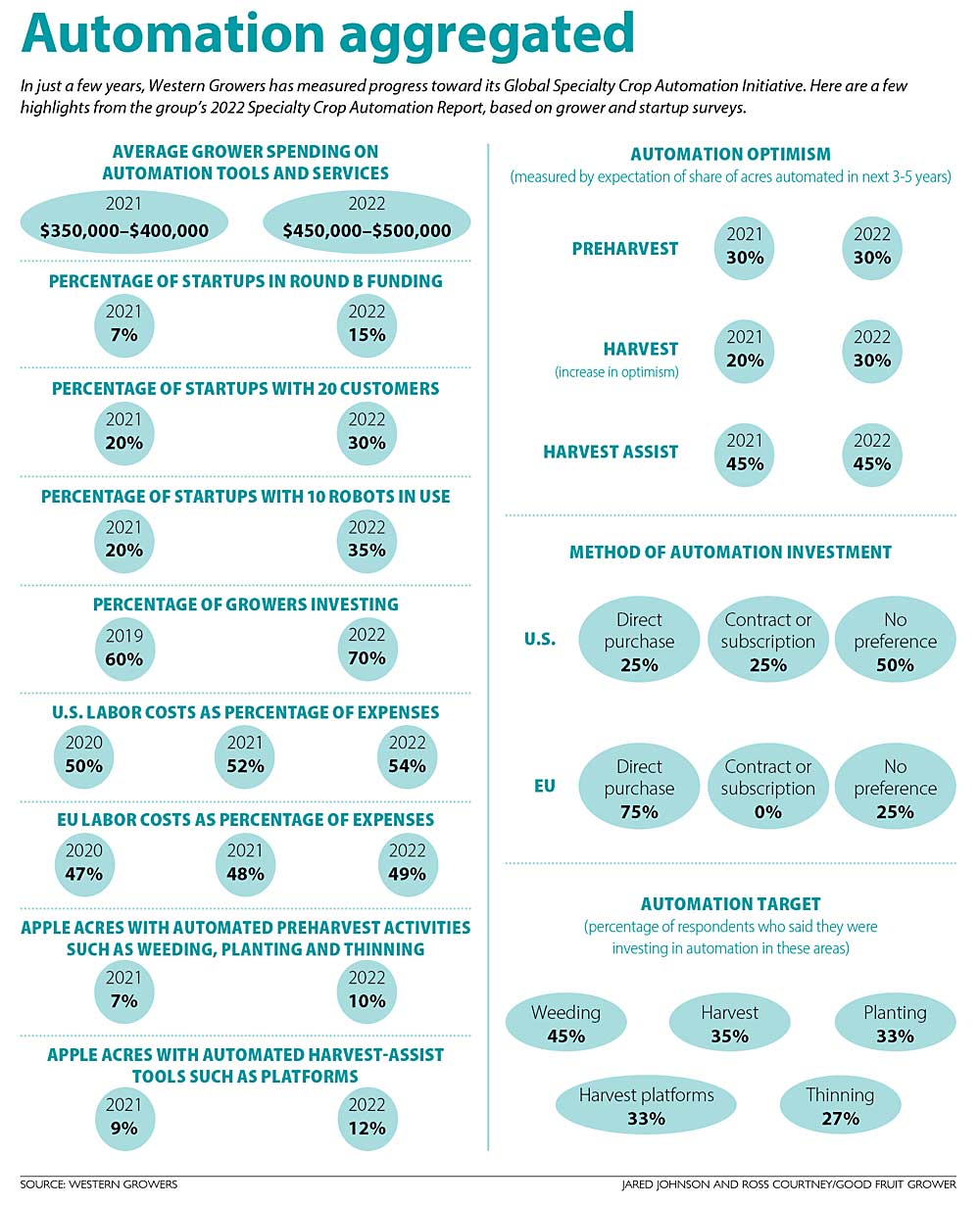

The goal of the Western Growers’ Global Specialty Crop Automation Initiative is to automate 50 percent of specialty crop tasks in 10 years.

To track progress, the group published an accounting of automation startups and the adoption of their technologies, all based on surveys of startup companies and growers in Europe and North America.

“Who is getting money? Who is getting scale?” said Walt Duflock, vice president of innovation for Western Growers, a specialty crop trade association based in California. “And who is doing it with a product that works for grower economics?”

Growers in Europe and North America spent about $500,000 on automation in 2022, up from about $400,000 the previous year, according to the 128-page document. Among the startups surveyed, 30 percent reached 20 paying customers last year, up from 20 percent the previous year.

Numbers like this matter for measuring and communicating how much the progress of technology makes up for the scarcity of labor in specialty crops, Duflock said. Eventually, he and his colleagues would like to quantify how much every dollar spent on innovation closes the labor gap.

“That would help us ask for grants,” he said.

The facts and figures help the industry talk to investors and policymakers in language they understand, said Ines Hanrahan, executive director of the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission, one of the founding collaborators in the Global Specialty Crop Automation Initiative.

Specialty crop technology financing is a tough sell, Hanrahan said. Each individual industry — apples, lettuce or tomatoes — taken by itself doesn’t offer enough scale to lure investment. Measuring them together in one report makes them more attractive.

“If we put all the specialty crops together, we can convince big companies … to start playing in this market,” Hanrahan said.

Many of the needs and tools for those individual industries overlap. For example, engineers at advanced.farm of California first invented robots to pick strawberries then pivoted their technology to work in apple orchards, where they began trials in 2022 in Washington.

“We’re in good shape because we learned so much on strawberries,” Duflock said.

Weeding tools are following the same trajectory, he said. Artificial intelligence-driven weeders using lasers, blades or sprays are learning to recognize more invasive plants in more crops every month. Three of the four major robotic weeder startups collectively raised nearly $150 million in the past 12 months, Duflock said. The fourth did not publicize its financing.

Here are a few more highlights of the automation report:

—15 percent of startups had completed Round B funding by the end of 2022. Round B is the second, usually larger tranche of investment, used to start marketing a finished product or service to customers at scale.

—35 percent of startups have at least 10 robots in their fleets, compared to 20 percent in 2021.

—Western Growers also surveyed European growers, who favor direct purchases of technology over contracted services, the opposite preference of U.S. growers.

—54 percent of European growers call labor their biggest problem; 33 percent of U.S. growers consider it the top challenge.

—As technology progresses, so do the skills required of workers. About half of growers surveyed said they have employees who spend most of their time integrating technology. “The investment is not just the robots or service, it’s the people inside the company,” Duflock said.

The report also features narratives about companies putting technology to use. For example, a California table grape producer said it had cut its costs of production by 20–30 percent through the use of Burro’s autonomous harvest-assist wagons, while a leafy green producer in the Southwest now uses two different precision weeding machines — one laser-powered, another that uses blades — depending on the crop.

—by Ross Courtney

WANT TO READ MORE?

Download the 2022 Specialty Crop Automation Report, which Western Growers released in April, at: agharvestreport.com.

Leave A Comment