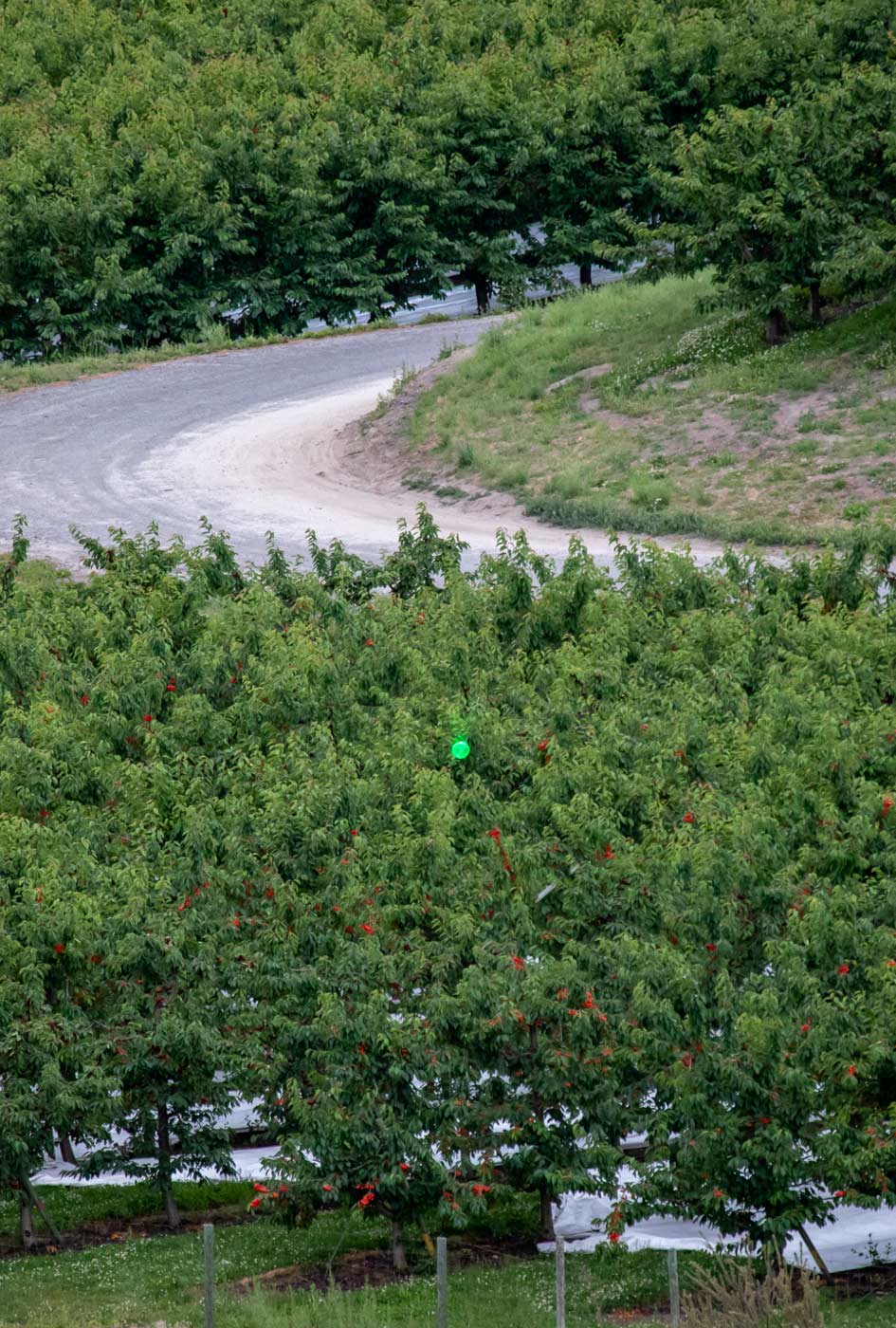

An orchard full of ripe cherries with nary a bird to be seen.

It was almost eerie, said Jeff Cleveringa, research and development director for Oneonta Starr Ranch. But that’s what happened last season when he installed an automated laser bird deterrent system for the first time in orchards along North Central Washington’s Lake Chelan, first in cherries and then in Honeycrisp.

“When it came time for Honeycrisp harvest, it was hard to find bird damage in the block. So, is it really that good or was it just the year?” Cleveringa asked, as his second season with the technology was about to start. “If it’s really that good, we’re going to be buying quite a few more.”

The laser system, developed by Bird Control Group, a Danish company, is one of several new technology options for growers that promise to prevent the common flaw in many other bird deterrents: habituation.

Bird damage costs growers of high-value fruit crops millions every year. A 2012 study put the toll at $49 million for California’s wine grape industry, $32 million and $26 million for Washington’s cherry and Honeycrisp crops, respectively, and $14 million for Michigan blueberries. The most common bird control strategies on fruit farms are auditory or visual scare devices — each used by about half the of the cherry, blueberry, wine grape and Honeycrisp growers surveyed in 2012.

But most growers also reported that such tactics were only slightly effective at controlling bird damage to their crops. That’s because over time, birds tend to become accustomed to fake predator calls or startling sounds.

“Birds are pretty smart, and they quickly learn that it doesn’t have a real threat behind it,” said John Swaddle, a professor of biology at the College of William and Mary who studies the impact of noise pollution on wild birds.

Noise nets

Unlike fake predator calls, noise pollution presents a real threat to birds because they can’t communicate with each other or listen for real predators in their environment.

So, Swaddle and a colleague in the applied science department, Mark Hinders, decided to investigate if constant, interfering noise could be used to keep birds out of unwanted places, like airports or farm fields. Pilot tests proved it was effective at displacing nearly 90 percent of birds; the technology, now known as Sonic Nets, is being tested in orchards, industrial facilities and a U.S. military base.

“It’s taking a bird’s point of view of the issue. You are fundamentally stopping birds from being able to hear and live their normal lives,” Swaddle said. “Yet there is always a real predatory threat in the natural environment, so they don’t habituate to this.”

The challenge is that it takes a large, solar-powered speaker system to project this noise across farms, and that gets expensive. MidStream Technology, which licensed the idea from the William and Mary researchers, has spent the past few years trying to reduce manufacturing costs and boost the sound production the solar power systems are capable of generating.

Right now, speaker systems cost $3,500 and can cover about 5 acres, said Steve Rehberg, a consultant in the Northwest with Flock Free, a New Jersey-based bird control company that holds the U.S. license for the technology.

“It’s the most valuable tool we have,” Rehberg said. “I still don’t think we’re 100 percent where we need to be on the hardware side, but the technology works. It’s really a matter of scaling it so it’s affordable to growers.”

With the option to use parametric speakers, which push sound in just one direction, the technology will be able protect an orchard without annoying neighbors on one side.

“It makes perfect sense for high-value crops in small acreage,” said MidStream CEO Sam McClintock, but he acknowledged that the technology has gotten off to a slow start because “a lot of the market is very suspicious because past solutions have failed.”

Columbia Basin cherry grower Rich Callahan decided to give the technology a try this year. “We’ve tried everything else already,” he said about his Chelan orchard near Othello. “We had to do something. I’ve got the first fruit that’s ripe around here and the birds just know.”

The speakers, which make a noise Callahan describes as like an old TV that lost its signal, seemed to be keeping the birds away when Good Fruit Grower visited about a week before harvest. Birds nesting in a nearby clump of Russian Olive didn’t fly into the block, and Callahan is optimistic.

“So far, it really looks like it’s working,” he said. After cherry harvest, he planned to move the systems to his Wildfire Gala and early Honeycrisp, which also ripen early and draw heavy bird predation.

Close to the speakers, the sound is annoying to humans as well as birds. Callahan said he plans to shut the system down during harvest, since the presence of the picking crew will deter birds as well. Upcoming research at the University of Idaho will explore the capability of the speaker systems to deter deer and elk as well, Rehberg said.

At the moment, fewer than a dozen growers have bought the technology, he said, and the big users are in the industrial sector where it’s easier to plug in and power the speakers. But they hope to increase production and dealer capacity for the agricultural sector soon, Rehberg added. “The limitation on this is how many we’ve been able to produce; not how many people want them.”

Automated lasers

Along Lake Chelan, neighbors’ complaints about conventional bird deterrents, “stuff that starts screaming and squawking at 5 a.m.,” motivated Starr Ranches to try another option, Cleveringa said. They noticed the effect right away.

“When you start it up, the robins just go crazy. There’s movement in the block and they don’t like it,” he said.

A laser is emitted from a device mounted to a motor that moves the beam in a programed pattern of targets across the block. The beam itself can stretch for miles, but to keep birds out of the orchard requires it to regularly patrol the space.

“Originally we were a laser company, and we saw an opportunity to develop a light beam specifically for bird control,” said Steinar Henskes, the CEO of the Bird Control Group. Development of the robotics and software needed for the laser to track the orchard automatically followed, and now the company has more than 6,000 customers from growers to airports in 76 countries.

Birds perceive the light beam as a physical threat because it constantly moves across the orchard in a sweeping pattern. “How it moves is like a physical object that patrols the area,” Henskes said. “It causes flocks to move away and it scares off scout birds from even approaching the area.”

Currently, the autonomous laser system is available in the Pacific Northwest from Oregon Vineyard Supply, at a cost of $9,495 for the latest model, the Autonomic 500, said Wayne Ackermann, a crop consultant who recently left OVS to start working for the Bird Control Group. Accessories, such as solar panels or mounting equipment can add hundreds more.

Last summer, OVS leased 15 units to Oregon blueberry growers, with an option to buy at the end of the season if they liked the technology; 14 bought them, Ackermann said.

“It works, it’s affordable, and it’s neighbor-friendly,” he said. As a rule of thumb, one unit can cover about 20 acres, but topography makes a big difference. It’s easier to get good coverage in a flat blueberry field than a hilly vineyard, he said, but strategically overlapping the systems can also increase effectiveness.

In coming years, Bird Control Group wants to partner with ag service providers to rent the system to growers for only as long as they need it, so growers will always have access to the latest upgrades to the technology, including soon-to-be-released wireless connection and security camera features, Ackerman said.

“We want to operate like a subscription for your bird deterrence,” Henskes said. “They only have problems for two or three months a year, so it makes sense for them to lease the machines from us. So, we’re building a network of installation partners.”

Right now, the downside to the technology is that it’s not very user friendly, Cleveringa said. “It’s an expensive tool, and you want to make sure you can utilize it, and that takes time and effort,” he said. More service providers in the region familiar with the system will help, and setting up that network is part of Ackermann’s new job with the company.

Both the laser and speaker technology cost considerably more than most growers are used to paying for bird control. But, if they prove themselves in orchards where bird damage is high, the cost may pencil out pretty quickly.

“It doesn’t take very many Honeycrisp to make $10,000 back for your ranch,” Cleveringa said. •

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment