the Fondazione Edmund Mach Research and Innovation Centre in Northern Italy broadcast vibrational mating calls of male and female leafhoppers along trellis wires in a commercial vineyard. It worked, said Rachele Nieri, part of the Italian team. Populations decreased in Cabernet Blanc blocks by 50 percent in 2018 and 2019, compared to the control.

In 2018, Nieri joined Oregon State University in Corvallis as a postdoctorate researcher in Nik Wiman’s pest lab and began doing similar work on treehoppers that vector the grapevine red blotch virus. Rather than mating disruption, Nieri and her colleagues are trying to use the signals as a trap lure for the treehoppers. They just launched a similar study with the goal of improving a trap for the brown marmorated stink bug, developed at the same Italian institute.

The mating disruption approach works better with insects that tend to stay on one plant, such as psylla, while trapping works better with pests that frequently fly from place to place, Nieri said.

In spite of the commercial hurdles, she believes in the technology’s potential because most insects in the world use vibrations to communicate, and mating calls are species-specific.

Back at WSU

Jocson also believes the idea will work, but as a researcher, she tries not to think about the commercial hurdles. Yet.

“I’m trying to take it step by step, because if I think about the orchard aspect of it, I will be immobilized,” she said.

This year, she will continue to record more signals and start cage trials with populations of both males and females. Some will be treated with the recorded male and female signals; others will not. After letting the psylla mingle for a while in the two environments, she will measure reproductive rates by counting nymphs and catching females to dissect them and count spermatophores, which will tell researchers how many times the female psylla has mated.

Jocson also experiments with different broadcast methods. Not all pear orchards have trellises. Perhaps a mini-shaker, used in earthquake preparation, could be placed on the trunk of each tree, or a loudspeaker could vibrate the air enough to shake the tree branches. She also plans to test the use of a female call for a trap.

Beers, one of Jocson’s WSU advisers, sees the potential as well. After all, who would have thought pheromones would work on codling moth 30 years ago?

“It was a far-fetched dream, it was pie in the sky,” Beers said. “So, my feeling is: Who knows where the next pie is?”

—by Ross Courtney

Related:

—Sugar substitute keeps pounds and pests at bay

—Reflective mulch proves repellent

—Sustainable and less sticky solutions for pear psylla

This is great research. There is too perfect a pun here comparing the McCartney classic to this: Psylla Love Songs? It’s even by Wings!

Oh yes, this story begs for puns and I wish I would have thought of this one myself. Good catch, Chris. To enlighten those unfamiliar, Chris refers to the 1976 “Silly Love Songs” by the band Wings, when it was fronted by the legendary Paul McCartney post-Beatles. I’ll share it here: https://youtu.be/ap87QgZKTNw