Two-leader trees help to keep high-density planting costs down, but they take more time and care to grow into production and raise obvious questions. How do you keep the growing leaders in balance? Is the trade-off worth it?

“I was hoping that someone here would tell me,” said grower Ken Denbok, to members of the International Fruit Tree Association checking out his second-leaf, twin-leader Gala block in Collingwood, Ontario.

“There’s a lot more thinking involved in the first two years with these,” he said, referring to the baby trees he grew himself — heading back in the first year to create the twin leaders — compared to his usual super spindle system.

The friendly debate that followed was a hallmark of the IFTA 2019 Summer Study Tour, as 140 or so attendees visited farms across Ontario, where apple growers are searching through trial, and some error, to find better ways to strike a profitable balance between yield and fruit quality.

Innovative systems, from Italian imports to V-trellis, played the star role in the tour through one of Eastern Canada’s fruit-growing regions.

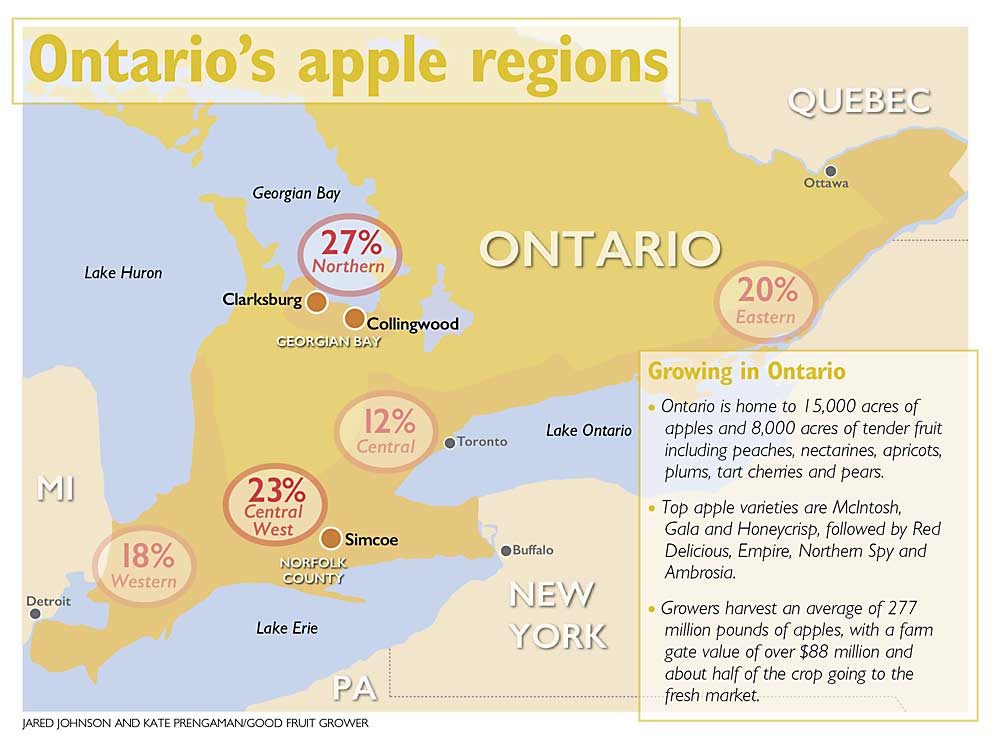

Much of Ontario is bordered by Great Lakes, and its fruit farms are found along their shores, taking advantage of the moderating temperatures, in five different production regions.

The tour focused on the top two: the Georgian Bay region, the province’s leading apple region; and Norfolk County, north of Lake Erie, where apples and tender fruit are grown.

Today, the province is home to 15,000 acres of apples and another 8,000 acres of tender fruit. As the region shifts into more fresh market apple production, traditional varieties such as McIntosh, Northern Spy and Empire are coming out fast, with new plantings of Ambrosia, Honeycrisp and Gala in their wake.

Ontario growers have the advantage of being the backyard for Toronto, one of North America’s largest and most diverse cities. Residents there buy a lot of fruit and want to buy local, although the region remains a net importer of fruit, so there is room to grow, said Steve Bamford, owner of Bamford Produce, a long-standing Toronto-based produce company that recently invested in an apple packing facility and orchards in the Georgian Bay region.

“As a marketer, we need to get good-quality colored fruit. Our customers are demanding good-looking fruit,” he said. “The packout numbers and the financial model when you have that yellow Honey are not good.”

Finding systems that consistently deliver high-quality, well-colored fruit is the goal for growers experimenting with new approaches. Bamford Farms is planting at 10 feet by 2.5 feet, with the aim of being automation-ready, he said, another common theme on the tour.

Norfolk County

In Norfolk County, grower Chris Hedges prefers to grow in a tall spindle system with trees about 11 feet by 2.5 or 3 feet, he said. The first-generation apple farmer got his start when his parents retired and bought a home with an orchard, but when the group toured a 100-acre orchard he bought in 2015, he said he will never buy an existing orchard again.

“It is too expensive to transition existing blocks,” especially when it comes to training staff and operating equipment on unfamiliar systems, Hedges said. “This block had a lot of big trees, big wood that had to come out.”

He sought the group’s opinion on managing vigor in a block of Honeycrisp planted on Geneva 41 rootstocks in 2015. His goal is to get 1,000 bushels an acre, or about 45 bins, which would be about 65 to 70 apples per tree, a pretty typical target in the region.

“I’m a B.9 guy,” Hedges said, adding that about 80 percent of his trees are on Budagovsky 9 rootstocks, which he credits with preventing fire blight issues. But the low-vigor rootstock takes time to push Honeycrisp to fill the space. Not so with G.41.

“I got so worried about growing these trees to the top wire we ignored the big stuff lower,” he said. Now, he’s adopted an aggressive pruning strategy, but it’s still not enough. “These trees have grown like crazy since the day they were planted.”

At a nearby orchard owned by Lingwood Farms, grower Murray Porteous shared the success story — so far — of a third-leaf Gala and Ambrosia block planted in the tall spindle tip system developed at Wafler Farms in New York.

Seeing the system on a previous IFTA tour in New York inspired his son to try the system, Porteous said, although his son has now decided against joining the family business.

The system was planted with rows alternating 8-foot and 13-foot spacing, angled out 16 inches, with in-row spacing at 42 inches for Gala and 40 inches for Ambrosia.

“We have really aggressive soil and 7 feet made me really nervous, so we went 8 feet, plus I didn’t want to buy any special equipment for just 35 acres,” he said, but they moved the trees 2 inches closer in-row to get the same tree-per-acre density as at Wafler’s.

“We wanted higher density but more room for picking,” Porteous said. “For us here, this is as good as it gets.”

The trellis has two wires, at 5.5 feet and 10 feet, and trees are trained vertically, each wrapped into a wire. They hedge the canopy, but only when there’s no active fire blight, Porteous said.

The system has proven sturdy, with not a single tree lost when a tornado hit last season, although most of the second-leaf crop was lost to hail damage during the storm. This year, it will crop about 340 bushels per acre.

“It’s designed to be picked with a platform, so the wider rows should be vertical when the trees have filled their space and the narrow rows will be on the angle,” Porteous said. “We don’t take any equipment other than a mower and weed sprayer down the narrow row.”

Not everyone is embracing high density, however. At Schuyler Farms, Brett Schuyler explained the thinking behind a new block of Honeycrisp planted at 15 feet by 6 feet on Vineland 1 rootstocks, which produce a semidwarf freestanding tree.

“We’re afraid of the really dwarfing rootstocks here on sand,” he said, adding that most of the farm is tart cherries, which love the sandy ridge soil. The decision to go freestanding was based on balance between the upfront cost and the time to get into production, plus, “I just like managing a freestanding tree,” he said.

Georgian Bay

In the Georgian Bay, in the hilly country north of Norfolk County, Denbok agreed. “If you want production in the Georgian Bay, that’s how we get it,” he said, gesturing to an older block of standard trees. Yields are good, but the fruit quality doesn’t make the fresh-market cut.

High-density Honeycrisp on his farm yield 37 bins per acre of fancy fruit on average, he said. But it’s hard to pay off a $50,000-an-acre investment in new plantings, which is why Denbok started experimenting with the two-leader system in 2015, planting Gala at 12 feet by 3 feet.

He discussed the pros and cons he’s discovered with the system the past few years, along with others in the group with multileader experience.

As the trees mature, balance between the leaders becomes less of a concern, and once the trees get established, they offer the major advantage of simplicity of pruning, said Tim Welsh of Columbia Fruit Packers. Denbok agreed.

“It’s the simplest way to prune. It’s flat, cut it in half; if it’s on a 45, get rid of it; if it’s over a third the size of the leader, stump it three fingers,” Denbok said. “Forget the mechanical harvester. I want someone to make a robotic pruner for us up here in the North. Simple. I can give it five rules: Don’t cut my wire, don’t cut my clips, and the three rules I just said, and I can cut two men off my program.”

But the question on everyone’s mind was: Does it really save money?

Denbok said he’s still compiling that data now that his first two-leader plantings are coming into production. Dale Goldy of Gold Crown Nursery said that because you lose a year to head and split the trees, that lost year of production tends to outweigh the tree savings, especially because those establishment years are not cost-free.

The decision to go multileader or plant at higher density really comes down to your capacity to execute, said Karen Lewis, Washington State University extension specialist.

At Apple Springs Orchards in nearby Clarksburg, the Ardiel family is also experimenting with ways to push density up and keep costs down. Kyle Ardiel showed off a small block of V-trellis Honeycrisp that he planted this spring, including a few rows of Royal Red Honeycrisp on G.41 that were planted as small potted trees, a cheaper alternative to traditional dormant nursery trees.

“It was not a fun planting. I basically crawled alongside the planter” to place the potted trees that were 2 to 12 inches tall, he said. Months later, they were growing well despite weed competition; they can’t spray until the trees get a little taller.

Overall, the block cost $50,000 an acre to plant, including the trees, which were planted at 11 feet by 1 foot at a trellis that angled out 10 degrees. “If I can get 50 apples per tree when they are full grown, that’s 80 to 100 bins per acre,” he said.

Keeping upfront investment costs low was not a priority at the next orchard the tour visited. Pulling in to Sandy Creek Orchard, the tour attendees felt themselves transported from Ontario to South Tyrol, Italy. But actually, it was the system that was transported, complete with concrete posts, black hail netting and every cable, clip, and clamp required to install them.

“You are absolutely right if you are thinking it’s not cheap to float cement posts over on a boat,” said Ian Furlong, the Ontario farmer managing the new Sandy Creek Orchard for Italian investors. But the owners wanted to grow in the system they know and brought Italian contractor FruitTop over to install “a one-stop solution.”

The owners also brought in an Italian horticulturist with experience growing in this system, said Furlong, himself a cash crop grower making his first foray into orchard management.

The first 15 acres of Honeycrisp on Malling 9 were planted last year, with another 20 acres this year, all at 10 feet by 26 inches. They plan to plant 350 acres or so over the next 10 years, he said, but there’s been a big learning curve the first two years.

“I am glad we only got 15 acres planted last year and now 35 this year because I want to see where this management approach will take this apple crop into the future,” Furlong said. “We have to see where that economic threshold is going to be.”

That’s probably the question on every Ontario grower’s mind when it comes to any and all of the new systems. And only time will tell. Good thing he invited everybody back in five years to see how the ambitious plans are paying off. •

—by Kate Prengaman

Related:

—Spray specialist promotes crop-adapted approach

—The right tools for the job (includes video)

Leave A Comment