—by Ross Courtney

Alcohol consumption is dropping, but certain Washington wine varieties show growth. While the state’s large companies have cut volume, some smaller wineries are thriving with direct-to-consumer sales. Bulk wine inventories remain much too high, but some price points look encouraging.

Washington wine leaders painted a nuanced picture of an unpleasant reality with pockets of optimism during the annual State of the Industry panel at WineVit, the annual meeting of the Washington Winegrowers Association, in February in Kennewick.

“We’re going to come out of this a smaller and healthier industry,” said Erik McLaughlin, CEO of Metis, a Walla Walla wine industry advisory firm.

The five speakers didn’t try to sugarcoat anything as they discussed an industry still reeling from multiple years of acreage and volume cuts by its largest producer, Ste. Michelle Wine Estates. But they encouraged the audience to confront challenges without wallowing.

“Being kicked in the stomach over a tough market isn’t a strategy,” said Adam Schulz, owner of Incredible Bulk Wine Co.

Prioritization may be in order, said McLaughlin, who helps arrange winery and vineyard purchases. He encouraged businesses to take care of themselves before trying to bolster the whole state.

“You can’t help your neighbor until you secure your own oxygen mask first,” he said.

The 30-year tide of overall growth in wine consumption has receded and won’t return, he said. Competing for market share is the only option. If enough businesses do that, the state will start to capture share from other regions.

McLaughlin shared a chart of financial benchmarks to help wineries with such introspection. He usually hesitates to give such advice — because businesses differ, and the benchmarks assume Generally Accepted Accounting Principles, something not every small winery uses.

“This is information that I am often asked for and reticent to give, because the answer for ‘What does a healthy winery business look like?’ is complex,” he said.

For example, in his opinion, an “OK” gross margin for wineries with a blended wholesale and direct-to-consumer business model is about 50 percent, while healthy wineries should have no more than 18 months of bottled inventory on hand.

Sizing down

The state’s industry is “correcting” in size, said Kristina Kelley, executive director of the Washington State Wine Commission.

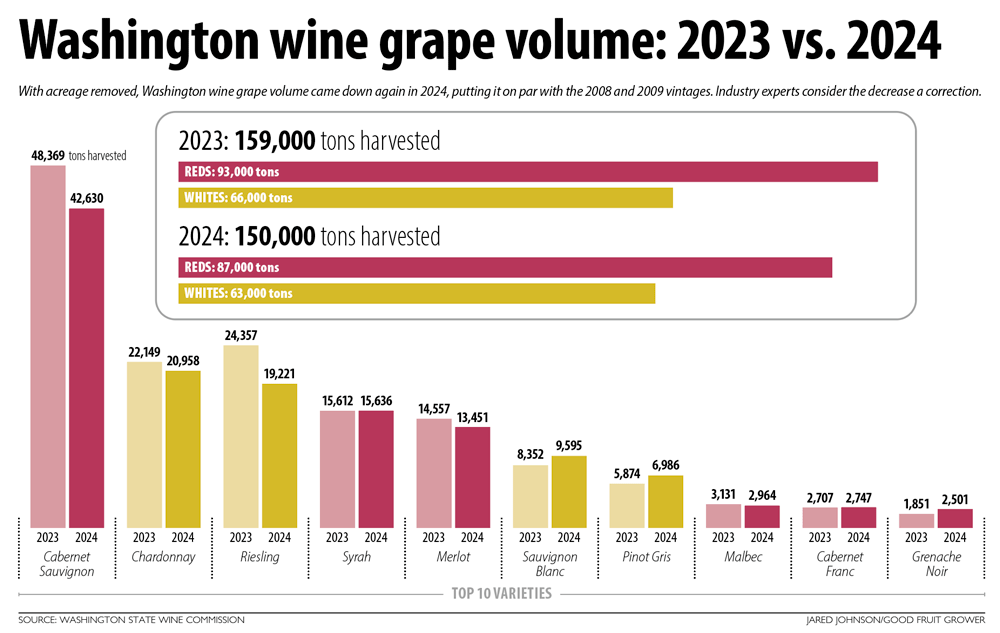

The state crushed 150,000 tons of wine grapes in 2024, down from 159,000 the previous year, according to preliminary annual data. That resembles the levels of 2008 and 2009.

Total shipments of Washington wine declined 6 percent through October, smaller than the double-digit drops of the previous two years. The state now has about 50,000 acres of wine grapes, down from about 60,000 a year ago.

Washington is not alone, Kelley said. California also had its lowest harvest volume in 20 years, down 23 percent from 2023, with 2.8 million tons in 2024. France’s wine grape acreage has contracted, too, and U.S. consumption of wine, beer and spirits has dropped since a peak in 2020.

“It’s important to know it’s not just wine, it’s not just Washington, it’s not just United States,” Kelley said.

To thrive in the smaller world, industry experts stressed quality over quantity. Many of the speakers touted the $15–$25 price point as ripe for opportunity. Wholesale shipment data from SipSource showed Washington wines in this category grew by 17 percent from October 2023 through September 2024.

“That’s where we might want to spend some time,” Kelley said, though she expected those figures to soften after adding data from October through December.

That price range makes up about 15 percent of the Washington market, while wines below that represent more than 80 percent.

Ryan Hill, director of education and promotion for Evergreen Family Wines, suggested aiming for that price point but also raising prices overall, both on existing brands and new ones.

“Where these wines are priced at right now, we are leaving so much money on the table,” said Hill, who considers himself a promoter for the whole state.

Evergreen recently purchased some Milbrandt and Ryan Patrick brands and raised prices on them, Hill said. It might cause some temporary discomfort but will pay off in five years or so.

McLaughlin of Metis urged wineries to shoot for $20 to $35 per bottle.

In a follow-up interview with Good Fruit Grower, McLaughlin agreed that Washington wines have been underpriced, but he does not believe shoppers will tolerate boosting prices on existing bottles now.

“Ultimately, I think very few individual brands have the pricing power to increase price in this market,” McLaughlin said.

Price hikes or not, Schulz urged the crowd to start bringing new ideas to the table.

He told an encouraging story of Gratsi, a company that sells zero-sugar, boxed Washington wine at twice the normal prices by marketing based on quality-of-life and sustainability messages. The company grew from 2,000 to 350,000 cases in three years.

Schulz consulted for Gratsi, founded by an Alabama man. Washington wineries Tagaris and Four Feathers have both made wine for the new brand.

Other creative efforts include distilling excess wine into brandy or vinegar, Schulz said.

“We need to think about it much differently than we do,” he said. •

Leave A Comment