Editor’s note: After the April 1, 2022, issue was printed, we were deeply saddened to learn of Pennsylvania fruit grower Bruce Hollabaugh’s unexpected death on March 13. Hollabaugh and his family farm, Hollabaugh Bros., is featured here in our coverage of the International Fruit Tree Association’s annual conference and tour of Pennsylvania fruit farms in February. For a reflection on his contributions to the industry, see: “Remembering Bruce Hollabaugh: 1980–2022.”

Pennsylvania’s tree fruit industry is centered in its south-central region, much of it in Adams County, where orchards sprawl across the hills that circle the town and historic battlefield of Gettysburg.

Like much of the U.S. apple industry, those orchards have modernized over the years, and they now feature tighter spacings, smaller trees and a broader varietal mix than they did a few decades ago. Growers have also shifted their focus from processing to fresh sales.

Despite that shift, Pennsylvania’s apple output remains steady. The state routinely yields 10 to 11 million 42-pound bushels of apples per year on about 22,000 acres, making it the fourth largest apple-producing state after Washington, New York and Michigan.

Members of the International Fruit Tree Association witnessed the modernization of Adams County orchards firsthand in February, during IFTA’s 65th annual conference and bus tour.

One of the tour guides was Rob Crassweller, a longtime Penn State University professor and extension specialist. Crassweller, who retired after the conference ended, used his career to frame the orchard evolution. When he joined Penn State in 1984, most of the state’s apple crop was processed. Trees were “big, tall and scraggly,” he said, and growers considered about 600 trees per acre to be high density. The state’s main variety was York Imperial, an oddly shaped apple grown for its abundance of flesh, he said.

By the time Crassweller retired in February, fresh apple sales had overtaken processing, with much of the change driven by retail stores and farm markets in populous Eastern Pennsylvania. In Adams County, most growers send their apples to Rice Fruit Co. for fresh packing, but many are still sold to Knouse Foods, the region’s lone remaining processor, he said.

Penn State

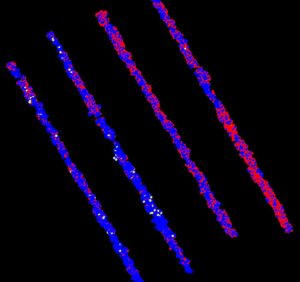

IFTA’s Adams County tour included a stop at Penn State’s Fruit Research and Extension Center, which has served the region’s fruit growers for more than a century. The group visited the recently built ag engineering building, home of professor Long He’s Agricultural Robotics and Sensing Lab. He and his team of graduate students demonstrated some of the projects they’re working on, including a robotic green-fruit thinning system, precision blossom thinning/pollination machine, sensor-based irrigation system, airblast sprayer with lidar sensor for measuring canopy density (see “Lidar technology aims for accurate sprays”), and drones that use sensors to detect fire blight and frost (see “Frost defense by air and ground”).

Hiring He in 2018 reflected Penn State’s renewed emphasis on precision agriculture and robotics for specialty crop production. Much of the funding for the lab’s work comes from the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the State Horticultural Association of Pennsylvania, He said.

IFTA also visited a peach block at the research center, where pomology professor Jim Schupp discussed his NC-140 rootstock trials. Schupp said peach growers are finally on the cusp of having size-controlling rootstocks, much as apple growers were a few decades ago.

“Size-controlling rootstocks for peaches has been a long-term goal of pomologists ever since I can remember,” he said.

Schupp’s peach block included trees on MP-29, Rootpac and the Controller series of rootstocks, ranging in size from about one-third to about three-quarters the size of a standard peach tree. They’ve all shown potential for high-density peach plantings, but tighter spacings have thrown up a few “caution flags,” he said.

Fully dwarfing trees on size-controlling rootstocks will probably need some sort of tree support, which peach growers aren’t used to. And high-density peaches can’t be planted as closely as apples. Any tighter than 4 by 12 feet or so and the fruit ends up too small, even with robust fertilization and trickle irrigation, Schupp said. (Watch for more coverage of high-density peach research in our July issue.)

Commercial stops

IFTA also visited a couple of multigenerational family farms.

Hollabaugh Bros., a diversified fruit and vegetable farm and retail market, has been managed by the Hollabaugh family since 1955. Retail manager Ellie Hollabaugh Vranich said the family built its current farm market building in 2012, after a lot of planning. The new facility helped them branch into baking, prepared and gourmet foods; host tours, festivals and other events; conduct cooking classes and workshops; sell gift baskets and run a CSA (community-supported agriculture) program — anything they could think of that might attract customers, she said.

Wayne Hollabaugh, assistant wholesale manager, said they grow nearly 50 varieties of apples. A small percentage is sold through the on-farm market, with some sent to Knouse Foods for processing and to Rice Fruit for fresh pack, but most apples move through the Hollabaughs’ wholesale building, where they’re destined for sale up and down the East Coast.

Out in the orchards, production manager Bruce Hollabaugh discussed the family’s pear, peach and apple plantings. Pears, including Asian pears, have never made up a major portion of the family’s tree fruit acreage but are an important component of their marketing strategy. The two biggest limitations are fire blight and pear psylla. Dwarfing rootstocks help control vigor, and some are more resistant to fire blight, but pear psylla remains a major challenge.

“We’re known for growing pears,” Hollabaugh said. “We try to be known for good-quality, good-tasting pears. Some of the newer varieties have helped with that.”

At Mt. Ridge Farms, vice president and fifth-generation grower Blake Slaybaugh discussed pruning in a 34-acre Premier Honeycrisp block. They grow about 90 acres of Premier Honeycrisp overall, so they’re very busy with harvest in early August. The block was planted a few years ago at a 12- by 3-foot spacing on multiple roots, including Nic.29 and Geneva 11. It’s had some problems with fire blight. As far as crop load management, their goal is to have about 80 apples per tree, he said.

David Slaybaugh, company president and Blake’s father, showed off Mt. Ridge’s equipment shop and repair facility. With its three bays and endless shelves of tools and spare parts, the building is a gearhead farmer’s dream. When the Slaybaughs built it in 2004, they wanted something larger than the previous facility, with an office and bathroom attached. They needed a 16-foot ceiling and 14-foot bay doors, so they could fit any piece of farm equipment that needed fixing, whether it be a tractor, truck, forklift, hedger, leaf blower, mobile platform or something else. They even keep the floors warm with radiant heat, to make winter repair work more comfortable, David said. (The Slaybaughs are widely recognized as progressive when it comes to mechanization in the region; our May 1 issue will feature a look at how they are using tools to reduce labor inputs.)

No tour of Adams County tree fruit would be complete without visiting Rice Fruit Co., a packer, shipper and marketer of fresh apples that serves about 40 farm families throughout the region. Founded in 1913, Rice Fruit is now managed by the fourth generation of the Rice family.

Ben Rice, current president, summarized some of the company’s cutting-edge technologies and capabilities for the IFTA audience. He said the packing lines are still the “heart of what we do.” There’s the so-called Gray Line, a four-lane Compac machine that can pack about 600 bushels an hour, and the Blue Line, another Compac line that can pack about 1,000 bushels an hour. Both lines include internal quality sorting, an important and growing part of the company’s business strategy.

Rice also mentioned the company’s robotic palletizers, added in 2019. Each of the three machines can palletize up to four unique products at a time, which has greatly sped up their packing process, he said.

Grower services manager Lee Showalter said Rice Fruit tests crop size and quality thoroughly throughout the season, starting with preharvest surveys to gauge the coming crop size and continuing with preharvest and postharvest testing for Brix, starch and freshness. Every bin is tagged by grower, farm, block and variety. They perform a similar round of testing after the fruit comes out of storage, he said.

—by Matt Milkovich

Leave A Comment