Michigan spent decades as the top blueberry-producing state, growing more than half of the U.S. crop in 1993. But in the ensuing years, rapid growth in other states and other countries — the so-called “blue wave” — overtook the Great Lakes state. Washington and Oregon volumes now far outweigh those in Michigan, and Georgia and California are heading in the same direction.

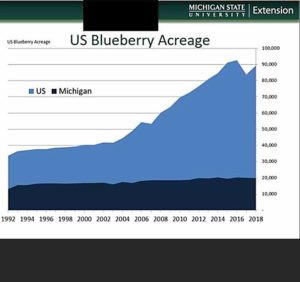

By 2018, Michigan was down to producing 12 percent of the national crop, according to Mark Longstroth, a retired Michigan State University small fruit educator. Before retiring earlier this year, Longstroth summed up Michigan’s situation during the Great Lakes Fruit, Vegetable, and Farm Market EXPO last December. Though Michigan blueberry acreage grew from 15,000 in 1992 to 21,700 in 2018, overall U.S. acreage grew from 33,000 to more than 89,000 in the same period. And the majority of Michigan’s acreage is more than 30 years old, not nearly as efficient as the new plantings in other states. Michigan produces an average of 4,100 pounds of blueberries per acre, compared to 11,700 pounds per acre in Oregon, he said.

Such numbers paint a picture of a Michigan blueberry industry that’s falling behind, but according to Good Fruit Grower interviews, Michigan’s multigenerational blueberry farms have been preparing for the blue wave for some time.

“Most growers who’ve been around for a long time have been talking about the blue wave just as long,” said Shelly Hartmann, owner of True Blue Farms, a large Michigan blueberry producer, and chair of the U.S. Highbush Blueberry Council.

While Michigan hasn’t been the top blueberry producer since 2015, the state has been hugely influential to the U.S. industry’s development over time, and its experience and leadership will continue to be essential to the industry’s collective success. Also, Michigan still plays a critical role in ensuring the year-round availability of both fresh and processed berries, said USHBC president Kasey Cronquist.

Those interviewed described multiple adaptation strategies for Michigan growers. While some have cut back acres, especially processing acres, or stopped growing blueberries altogether, others are mechanically harvesting fresh berries, planting newer varieties, diversifying into U-pick sales, seeking new export markets or finding other means to survive.

Michigan’s food manufacturers buy local blueberries for value-added products such as cereal, snack bars, juices and alcoholic drinks — even pet food, Hartmann said.

Some farms have chosen to grow bigger, taking advantage of economies of scale, said Michigan Blueberry Commission executive director Kevin Robson. (Robson stepped down as director in July, after this interview.)

“The number one way we’ve found we can compete is sheer volume,” he said. “We need more pounds per acre to stay competitive.”

The number of Michigan farms with 200 acres or more grew between 2006 and 2018, while the overall number of blueberry farms in the state shrank from 575 to 505 in the same period, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Michigan producers continue to seek winter-hardy blueberries that consumers enjoy eating and that can hold their quality when shipped long distances, Hartmann said.

Brian Bocock, vice president of product management at Naturipe Farms, said growers are replacing traditional varieties like Duke, Bluecrop and Elliott with newer berries such as Draper, Aurora, Envoy, Keepsake, Last Call and Sensation.

For a long time, Elliott was the “only game in town” during the profitable late-season sales niche, a niche that has been filled by imported berries, grower Denny Vander Kooi said during a recent U.S. Highbush Blueberry Council podcast.

“A lot of our profit was made in the last four weeks of the year,” Vander Kooi told USHBC.

Rex Schultz, owner of Heritage Blueberries and fresh market sales manager for True Blue Farms, would love to plant newer, potentially more lucrative varieties than Bluecrop and Elliott on his farm, but it’s risky because new plantings take years to come to fruition, and you never know what the marketplace might want in a few years, he said.

Meanwhile, Michigan growers are refining and modernizing their growing practices. Where they used to “roll the dice” with rain, 80 percent of their production is now irrigated. They also plant more bushes per acre, utilize fertigation via trickle irrigation systems and take advantage of controlled-atmosphere storage to extend the fresh sales season, Robson said.

John Smith, whose family has farmed the same land in Southwest Michigan since 1959, has diversified to remain relevant as a small blueberry grower. He decided to transition his 35 acres to certified organic, a process he completed last year. Organic certification is not a common path for Michigan blueberry growers — he said the three-year certification process can be daunting — but Smith saw it as a way out of an increasingly dismal conventional market. He definitely earns higher prices for his organic fruit, but he’s still not getting the direct retail profits he wants.

“It’s quite depressing — the end price that a farmer gets for his product after the middleman and store,” Smith said. “It would be nice if we could get more money back in our pocket.”

To do that, he’s planning to open a U-pick operation next year. On-farm sales could double the price he gets at the grocery store. He’s also planning to grow and sell certified organic blueberry plants and expand his bedding plant sales, too.

Smith struggled to find enough hand labor to pick his bushes, so three years ago he bought an Oxbo 8040 harvester. He uses it to pick his fruit and the fruit of other growers.

In July, Smith was machine harvesting fresh-market berries on Schultz’s farm near Grand Junction. Schultz said labor shortages have driven growers to rely more on mechanical harvest of fresh berries. For a long time, concerns about fruit quality made growers wary of machine harvesting fresh-market berries, but today’s newer, more refined harvesters do a better job than the old machines that simply “beat the bushes,” Schultz said.

The adjustments underway will most likely lead to fewer acres of Michigan blueberries in the future, but they will also lead to higher yields per acre and better quality and flavor, Bocock said.

“The Michigan blueberry industry looks entirely different than it did 20 years ago, and will look entirely different in another 20 years,” Robson said.

—by Matt Milkovich

Leave A Comment