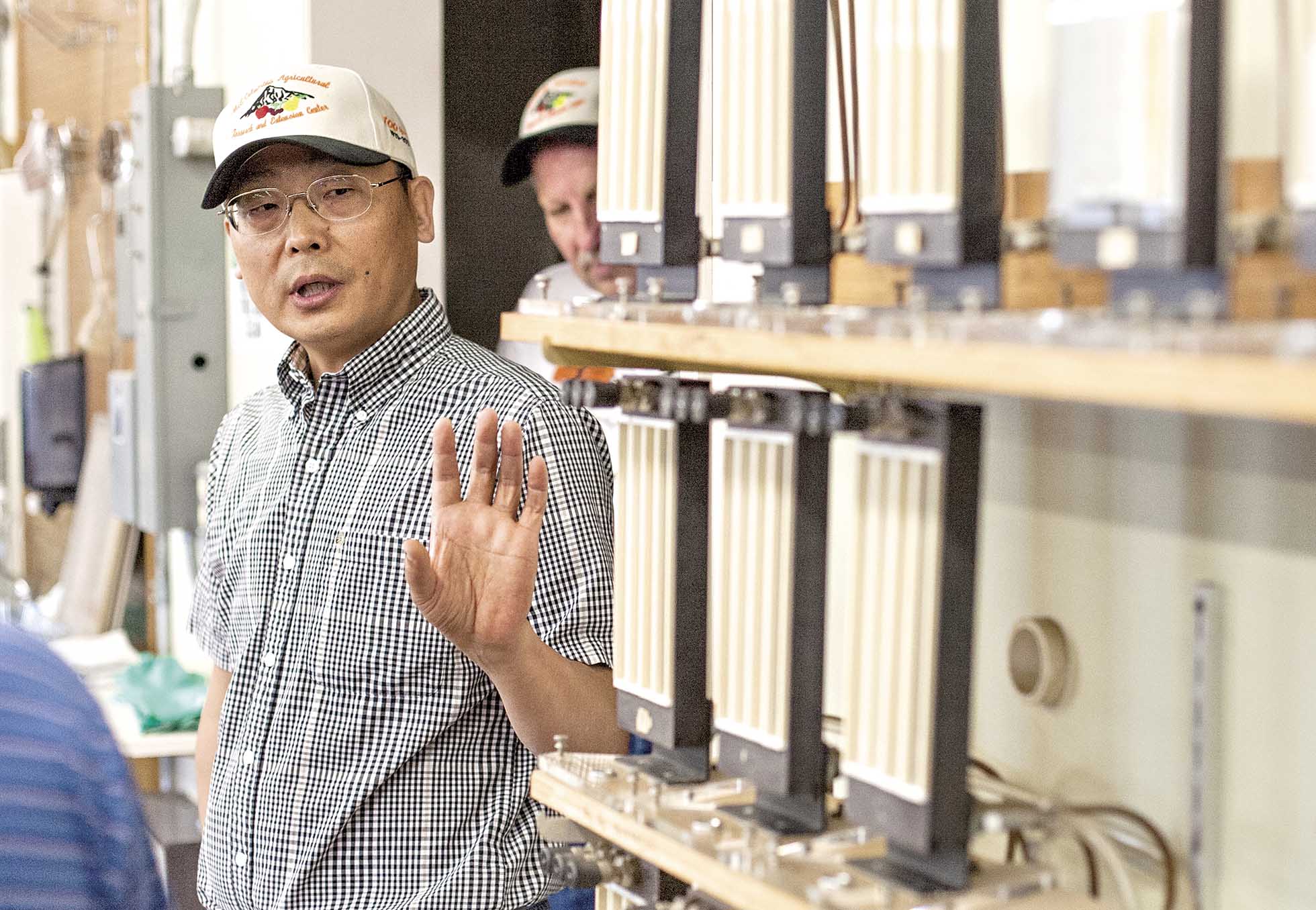

The late Oregon State University researcher Yan Wang talks about postharvest lab instrumentation for measuring levels of oxygen, nitrogen and carbon dioxide within several storage chambers at the university’s Mid-Columbia Research and Extension Center laboratory in Hood River, Oregon, in 2013. Wang died last spring. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

Storing d’Anjou pears presents packers with a Catch-22: use 1-MCP to prevent superficial scald and extend the storage season and risk the fruit losing its ability to ripen; skip it and the window for quality fruit shrinks.

“With Anjous, we have this seemingly intractable problem with superficial scald,” said Steve Castagnoli, director of the Oregon State University Mid-Columbia Agriculture Research and Extension Center, where pear postharvest science is a program priority.

Recent research shows that 1-MCP (1-methylcyclopropene) boosts the benefits of the standard scald-prevention practice, the antioxidant ethoxyquin, and could also be used as an alternative, if there is a reliable way to ensure ripening.

Therein lies the challenge many postharvest researchers are trying to solve, Castagnoli said.

OSU postharvest scientist Yan Wang was leading an ambitious research program to find solutions to this problem, and others, when he died unexpectedly last spring.

It was a huge loss to the center and the industry, but his team, which includes postdoctoral researcher Yu Dong and Wang’s wife, Caixia Li, who works as the program’s research technician, has carried on the work and met all the 2017 objectives, Castagnoli said.

Those objectives include basic science approaches to understand the chemistry of pear ripening and scald development, as well as applied solutions such as conditioning and storage regimes and edible coatings to reduce scald and superficial damage. On the cherry front, the lab is also looking at the best methods for maintaining fruit quality during ocean shipping.

“Yan was really good at looking at a problem, developing an approach to thoroughly understanding the physiological mechanisms, and then developing practical approaches to managing or preventing the problems,” Castagnoli said. “But like a lot of issues, there’s not a quick fix. This work does take time.”

Oregon State University researcher, Yan Wang, right, talks about the Mid-Columbia Research and Extension Center laboratory on August 8, 2013, in Hood River, Oregon. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

Projects on both pears and cherries receive funding from the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission, the Columbia Gorge Fruit Growers Association, the Northwest Fresh Pear Research Committee and the Oregon Department of Agriculture.

Pears

It’s no secret in the pear industry that the silver bullet for apple storage, 1-MCP, is more complicated when it comes to conditioning pears.

The ethylene blocking compound does prevent senescence disorders such as scald and extends storage life in pears, but treated pears often fail to ripen properly after storage. For apples, staying crisp is an asset, but in pears when a buttery-juicy melting texture is desired, it’s a major liability.

To make matters worse, the problem is unpredictable. Harvest maturity, temperature during the growing season, fruit calcium content and storage temperature all appear to play a role in how the fruit responds to 1-MCP.

In 2014, Wang found that d’Anjou pears treated with 1-MCP and stored at 34 degrees for eight months maintained ripening capacity with minimal scald, while those stored at 30 degrees did not ripen.

It’s a narrow window, as storage at 36 degrees resulted in pears that lost quality and developed an unwanted mealy texture.

Oregon State University researcher, Yan Wang, left, replies to a question from OSU president Edward Ray, far right, on August 8, 2013 in Hood River, Oregon. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

“It’s simple metabolism,” explained Rob Blakey, former postharvest extension educator for Washington State University. To ripen properly after storage, the fruit needs to metabolize just enough during storage to make some new ethylene receptors to replace those blocked by the 1-MCP, Blakey said. Store too cold and the fruit metabolism is too far suppressed to do that.

For the best development of the buttery-juicy melting texture in d’Anjou pears, Wang recommended harvesting fruit at 14 to 15 pounds of firmness and utilizing controlled atmosphere long-term storage.

He also found that orchard elevation, and therefore cold conditions during the growing season, impact how much postharvest chilling is required for the fruit to trigger ripening.

Lastly, the project showed that post-storage ethylene conditioning improved ripening of 1-MCP treated pears after long-term storage.

Part of the most recent research effort also examined ripening at a chemical level to see what compounds and processes were most critical to the development of tasty pears.

“The new finding is that the water-soluble pectin had a high-positive correlation with buttery-juicy texture development. It not only occurred in Comice and d’Anjou pears, but also proved in Starkrimson, Bartlett, Red Anjou, and Bosc,” said Yu Dong in an email interview.

1-MCP treated winter pears showed lower levels of these key water-soluble pectins, the presence of which indicates that the structural pectin in the fruit’s cell walls are being broken down to soften the fruit.

“They’ve made inroads on the basic research of the ripening process and the development of commercial protocols for 1-MCP and CA and temperature regimes,” Castagnoli said. “The next step is more work to understand scald development and look for other ways of managing scald that would not affect the ripenability to make the process simpler, easier and more affordable, so that it’s more likely to be a commercially viable approach to dealing with scald.”

In addition to exploring the basic biology of scald, researchers plan to look for ways to enhance the natural antioxidants in the fruit peel to reduce susceptibility and to explore if edible coatings mixed with ascorbic acid could provide an alternative to DPA (diphenylamine) or ethoxquin as scald preventers, Dong said.

Cherries

Dong presented the latest findings on how to best protect cherry quality for ocean shipping at the Northwest Cherry Research Review in November. Building from Wang’s earlier findings that weekly preharvest calcium sprays at 0.1 percent increase fruit calcium levels and boost firmness, his lab then turned its attention to the mechanisms of flavor.

“The most interesting finding is that the acid plays an important role in flavor deterioration,” Dong said. Malic acid loss, which occurs through respiration in sweet cherries, appears to be the leading cause of bland flavor.

Knowing that, researchers are now focusing on how to maintain those acid levels, such as postharvest treatments with calcium or certain plant metabolites in the hydrocooling water, Dong said.

Next, they want to identify the key flavor compounds for each cherry cultivar and further investigate how growing conditions such as heat and humidity impact flavor deterioration, he said.

Fruit nutrient levels also seem to play a role in flavor as well as firmness. “Calcium levels in cherry fruit indeed affect the flavor deterioration,” Dong said. “But we don’t want the farmers to spray more calcium on cherry, because there (needs to be) a balance among all nutrient compositions.”

Intriguingly, the data shows some cultivars seem to maintain their flavors better than others, suggesting that Sweethearts and Skeenas may be better candidates for ocean shipping than Lapins or Bings.

“It’s better to understand what kind of cherries could maintain longer flavor life,” Dong said, so packers aren’t fighting an uphill and expensive battle to preserve quality of cherries less suited to storage. •

by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment