A well-engineered trellis system should support the maximum stresses expected from fruit load, wind or snow.

What about a tornado?

Ontario grower Tom Ferri has weathered two such extreme wind events in the past 12 years, sustaining damage to trees and trellis as well as his home and shop. The latest: Last fall, 85 mph winds hit the orchard with a few days remaining in harvest, destroying a quarter-acre of trees. But the experience hasn’t soured his perspective on his preferred training system.

“We have the right design for us,” he said during a panel on trellis engineering during the International Fruit Tree Association’s annual meeting, which was held virtually in February. He plants super spindle systems at 10 feet by 2 feet, or even 18 inches, supported by 12-foot-tall wood posts, pounded in 3 feet and spaced every 20 feet. “We like simplicity and we like strength,” he said.

Finding the right trellis system has been an evolution for many growers, occasionally involving trial and expensive error, said the panelists, which included Washington growers Travis Allan and Dale Goldy, along with Justin Finkler from Michigan and Ferri from Ontario. They shared their current favorite systems and thoughts on building now for the future.

“We need to maximize yield and quality and we need it to be suitable to current and future technology,” said Finkler, operations manager at Riveridge Produce of Sparta. He described the company’s evolution toward V-trellis with a seven-wire system.

“In 2014, we tried our hand at a V-trellis. This was a relatively large learning experience for us,” he said, recommending growers work with an engineer or trellis company. Now, that system is all they plant for apples.

While engineers can help growers design trellis for current needs, it’s important to consider how that could change over the life of the orchard, Goldy said.

“I want to make sure that everybody is thinking about what they are going to be producing in 15 to 20 years. We’re going to get better at what we do, and there’s going to be more fruit on those trees,” Goldy said. “We’ve all fixed whatever fell over last, but we didn’t do the 30 percent overengineering to allow for greater improvement.”

A math mindset

The engineer who spoke at the session, Mark De Kleine of TrellX, said he aims to make sure a trellis is neither under- nor overengineered.

“If you tried something and it didn’t work, you know it didn’t work; but if you overspent, you don’t know,” he said in an interview after the conference. “Engineers can help you use capital effectively. The strategy is to find that sweet spot.”

He walked IFTA attendees through the model for how his company measures the aboveground and belowground forces at play in an orchard system — wind loads and fruit loads versus soil, anchors and posts — to ensure the materials and selected design perform as intended.

There is no one right way or right material, he stressed. In fact, he’s rarely installed the same system twice.

Today, growers commonly find they can produce more fruit than expected when they planted the system, especially at the top.

“We’ve learned we could farm past the top wire and still get adequate light at the bottom of the tree, but that’s a huge challenge to the trellis. We were getting 75 bins an acre but only planned for 60,” Goldy said. “More production at the top means more leverage on the posts.”

For growers who want to go taller, De Kleine recommended they consider a retrofit with taller posts and treat it as a separate trellis system for the higher load. It’s easier to engineer the identified load structure of an addition than to bolt extensions onto an existing system that wasn’t designed for the extra load.

That’s why he encourages growers approaching trellis decisions to embrace math.

“Trellis needs to be understood by data points and numerical analysis,” he said. “If you don’t understand what I talked about, find someone who does.”

Allan echoed that sentiment.

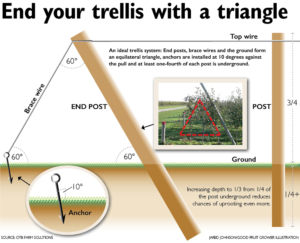

“Anchoring is the major problem with V-trellis. If the wire breaks, it’s all going to go down, so my advice to everybody is get your anchoring right,” he said. “Pay someone to help you engineer it, at least the first time.”

Tips and tools

In Washington’s dry climate, pounding in posts can be a real challenge. Allan shared an invention his team uses to solve that problem: a DIY water drill. Built from pipe pieces and attached to a Rears sprayer with water at 150 psi, it liquifies a narrow column of dirt with water pressure as it is pushed into the soil. Another worker then easily places the metal posts into the dirt, and they settle in tight, he said.

Goldy also used water to his advantage when planting a new ultrahigh-density block with 6-foot rows and 3.5-foot tree spacing. To hold up his expected 100-bin-an-acre yield, he set 10-foot posts every 21 feet, which means each should have a load of about 350 pounds. (In comparison, he said that in a 12-by-3 block with 36 feet between posts, each post was responsible for more than 700 pounds.) Prior to pounding in the posts with an excavator, he ran the drip tube so the dirt would be wet enough.

“By driving in these posts, the ground is almost completely undisturbed. This is the most solid trellis I’ve ever observed,” he said. “The last thing we did was plant the trees.”

Anchors attracted a particular focus in the session. Goldy recommended working with a trellis company such as TrellX in difficult ground because of the specialized equipment they have to set anchors. Finkler said that in every iteration of V-trellis Riveridge has planted, they’ve had to beef up the anchors. And Ferri recommended using 1/4-inch cable between the anchor and the wires to prevent rust and wear near the ground.

The panelists also advised keeping an eye out for signs of strain in the system — loose anchors, leaning rows, rusting wires and shredding wood on posts. Once a post starts shredding or is girdled by the wire, it’s not a 6-inch post anymore and can’t do the same amount of work it could when it was intact, De Kleine said. (To prevent wire from cutting into wood posts when under tension, he recommends putting staples into the wood before wrapping the wire, which creates a bigger surface area to spread the load.)

Ferri said that in his orchard, rotting posts appear to be the vulnerability that led to the recent tornado loss. A batch of posts he — and some neighbors — all purchased about a decade ago have had problems with rot at the soil surface, from insufficient treatment of the lumber.

“We’ve got to the point now that every spring we push against the posts and if it’s rotten, we replace it,” he said.

Allan said that as harvest nears, he looks at all the anchors as he drives through the orchards to see if anything appears to be loosening under the weight of the crop.

“Your anchors will give you a telltale sign. You can see where it’s dirty,” he said. “If it just looks a little off, you have to address it after harvest. It slips over time, so it will give you the signs before. Unless it’s a tornado, and then I don’t think anything is going to work.” •

—by Kate Prengaman

It is important to always ask the post suppliers if the posts are treated to CSA and AWPA standards for treated wood with ground contact. A properly treated post should last 25 years if it hasn’t been damaged during installation.