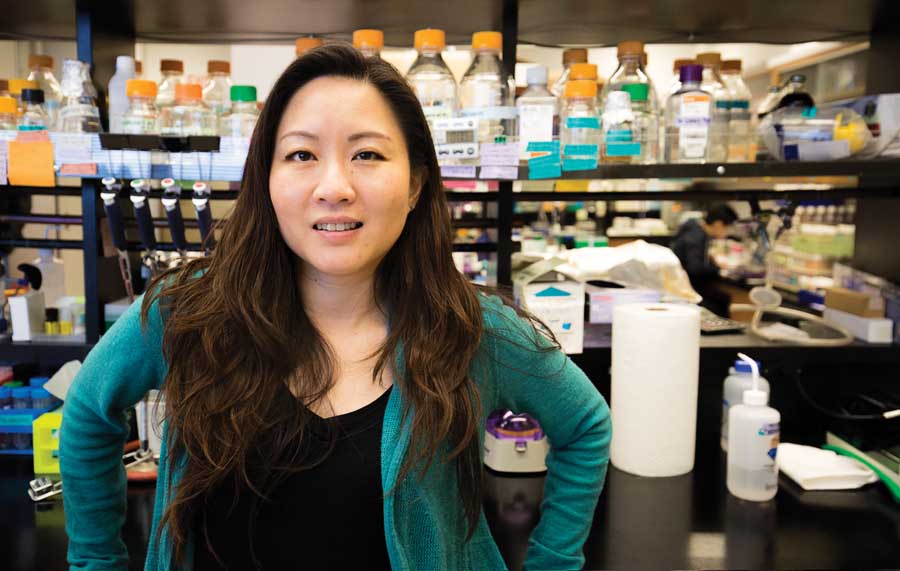

Dr. Joanna Chiu of the University of California, Davis, has published research on yeast biopesticide to be used on spotted wing drosophila. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

Using genetically modified yeast as a biological pesticide. Deciphering olfactory signals for better baits. And engineering chromosomes to allow for only male offspring.

Some of the latest research ideas to control the dreaded spotted wing drosophila in California sound like science fiction, as scientists look for alternatives to conventional insecticides and traditional approaches.

“We’re trying to be creative,” said Dr. Joanna Chiu, an entomologist at University of California, Davis.

The alternative is to keep spraying harsh pesticides that throw everything else about integrated pest management (IPM) out of whack. Besides, spotted wing drosophila will eventually develop resistance to chemicals, just like most insects do.

“The real problem is the recognition that we can’t keep spraying these things into oblivion,” said Greg Costa, a Lodi, California, grower and packer and chairman of the research committee of the assessment funded California Cherry Board.

In 2015 and 2016, the research committee spent a combined $381,000 – 66 percent of the two years’ budgets — on a wide array of projects related to control of spotted wing drosophila.

“We don’t want to rely on one strategy,” Costa said.

Among them:

—$173,000 toward efforts by Dr. Bruce Hay of California Institute of Technology and Dr. Omar Akbari of the University of California, Riverside, to genetically alter SWD that breed only males and would then knock down the population when released into the wild. They started in 2013. The project builds on Hay’s work with fruit fly RNA replacement that was named as one of the top 50 advancements by Scientific American in 2007.

—$49,000 to Dr. Kent Daane at the University of California, Berkeley, to find new biological controls for the flies, specifically a larval parasitoid from Korea.

—$310,000 toward deciphering the olfactory signals and reception in drosophila-yeast communication for Dr. Zain Syed at the University of Notre Dame. Some of his results were published in September 2015 in Scientific Reports, an academic journal of the Nature publishing group. Syed is scheduled to begin field trials this year of his findings to develop better attractants to use in traps, Costa said.

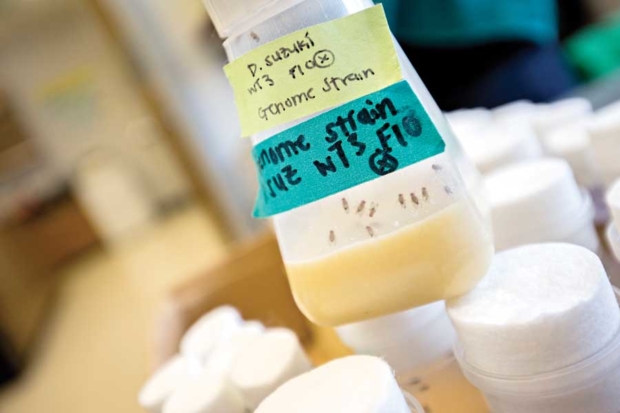

D. Suzuki genome strain sample in Chiu’s lab in Davis, Calf., on March 7, 2016. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

Then, there is Chiu, an entomologist who normally specializes in the circadian clocks of animals as part of human medical research. She also collaborated with Oregon State University researchers to sequence the genome of the spotted wing drosophila in 2013.

California cherry growers spent about $40,000 for a two-year project that ended last year that allowed her to develop yeast strains that could slow down the reproductive activities of flies that eat it.

The altered yeast delivers tweaked strands of RNA to the drosophila that tricks the pest’s immune system to attack its own endogenous RNA critical to survival. The concoction reduced larval survivorship, their ability to move and their reproductive fitness, according to her research paper published in early March, also in Scientific Reports.

Using RNA interference to manage a pest is nothing new. It has worked in aphids, termites and mosquitos. Delivery is usually the problem. Fortunately, drosophila love yeast, which occurs naturally on the surfaces of fruit.

When Chiu fed larvae her modified yeast, fewer of them made it to adulthood. When adult flies ate the yeast for three days, they all lived but reduced their activity level for several days, recovering after five or six. However, the females laid fewer eggs and fewer of those eggs made it from larvae to adults.

The news was good, but Chiu hopes to target different strands of RNA that will prove even more fatal to the spotted wing.

“It’s not dying enough,” she said with a smile, gently pounding her fist on her desk. “It’s dying, but not enough.”

However, one of the best parts was the yeast only caused ill effects in spotted wing drosophila and none of its closely related cousins, which means the method can conceivably be used to target only the invasive pest, not an innocuous or beneficial native bug.

That may help her and her grower-benefactors with one potential drawback of her proposed control method — public perception.

“This is a very risky idea,” Chiu said.

The term “genetically modified” carries baggage in the eyes of consumers. To be safe, she and other researchers are trying to build genetic “on-off” switches into their methods, such as a specific nutrient in the yeast. They don’t want uncontrollable Frankenbugs released into the environment either.

The growers on California’s research committee haven’t tried to address public opinion yet. They first want to let researchers develop some technology and build funding partnerships with other commodity groups.

But they believe the public will come around, pointing to favorable opinion of using genetics to breed diseases out of mosquitoes, for example, and comments from none other than Bill Nye, the “Science Guy” author who made waves last year for softening his stance against genetically modified organisms in July.

Besides, public perception isn’t fond of heavy chemical spray programs either.

“It won’t work, it’s too expensive and it’s anti-public also,” said Rich Handel, a member of the research committee since the early 1980s and a former chair. “You know, there’s just as much concern about spraying as there is GMOs.”

Spotted wing drosophila has gobbled up most of the extra research funding of the California Cherry Board in recent years.

Growers on the committee consider funding research a bargain to the alternative of continued spraying, which cost $50 per acre or more three to five times per year, said Arnie Toso, a grower and member of the National Cherry Growers and Industries Foundation, a voluntary membership group based in Hood River, Oregon, that represents cherry growers.

“This research then becomes, in my opinion, peanuts,” he said. •

– by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment