At a local Italian trade show 10 years ago, Walter Guerra displayed every managed apple variety he could find. He ended up with 30.

In November at Interpoma in Bolzano, South Tyrol, Italy, that number topped 60.

Displayed in glass cases and arranged in the shape of an apple, Guerra’s “Variety Garden” illustrated how heavily the world’s progressive apple-producing regions have bet on branding to stand out from commodity fruit.

“So, everywhere, people are asking, ‘Is it too much?’ or ‘Do we have the right varieties?’” said Guerra, head of the Institute for Fruit Growing and Viticulture at South Tyrol’s Laimburg Research Centre and one of the organizers of Interpoma, a global apple trade show. “We did this varietal exposition here just to animate a little bit of discussion.”

Not all those varieties will win this game, experts said, but not everyone is shooting at the same goal, either. Different regions breed for different traits, and markets have their own personalities and price structures.

Different places, different traits

For example, disease resistance is a priority in Europe, where regulations on chemical use are stricter than in the United States. Resistance is one of the first questions Kevin Brandt fields during license discussions.

“If I can’t provide that, they don’t have interest in moving forward,” said Brandt, vice president of Proprietary Variety Management in Yakima, Washington.

Trademarked European apples such as the French-bred Story and Italian-bred RedPop both are pitched as resistant to apple scab, a fungal disease common in humid climates of Europe, New York and Michigan. (A note to readers: In this story we identify varieties by their brand names rather than cultivar names to minimize confusion.)

Meanwhile, European consumer tastes skew toward traditional, tart and dense. Pink Lady is the top brand in Europe.

Also, Europe has many markets in many countries, said Steve Clement of Sage Fruit Co., a Central Washington marketing company, as he browsed new varieties on the Interpoma trade show floor.

The continent has giant retailers equivalent to Walmart or Costco, but it also has more produce stands, smaller stores and more overall diversity in shopping experiences, so there may be more room for more varieties, Clement said. “All these guys that have new varieties, I don’t think they’re going to every retailer in Europe with the same varieties,” he said.

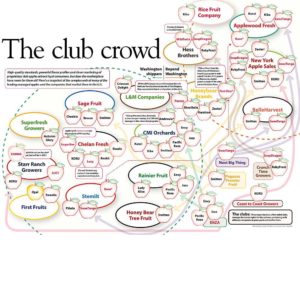

A lot of brands

As for the sheer number of brands, it doesn’t surprise Susan Brown, an apple breeder at New York’s Cornell University. Heterozygous apples “just want to be different,” resulting in many diverse, new offspring, said Brown, who presented about varieties at Interpoma.

Marketing is needed to help shoppers select from all those options on store shelves, said Brown and Tom Barnes, CEO of Category Partners, an Idaho-based U.S. consumer research company.

In America, branded varieties capture a larger share of the market each year and continue to grow in dollar sales — a 21 percent jump in 2022 — though overall apple consumption is still declining, according to Nielsen data. That means the increases in branded sales are not making up for the losses in the traditional varieties they displace, said Barnes, who also spoke at Interpoma.

The trick is finding a variety that stands out among a field of good — even great — ones, said Dave Gleason, a horticulturist for Domex Superfresh Growers in Central Washington. You either go niche or find something so appealing that the market will demand growers plant it, the way it has with Honeycrisp in America, he said.

“With present returns, the appetite for putting all the effort into a new variety is not high,” Gleason said.

Brandt of PVM agrees the field is crowded, but he believes the brands that consistently deliver on their quality claims and maintain ample volume will last.

“If you reach the consumer and the consumer desires the product, you want to have it on the shelf every time they come,” he said. “If they go to a different apple, there is a possibility you might not get them back.”

With the rise of proprietary varieties, production data becomes harder to parse out of volume totals. Guerra estimated that New Zealand and the Netherlands lead with about a 25–30 percent share in branded acreage, while others suspected those figures might be higher.

Desmond O’Rourke, a market analyst and retired Washington State University economist, stopped publishing his World Apple Review — a tally of both branded and traditional varieties for all countries except China — in 2018. The World Apple and Pear Association publishes stock reports and forecasts for Europe and the United States, with most brand names falling under a category labeled “other.”

To help U.S. growers make planting decisions, Christopher Gerlach of the U.S. Apple Association is tabulating what he calls the “Nursery Pipeline,” a region-by-region count of each variety in the ground, based on tree sales, going back to 2017. Also, members of USApple, a national trade association,

have asked him to begin including more proprietary cultivars — such as Envy or SweeTango — in the “other” category of the group’s monthly storage reports.

Italy and Europe

Italy is on the variety development bandwagon, and members of the International Fruit Tree Association toured two breeding facilities, as well as Interpoma, during their November visit.

Guerra of Laimburg estimates one of every six apples grown in Italy is a managed variety. In South Tyrol, one of Europe’s most progressive regions, that’s nearly one in every four apples, while the acreage of managed varieties has quadrupled in the past 10 years.

The volume and investment of club apples is growing but still small, said Marzio Zaccarini, technical area manager for the Italian Consortium of Nurseries near Ferrara, which bred the RedPop variety.

Solid figures are scarce even for him, Zaccarini said, but one count released by Prognosfruit, organizers of an annual fruit conference, estimated Cripps Pink and “new varieties” together accounted for about 6 percent of Europe’s production in 2022.

“It is an increasingly important niche market that today struggles to significantly increase the space on the shelves of retailers — also because of the exponential number of new apple clubs launched in the last 10 years,” Zaccarini said.

The consortium’s Variety Innovation Center, which IFTA toured, was founded in 1983 and focuses on strawberries but also has 5 million pear and apple trees and 8 million rootstocks for apples and pears on about 156 acres of sandy soil near the shores of the Adriatic Sea. The breeders test their selections in different planting densities, rootstocks and training systems at 44 private and public test sites around the world.

Genetic altering of produce is forbidden in Europe, though breeding centers track genetic markers to speed up their own research and development process. When making selections, environmental concerns, such as low CO2 emissions and few chemical inputs, are high in priority, as are grower and consumer benefits, Zaccarini said.

The goal of breeding and branding is not just to deliver something new but also to drive up quality for the entire industry, which — in theory — should drive up consumption, said Sage Fruit’s Clement. Production companies often research breeding programs as much as the varieties they offer, he said. The breeders who are their own worst critics often produce the best fruit.

“The (breeders) who look at all their selections and they try to find reasons not to do it, they tend to have the best selections, because they weed out more,” Clement said.

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment