In the heat waves of the future, shade netting may not do the trick.

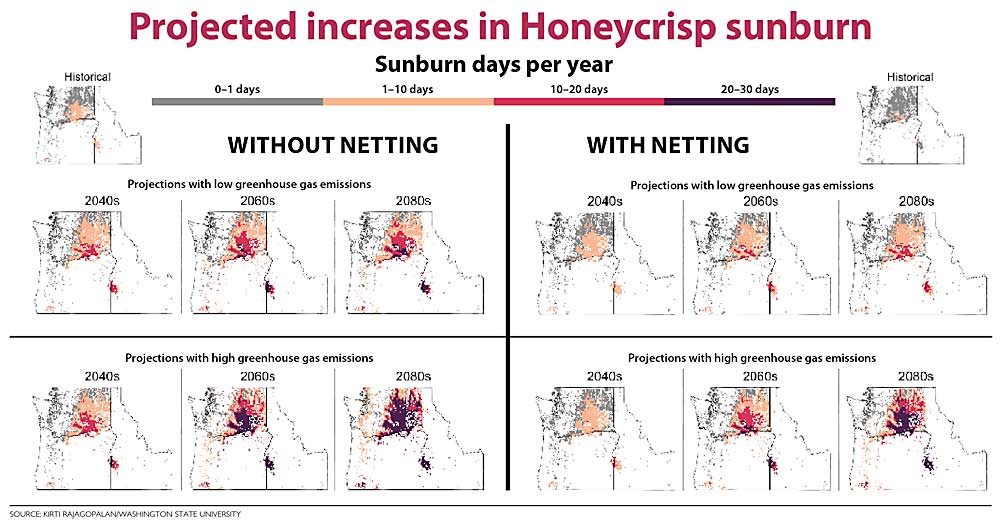

Washington State University climate models show temperatures rising well past the point that netting would protect apples from heat damage in the Pacific Northwest through the rest of the 21st century.

“Netting … worked quite well historically but not enough on its own, even in the near future,” said Kirti Rajagopalan, a biological systems engineer at WSU. Rajagopalan is collaborating on heat risk research with Lee Kalcsits, the endowed chair for tree fruit physiology and management.

Rajagopalan shared her projections with growers during a February webinar called “Feeling the Heat,” held by the Okanagan Horticultural Advisor’s Group. Other talks focused on apple storage implications of the heat, and a panel of growers shared how their farms fared in the heat.

Rajagopalan simulated 38 climate projections that estimated future sunburn days — days at which the temperature reaches a threshold that would cause sun damage — through the year 2100 in Washington, Oregon and Idaho.

The projections were based on two scenarios of atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations that drive climate change — one assuming some global policy changes that attempt to reduce emissions, the other assuming none. (As is common in the world of climate science.) She repeated them for Honeycrisp and Cripps Pink apple cultivars grown with or without shade netting.

All scenarios led to some sunburn days, even with netting over Cripps Pink, a relatively sun-tolerant variety compared to Honeycrisp. By midcentury, even the more optimistic scenarios showed Honeycrisp apples under shade nets experiencing double-digit sunburn risk days.

The projections assumed apples fully exposed to the sun, not those protected by the shade of the tree canopies, she said.

Throughout winter grower meetings and seminars, Kalcsits has been sharing a similar message about the limits of shade netting. Netting reduces incoming solar radiation but not necessarily air temperature. During the 2021 heat wave, some apples under shade netting suffered heat damage beyond the point of marketability.

He and Rajagopalan recommend growers plan multiple, overlapping strategies to mitigate heat.

Other researchers warned of extreme heat skewing normal ways of doing business, as well.

The 2021 heat wave threw off typical tree fruit maturity indices and made storage unpredictable, said Carolina Torres, WSU’s endowed chair for postharvest systems, in the same webinar.

For example, fruit firmness decreases in storage faster after a hot season than a cool season because apples enter the warehouse with a higher metabolism, she said. Research has demonstrated this for the past 15 to 20 years, including in observations Torres made in Chile where she followed the same group of trees for four years.

Hot weather also prompts growers to harvest early, which also can throw off maturity measurements, she said.

All the confusion leaves growers scratching their heads, she said, because they “don’t know what to do, when to harvest, what index to believe.”

Torres recommended paying close attention to multiple harvest maturity measurement tools, something the industry may do less of since the advent of 1-MCP, which slows ripening in storage, she said.

Growers are “maybe less concerned” about monitoring multiple harvest maturity indices than they used to be, she said.

Apple maturity indices — chlorophyll degradation, starch clearance and firmness — were developed in the 1950s, long before climate change and erratic seasonal temperature swings became a global topic. They are due for updates, she said.

The heat also causes more storage disorders, such as sunscald or stain, and lenticel breakdown, a peel-only pitting condition. Bruising also increases in the heat.

Seradaye Lean, a field service representative from Consolidated Fruit Packers in British Columbia, noticed some of the misaligned indices, she said during the webinar.

Galas experienced erratic starch clearing, she said. Sometimes, the apples had no starch clearing or sunburn, but they had lots of splitting. Her growers lost about half the Gala crop to the ground.

Lean saw an increase in early bitter pit in McIntosh apples, especially in the more vigorous, free-standing trees.

Ambrosia, however, proved resilient and “very impressive,” she said.

Growers sort-picked the best they could, but packers found sunscald in the warehouse. Few growers in the Okanagan Valley of British Columbia use shade netting, Lean said.

Lean said the company also had to communicate with customers more than usual. “We had to do some relationship building with our buyers to explain to them, ‘Yes, it was happening, but no, it’s not a complete disaster.’”

At Allan Bros., a Yakima Valley, Washington, producer, most apple orchards have a combination of netting and overhead cooling, especially Honeycrisp, said Matt Miles, a process improvement manager who works more in the warehouse than the orchards. Those fared well.

“Everything looked pretty good,” he said.

On the other hand, some cherry blocks — even those under netting — were complete losses.

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment