In the predawn hours of July 2020, a fleet of blueberry picking machines rumbled at 0.2 miles per hour through a field near Yakima, Washington. The tines of the picking cylinders grabbed the bushes, parted them in two and bent each half sideways, gyrating the berries loose and onto catch plates before trucks hauled them to the Roy Farms warehouse for fresh clamshell packaging.

With surging global volumes of blueberries, high demand for fresh fruit and rising labor costs, growers want machines to harvest for the fresh market — a task that, until recently, was reserved solely for nimble human hands now in short supply.

“The sheer number of people it takes to pull blueberries off the plant is astronomical,” said Michael Roy, CEO of Roy Farms. “It’s just not sustainable.” At peak harvest volume on mature bushes, one mechanical picker with a crew of four does the work of as many as 80 hand laborers, Roy said.

Equipment manufacturers across the globe are searching for new ways to handle the tender fruit gently, from softened catch plates and brushes to angled surfaces and air blasters.

“Everyone is trying to do this thing,” said Andrew Herr of Littau Harvester, a Stayton, Oregon, equipment manufacturer.

Of Washington’s 40 million pounds of fresh blueberries, machines picked between 5 million and 8 million in 2020, according to the Washington Blueberry Commission. In Oregon, which produces 75 million pounds of fresh berries, the machine-picked share is larger. Washington has produced more berries overall than Oregon has in recent years, but Washington has a higher percentage of volume going to the processed market. However, machine-picked fresh volume is increasing in both states every year. Northwest growers now plant more varieties that lend themselves to machine harvest, such as Calypso, Duke and Draper.

The technology race marks a pivot point for the blueberry industry, said Kasey Cronquist, president of the U.S. Highbush Blueberry Council in Folsom, California. For 20 years, the health benefits of blueberries drove a surge of awareness. Now, everybody knows about blueberries, so the industry needs to scale up.

“Innovating the blueberry industry is the next era,” Cronquist said.

Even berry giant Driscoll’s, which boasts of hand-picked fruit in its branding, accepts a small amount of machine-picked berries for fresh distribution, said Frances Dillard, vice president for brand and product marketing for the Watsonville, California, company.

Machine harvesters also are selling in Latin American countries, where labor is relatively cheap, just to keep up with the size of new plantations. “The scale of what they’re doing down there is almost mind-boggling,” said Kathryn Van Weerdhuizen, grape and berry market manager for Oxbo International, an equipment manufacturer in Lynden, Washington.

Roy Farms and A&B

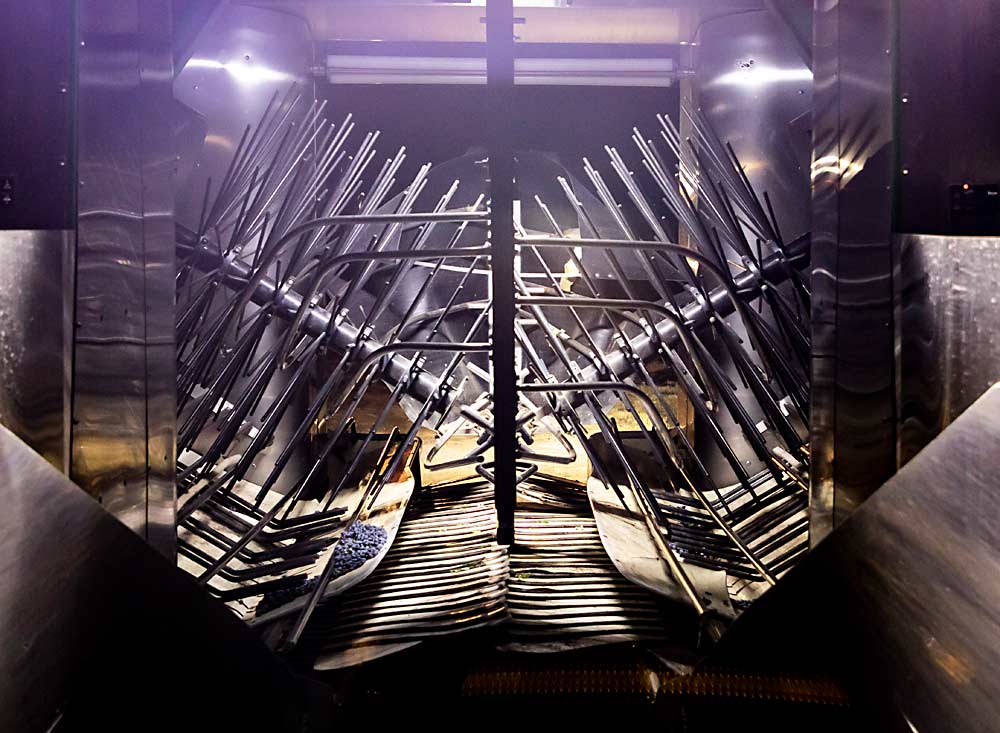

In 2018, Roy Farms opted for Fulcrum harvesters, developed by A&B Packing Equipment in Lawrence, Michigan. The machines have picking cylinders that can be tilted to lay bushes sideways, what the company calls a “horizontal picking position.” The idea is to reduce the drop distance and therefore the shock to the tender fruit.

A&B Packing has a relatively small share of the blueberry picker market, but Roy Farms is one of the largest growers in the nation. The company has its own blueberry fields in Moxee, near Yakima, and is the managing partner for Othello Blueberry, a massive organic plantation located about 70 miles to the east and backed by a California investment group.

The two together will eventually reach nearly 1,800 acres. Long-term goals for both farms include harvesting by machine for the fresh market, though they are still running trials.

The Fulcrum’s horizontal approach results in less center drop, said Mario Aello, the agronomy and applied research manager for blueberries and apples at Roy Farms.

But there are trade-offs, he said. His crews lose efficiency with lug-stacking wagons off to the side of the machine, rather than the overhead platform used by other manufacturers. Meanwhile, the splitting action can be hard on the bushes. The company expects to break some canes, and instructs pruners to remove them, but has never had to replant, Aello said.

The machine also requires specific horticultural techniques, said Michael Williamson, CEO of A&B Packing. For one, trellises won’t work. Plants must grow as a bush, with limbs allowed to bend under the weight of ripening fruit.

The Fulcrum launched commercially six years ago, inspired by the experience of Williamson and his father, Robert, longtime blueberry growers who have used a variety of harvesters. The goal was to help Michigan berry growers stay in business.

“It was an invention out of necessity,” he said.

Other players

Aello warned against generalizing Roy Farms’ experience. All growers use different methods, he said. In fact, Roy Farms has also leased a few Kokan air jet berry harvesters, which use air to dislodge berries.

The Kokan, made by BSK of Serbia, skips harvest cylinders altogether, using blasts of air at a variable velocity and frequency to remove ripe berries that then drop onto air-filled, rubber-coated “pillows” instead of hard catch plates. Roy Farms is running trials at both of its locations, but Aello expects the air blast harvesters to perform better in Othello, where canopies are narrower and bushes are younger.

Most damage happens when rods move through the canopy, said Gregg Marrs, owner of Blueline Equipment of Yakima, the North American distributor for the Kokan. The air approach avoids that. The company has sold about 15 units to farmers in Florida, Georgia, California, Oregon and Washington since it began importing them in the summer of 2020.

Littau Harvester of Oregon has devised new shaker heads, called True Orbit, that twirl their tines in a circular motion, sending energy through the branches but with less shock than from a back-and-forth movement — much like stirring a pot of water in a circle makes a smooth swirl but wiggling back and forth causes splashing, Herr said.

The company focuses on the plant, too, Herr said. Research shows that combinations of boron and gypsum help keep berries firm. In 2019, the company tested nutrient treatments at its own research and development farm in Stayton and achieved higher packouts regardless of the machine they used. The company has contributed a harvester to Oregon State University, where researchers work on breeding smaller, firmer berries, and has also experimented with bush spacing to give catch plates — sometimes called fish scales — time to close around the base of the plants and reduce loss.

Herr recommends that anyone planting berries should plan around their intended harvester.

A new player in the harvester game is FineField of the Netherlands, founded in 2018. On its Harvy series, the company uses bendable brushes to catch berries. Its largest unit designed for fully automated harvest, the Harvy 500, has shaker heads that can be removed to morph into a harvest-assist machine that would allow workers to ride, pick and drop berries onto the soft brushes leading to a conveyor system of lugs and crates.

When the company started, they wanted to reinvent blueberry pickers, not just modify them, said Marcel Beelen, co-owner.

“We started with a clean sheet, and we started by saying: ‘No bruising, no losing,’” Beelen said.

FineField tested the Harvy 500 in Europe in 2020 and plans commercial trials in British Columbia this year with Dean Maerz of Klaassen Farms, also the company’s North American sales representative. The company’s goal is to make the machines available by fall this year, Beelen said.

In Washington, Oxbo has been collaborating with researchers from several universities and the U.S. Department of Agriculture to develop soft catch surfaces on machines, as well as study harvest timing and intervals. After a few years of trials, they found the softer surfaces improved packout and reduced bruised fruit over traditional machines, mostly unmodified Oxbo and Littau harvesters, but still fell behind hand picking, according to Washington State University data.

The company has begun selling its commercial SoftSurface kits that use a suspended surface, not a padded one. They work best on new machines but will fit some existing models, Van Weerdhuizen said.

Oxbo has chosen to take development slowly, she said. The industry needs to adjust varieties, timing of harvest and horticultural practices to make mechanical harvest viable, she said, and the innovation race will help everyone.

“It’s good for the industry when a bunch of different people are working on different things,” Van Weerdhuizen said.

Machine vs. machine

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment