—story by Kate Prengaman

—photo by Ross Courtney

—graphic by Jared Johnson

The standard advice for surviving the apple industry’s present downturn is to use block-level accounting to understand which orchards are paying their bills and which are bleeding.

Now, new cost-of-production budgets developed by Washington State University economists can help individual growers answer that question.

The budgets also provide tools for the industry to better communicate the economic crunch it faces.

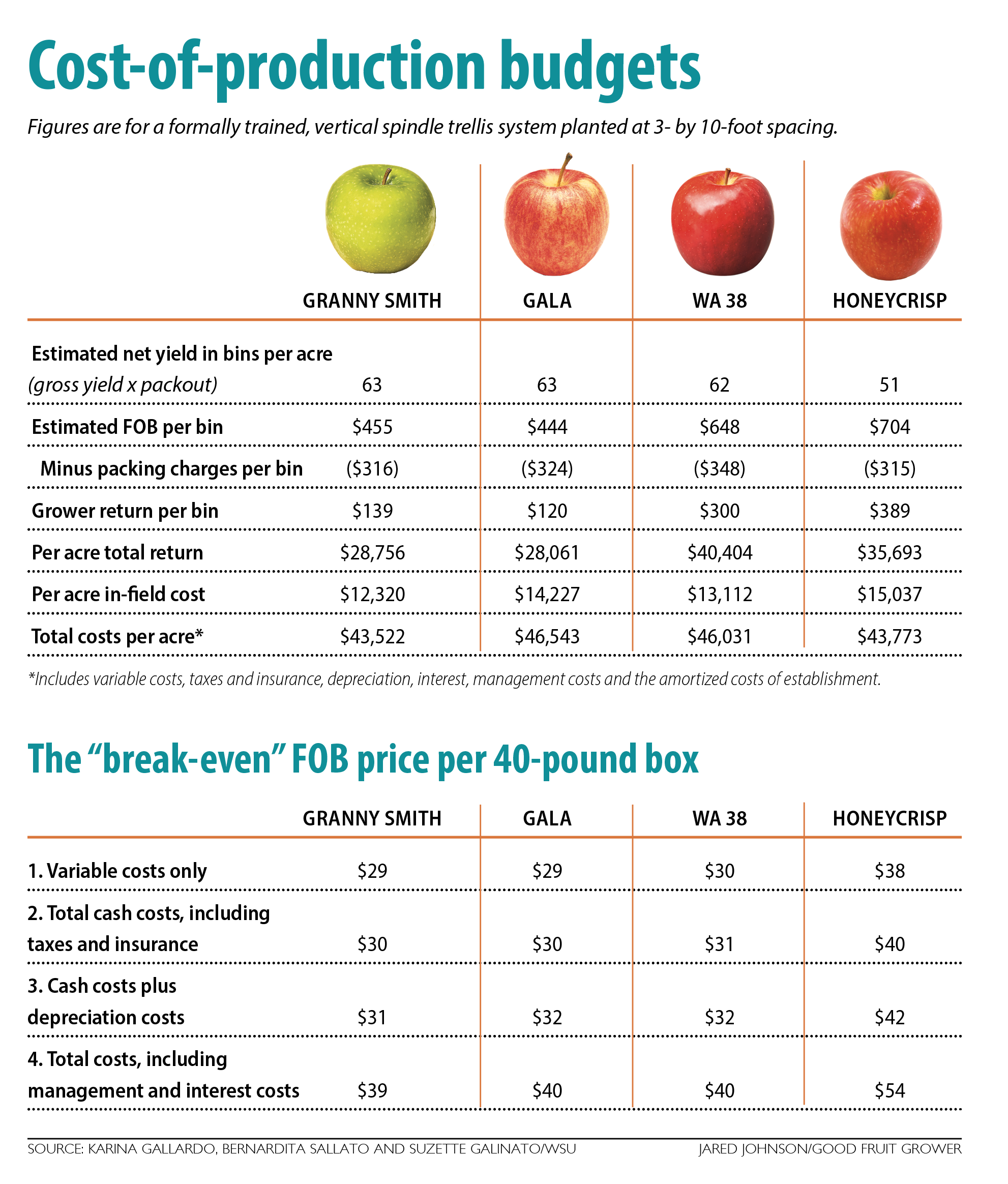

Extension economists Karina Gallardo and Suzette Galinato have produced cost-of-production budgets for tree fruit growers for over a decade, and with every new report, they refine their approach, Galinato said. For the 2024 Honeycrisp, Gala, Granny Smith and WA 38 budgets, they collaborated with tree fruit extension specialist Bernardita Sallato to get the most realistic scenarios for growers squeezed between rising input costs and flat or falling prices.

“We wanted to have the range (of practices) that we as a WSU team would recommend,” Sallato said. For example, the nutrient budget hasn’t risen as much with inflation as one might expect, because growers have become more efficient with their nitrogen applications. She went back and forth with many growers to fine-tune all the costs that go into the budgets.

“We feel good in the sense that the numbers are realistic, but at the same time, we feel afraid for the industry,” she said.

That’s because the conclusions show what growers have been saying for the past year: Returns are not sufficiently covering their costs of production, especially for commodity varieties such as Gala. Inputs include a 2024 hourly labor cost of $23.75 per hour, calculated using the Washington AEWR of $19.25 plus an H-2A fixed cost of $4.50 per hour. The gross returns are based on industry data from 2020 to 2023, but not the 2023–24 crop year.

Editor’s note: This story was updated to correct the FOB total cash cost, including taxes and insurance, for Gala in the preceding chart.

WSU’s analysis tool is also valuable for industry groups, such as the Washington State Tree Fruit Association, to use when talking with policymakers about the pressure growers face, said Jon DeVaney, president of the association.

“It’s a good indication of the limited ability growers have to cut costs and the challenge of absorbing new ones,” such as the increasing H-2A wages, he said.

Policy people often ask if he can provide the “break-even price” for growers, DeVaney said, and it’s a difficult question to answer — not least because growers’ budgets and farming choices vary. Moreover, there are multiple ways to define “break even,” depending on an individual grower’s timeline.

So, in the new budgets, the economists presented four different lenses through which to consider the idea of a “break-even return” for each variety in full production:

—Total variable costs.

—Total cash costs, which includes variable costs plus land and property taxes, and insurance costs. This allows the grower to stay in business in the short run.

—Total cash costs plus depreciation costs. This allows the grower to stay in business in the long run.

—Total costs, which includes management costs set at $750 an acre and interest costs, including the 5 percent opportunity cost growers could have gained with a different investment of their capital.

“The variable cost is the minimum survival cost. If we aren’t making that, we are losing cash farming,” Gallardo said. “The fourth level is the luxurious one (that) covers opportunities costs, which is where you want to be in the long run, because you want to renew and plant new orchards.”

The good news: Narrowing break-even returns into these categories can help growers realistically assess which blocks can weather the present market downturn.

“In tree fruit, we have high fixed costs, which allows you to operate if your revenues fall in the middle,” between cash costs and economic costs, Gallardo said. “If you are not covering all your economic costs, you can still operate.”

But the bad news: Galas and Granny Smiths returning less than $28 per box fail to even cover the variable costs of growing them in 2024. Over the past five years, Gala has an average FOB price of $24 per 40-pound box, and Granny Smith $26, according to data from the Washington State Tree Fruit Association.

“According to our studies, a price lower than $30 is not sustainable,” Gallardo said.

The researchers don’t enjoy giving bad news, she added, but the value of the tool comes from its representation of real-life situations, as much as possible.

For Honeycrisp, the budget is based on $44 per box FOB, which manages to cover total cash and depreciation costs. Similarly, WA 38, the apple marketed as Cosmic Crisp, can cover its total cash and depreciation costs at an FOB of $35 a box, thanks to higher yields and packouts than Honeycrisp. Both, however, fall short of covering total costs, which include the management and interest costs.

The cost-of-production budgets are always valuable to the industry as it grapples with making changes, but the tiered approach to what constitutes “breaking even” is particularly valuable right now, said Jim Doornink, a Wapato, Washington, grower and longtime chair of the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission.

“The question is, ‘How close to not making money is it?’” he said. “You can use Karina’s budget and take out the return on investment, take out the renewal reserve, and you can do that for a few years, but if you do it for 10 years, you’ve got old varieties and now no reserve money for renewal.”

For growers, the budgets are a completely customizable tool once they download the spreadsheets. WSU published a video explainer earlier this year to help (watch the video at:

tiny.cc/WSU-budgets). Have a smaller farm across which to spread tractor maintenance costs? You can adjust that. Spend more on thinning or less on chemicals? You can rework the spreadsheets with your own numbers.

Sallato encouraged growers to use the tool to provide some perspective on how their own costs of production compare to the published estimates and to play with their own numbers.

“The biggest thing we hear is growers want to understand where they can reduce costs and not affect fruit quality,” she said.

For herself and other researchers, the budgets also spotlight the value of improving practices and adopting new strategies and technologies.

“For me, it’s looking at what areas we — as researchers — can make an impact to the industry,” Sallato said. For example, her own work around more efficient nutrient management offers marginal savings compared to the labor cost increases growers face. But when better nutrition can increase quality and packouts, it quickly has a big difference on the other side of the equation. “It helps us put things in perspective.” •

Leave A Comment