Editor’s note: When the print version of this story was published in our March 1 issue, growers and industry representatives were awaiting 2021 survey results to decide whether to move quarantine boundaries again. This story has been updated to report the boundaries will remain unchanged in 2022.

Researchers in Washington suspect parasitic wasps may offer biological control for apple maggot.

Joshua Milnes, a Washington State Department of Agriculture entomologist, and his colleagues have been noticing a tiny wasp that typically parasitizes snowberry fly puparia is attacking apple maggot puparia, as well.

“That’s an exciting little discovery,” Milnes said.

He made the promising finding as part of the WSDA’s increased sampling for apple maggot larvae in wild hawthorn fruit and other native hosts, such as snowberry — an effort driven by recent detections in Okanogan County that suggest the apple maggot is extending its season.

That’s the good news, but the detections could require a quarantine shift in Okanogan County, the state’s northernmost production region, which would create extra hurdles for growers and packers moving fruit.

The quarantine

Apple maggot has been in Washington since the 1980s and has been steadily spreading throughout the state. It has never been found in an Eastern Washington commercial apple orchard, but WSDA regulators quarantine for the pest through a program funded by industry assessments, redrawing boundaries as it spreads.

Currently, the bulk of Okanogan County’s commercial orchards are in a “pest-free area,” a quasi-legal term that makes fruit transport smoother and cheaper. But in 2020, state surveys caught reproducing populations in two spots behind those lines. In response, the Tri-County Pest Board of Okanogan, Chelan and Douglas counties cut down hawthorn trees, treated stumps with herbicide and sprayed insecticide near the two hot spots. Industry leaders decided to leave the boundary as-is for 2022 while they consider changes for 2023.

Commercial growers in quarantined areas may still grow and sell apples but must have a WSDA inspection of harvested fruit or cold-treat fruit before transporting over the boundary line. Some foreign export markets require both measures, or fumigation. Those hurdles could cause a market disadvantage in Okanogan County, home to only one apple packing facility and one receiving warehouse.

“This could be a logistical nightmare,” said Rick DeLap, a grower near the town of Malott and president of the Okanogan County Horticultural Association.

DeLap is also concerned growers will shoulder the extra cost for packers having to sort fruit separately.

The uncertainty comes at a time of transition for the Apple Maggot Working Group, a loosely organized coalition of industry representatives and state and local pest authorities that decides where boundaries lie. Mike Willett, the former manager of the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission, used to convene meetings, but he retired in 2019. Meanwhile, the longtime pest agent for Okanogan County, Dan McCarthy, retired last year, and the county combined control efforts with neighboring Chelan and Douglas counties.

McCarthy, who still grows apples in the region, is concerned that Okanogan County’s location will lead to testing delays if the whole county is quarantined.

“When everybody’s getting ready to pick at the same time, how are they going to get around to everybody?” McCarthy said.

Regulators don’t have to quarantine the entire county though. Partial county quarantines based on rivers, mountains or other geographic features are common. In 2018, the western part of Okanogan County was put under quarantine after the pest was found in hawthorn fruit in the Methow Valley. Not too long before that, infestations in areas near Leavenworth prompted part of Chelan County to be quarantined. Yakima, Kittitas and Lincoln counties also have partial quarantines.

Even if the whole county is quarantined, the impact likely will be smaller than growers fear, said Bill Walker, Northwest regional manager of the WSDA’s fruit and vegetable inspection program. The agency already surveys that area for apple maggot: It surveys some 14,000 test sites in Eastern Washington, both inside and outside quarantines. Also, staff can move from one location to another to speed things up, said Mike Bush, manager of the WSDA’s apple maggot program.

Research

Apple maggot females lay eggs, sometimes by the hundreds, just under the skins of apples, causing pitted and misshapen fruit that starts to decompose where larvae feed. The puparia, which are pupae in the final larval stage that develops under a hardened exoskeleton, overwinter underground and emerge as adults the following year.

In Eastern Washington, the pest has been found only in native hawthorn berries, not apple trees.

“I’ve yet to see an apple maggot in even a backyard apple tree,” said Will Carpenter, the new pest agent for the Tri-County Pest Board.

Same goes for the recent Okanogan County find.

However, this one is a little different, Bush said. In the past few years, surveys have found adult flies in hawthorn later in the season, a shift in the apple maggot’s behavior. The late-season detections leave less time for WSDA to inform local pest and disease boards to take eradication measures and for the WSDA’s fruit and vegetable program to perform in-field inspections.

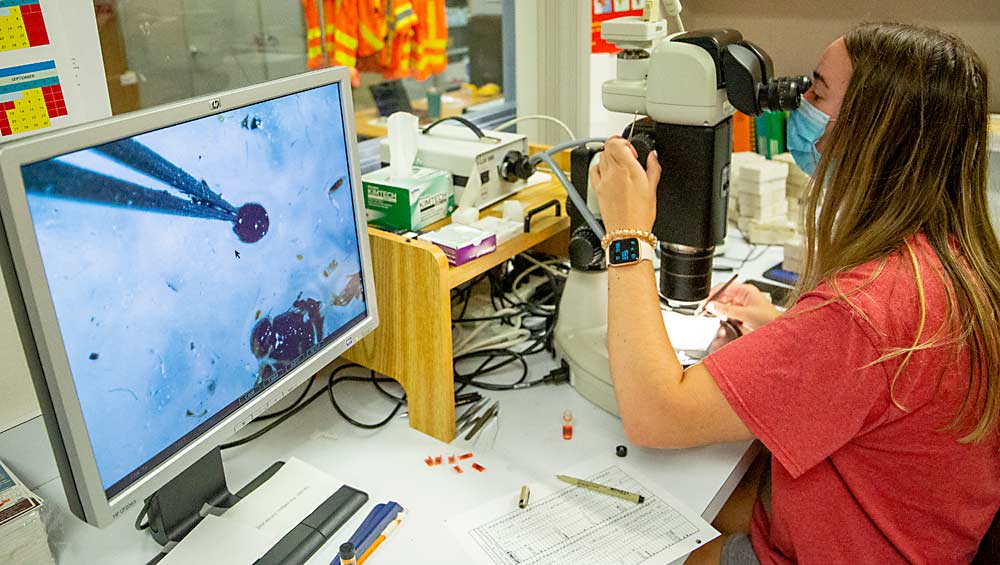

In spring 2020, WSDA hired Milnes, the entomologist, to help answer this late-season riddle. Since then, the agency and its collaborators have collected more samples of hawthorn fruit and increased the frequency of rearing larvae into adults. Apple maggot larvae look similar to those of other fly species.

The apple maggot fly and snowberry fly both evolved from the hawthorn fly in a process called sympatric speciation. Hawthorn is a native bush with “berries” that are actually small pome fruit that host apple maggot.

It’s possible the parasitic wasps are following the same adaptive path as their hosts, Milnes said. That would mean snowberry — another native plant — could be planted to attract the wasp as an apple maggot predator. He has the same theory about other native plant relatives, such as wild roses.

To test the hypothesis, Milnes and his team are collecting fruit samples from native plants and looking for flies and the wasps that parasitize them. Collaborators in the Eastern U.S. apple growing regions, where the apple maggot is native, are tracking similar connections to apple maggot.

Together, scientists in the apple maggot program have hypothesized that North Central Washington is home to a species of hawthorn that bears fruit later in the season. They aim to publish those findings soon.

The extra sampling of hawthorn, however, led Milnes to notice the wasps, which could become an ally.

“If we could prove that, that would be amazing,” Milnes said.

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment