The 2023 bumper apple crop spells bad news for growers’ 2024 finances: The volume is driving down prices as labor costs soar.

“This 140-million-box crop is going to be incredibly difficult to sell,” said Jeff Baldwin, sales director at Sage Fruit Co. of Yakima.

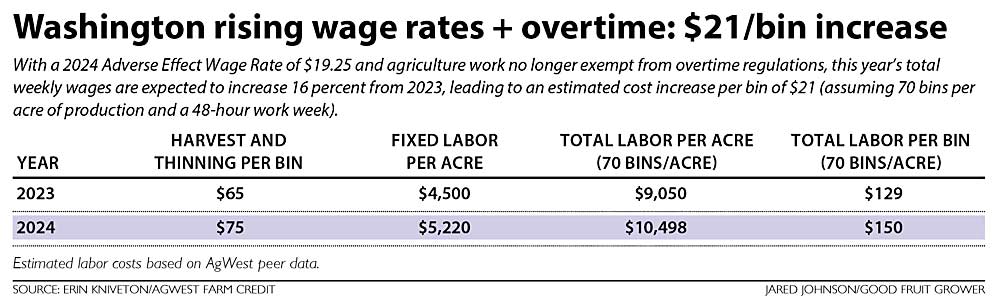

Meanwhile, growers everywhere continue to contend with rising Adverse Effect Wage Rates. In Washington, the $19.25 per hour wage, combined with overtime pay required over 40 hours, will push up labor costs 16 percent, according to Erin Kniveton, a relationship manager at AgWest Farm Credit. That translates to a $21 per bin increase in labor inputs through the season, assuming a 48-hour workweek.

Finding profitability amid such circumstances may be daunting, but it’s possible by focusing on quality and size targets and being cautious about new plantings, according to Baldwin, Kniveton and other speakers at a profitability session at the Washington State Tree Fruit Association’s annual meeting in December.

“I’d like to congratulate you all on a large and beautiful crop of high-quality apples. The problem is, it’s 140 million boxes,” said Jordan Matson of Matson Fruit, the session manager, by way of introduction. “Over the past three seasons, we’ve acclimatized our domestic and international buyers on how to market a small crop, and do it well. Now, we have to fight our way back into the shopping baskets of our consumers. And while this fight ensues, our orchards will continue to suffer at low returns.”

Set the scene

Prices fell as shippers across the U.S. worked to move 173 million bushels that sat in storage as of early December, according to the U.S. Apple Association, a crop that was up 20 percent from the five-year average. Movement remained strong, and early season exports were up compared to last season and the five-year average.

While export markets will be needed to help move the large crop, the domestic market is where the money is, Baldwin said.

To maximize crop value, the best thing growers can do is hit size targets for each variety. He shared a chart with average f.o.b.s for tray-packed boxes of Washington’s core varieties over the previous five years. Generally, prices peak around the 72-size range, and above the 80s and 88s the price is discounted. For Honeycrisp, that’s the difference between $43.66 for 72s and $36.74 for 100s.

“Growers need to understand what that sweet spot is,” he said.

The trend matters even more with a crop so large that the smallest fruit aren’t worth packing. However, 2023–24 pricing is “down across the board” from his examples, Baldwin said. One example: The December pricing for Honeycrisp was more than $10 off from the averages he shared, thanks to a record-setting Honeycrisp crop across the country.

“We had a phenomenal growing year, and you’ve grown some fantastic apples,” Baldwin said. “Packouts are up anywhere from three to six packs per bin.”

That increased packout typically translates to good news for growers’ pockets, yes, but the U.S. Honeycrisp holdings at 26.5 million bushels in December (compared to a five-year average of 17.5 million) suppressed prices into the new year.

In a follow-up call, Baldwin walked through the math. In 2022, a grower with Honeycrisp packing at 10 packs per bin with an average price of $43 would generate $430. This season, say the packs are up by three per bin but each box is selling for $30, which generates just $390. Subtract the packing charges, and that leaves growers with $250 to $275 per bin.

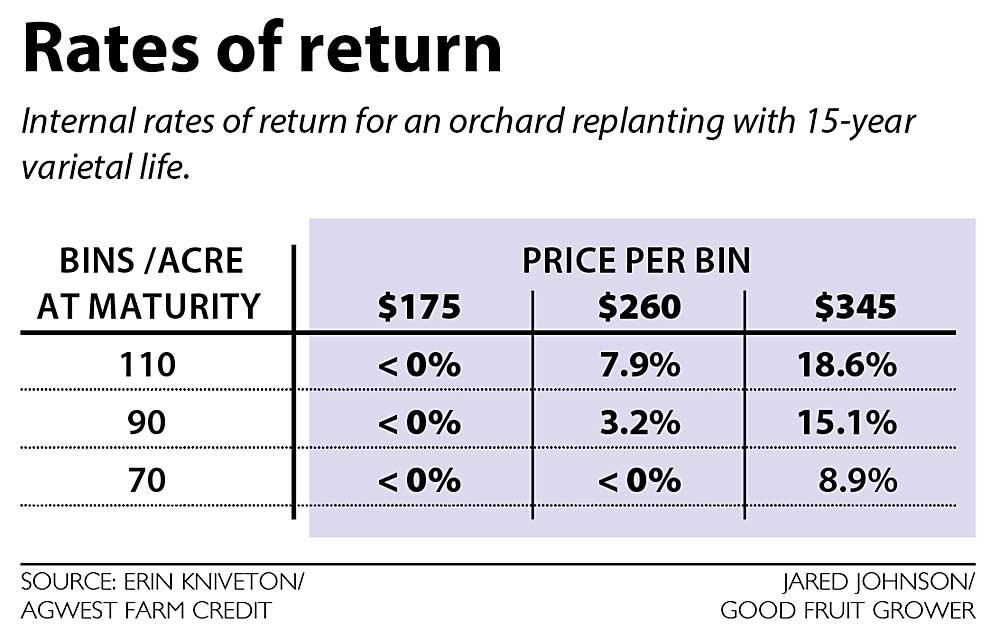

At those prices, even Honeycrisp blocks may struggle to deliver a return on investment today. Ideally, growers want rates of return over 10 percent within 15 years of planting a new block, Kniveton said. But her recent calculations show that at $260 per bin returns, even orchards producing 90 or 110 bins per acre will not hit that bar with 2024 labor costs and interest rates.

“It’s possible for high-density orchards to offer a positive return, but even at 70 bins per acre at $345 per bin, it’s risky,” she said. “In these current economics, it does not make any sense to develop orchards as a producer.”

Due to the economic challenges, she recommended growers hold onto their cash — to the tune of one-third their annual operating costs.

“What we are seeing is that producers with more working capital have more staying power,” and the ability to weather the downturn in prices, Kniveton said. Those that don’t will look to asset sales or outside equity. “Sorry not to paint a rosier picture, but the current times are tough to navigate.”

Survival strategies

The only investments to get a green light from Kniveton’s calculations would produce over 90 bins per acre and sell for $345 per bin.

That was a far-fetched scenario for the grower panelists who spoke after her.

“Ninety bins an acre as a target … that’s not how it works, that’s not sustainable,” said Shawn Tweedy, a partner in Chiawana Orchards in Pasco.

It’s unrealistic for most systems, said Jacob Klaus, an orchard manager for Gilbert Orchards of Yakima. Yes, you can grow 95 or 100 bins of small, poorly colored Galas, but that’s not the goal.

Instead, Tweedy counseled growers to “grow the right fruit as effectively as possible” by focusing on pruning and thinning to targeted crop loads. “There is no miracle in 70 bins an acre if the fruit size is off,” he said.

Klaus said it’s important to track costs on a block-by-block basis to make good decisions, and he cautioned against cutting corners to save money. “That’s a way to fall behind,” he said.

Fellow panelist Keith Oliver, orchard manager for Olsen Bros. of Prosser, shared several cost-cutting strategies he’s deploying, including forgoing formal training and branch tying; weeding and mowing less; skipping summer pruning in favor of asking thinning crews to rip out big shady shoots as they go; and, in mature blocks, reducing fertilizer that just encourages top growth and shade.

The overtime rule is the top challenge ahead for 2024, panelists said.

“We’re under a lot of pressure from the sales desk to produce the right fruit in the right size in the right grade. If Friday comes around and the guys are at 40 hours, but the Honeys need to get picked today? If you wait 48 hours, you are not delivering on the goal,” Tweedy said.

Given the cost of every H-2A bed, it’s worth calculating where the balance lies between bringing in more workers and paying some overtime, he added.

In closing, Matson, the moderator, asked the panelists what they would plant in 2024.

“If I had a good answer to that, we wouldn’t have hundreds of acres of open ground,” Oliver said.

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment