Robert Orpet, a tree fruit entomology graduate student at Washington State University, counts earwigs in a roll of corrugated cardboard in a Quincy, Washington, orchard last July. Orpet is studying whether the earwig, sometimes regarded as a pest in its own right, can serve as a biological control for woolly apple aphid. (Ross Courtney/Good Fruit Grower)

Turns out, earwigs aren’t so bad.

They sometimes eat plants, but don’t wreak destruction like the brown marmorated stink bug. They don’t bite people like mosquitoes.

And they certainly don’t crawl inside human ears to lay eggs in our brains the way medieval folklore and their name suggest.

They may just need a better press agent.

That’s where Robert Orpet comes in; at least, he hopes to when his research is complete.

For now, the Washington State University entomology graduate student has documented that where there are more earwigs, there are fewer woolly apple aphids. And woolly aphids are the true bad guys for apple growers.

A colony of woolly apple aphids sets up shop at the root of a Gala tree. The pests, identifiable by the fuzzy colonies they build, typically infest roots at points of new growth or where trees have been injured by cracks, winter damage or at the base of leaf axils. They have become a recurring concern for some growers. (Ross Courtney/Good Fruit Grower)

Woolly aphids can infest roots, cutting yields by up to 5 percent, and attack the base of leaf axils or any other damaged tissue, such as grafting points, winter injuries or pruning wounds. They also leave behind a sticky waste fluid that can harbor fungi such as sooty mold.

This year’s brisk winter conditions notwithstanding, aphids are becoming a recurring problem, said Tim Welsh, general manager of new varieties and orchard development for Columbia Fruit Packers in Wenatchee.

“They thrive on certain roots and varieties and have the potential to affect fruit quality and fruit renewal,” he said. “The population has not had severe weather … to knock them down over the past five years, and our chemical use has been very soft and a nonfactor in controlling WAA,” or woolly apple aphid.

Earwigs to the rescue

Research assistant Sam Martin collects an earwig trap, a rolled-up strip of corrugated cardboard affixed to a branch with a rubber band. The orchard near Quincy, Washington, has had recurring problems with woolly apple aphid, so WSU graduate student Robert Orpet introduced earwigs to several trial blocks to measure the response. (Ross Courtney/Good Fruit Grower)

Orpet believes earwigs might offer some relief.

In his field trials in a Winchester Gala orchard — owned by Columbia Orchard Management, the farming arm of Columbia Fruit Packers — woolly aphid populations were an average of 2.4 times higher in his earwig-free control blocks than in the trees with earwigs.

In the most extreme count on Sept. 20, the figure was six times as high.

To determine this, he actually went around putting earwigs in orchard blocks throughout the season, using some of the most inexpensive tools possible — a plastic bucket, rubber bands and rolled up strips of corrugated cardboard in which earwigs like to hide.

Robert Orpet, left, places new earwig traps throughout a Gala trial block while Sam Martin sprinkles new earwigs with a red bucket. (Ross Courtney/Good Fruit Grower)

In all, Orpet released 1,700 earwigs in each of five 39-tree blocks at a rate of 44 earwigs per tree; five other sections served as a control with almost no earwigs all season.

At the peak of infestation, he counted 1.5 woolly aphid colonies per tree in the control section but less than 0.25 colonies per tree in the earwig populated sections. Late in the season, after mid-September, earwigs disappeared, most likely retreating to nests in the soil for winter, and woolly aphid colonies went up.

So, though he still has more research to do, he knows it works.

Orpet’s research is part of a larger, three-year woolly aphid control project, funded by a Specialty Crop Block Grant through the Washington Department of Agriculture for $194,000 and the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission for $113,000.

Other studies

Other projects in other parts of the world — Belgium, the Netherlands and Australia to name a few — have come to the same conclusions, and earwigs also control other pests, such as codling moth.

In a study last year of DNA in earwig guts, entomologist Thomas Unruh found codling moth remains in 15 percent of the guts of dissected earwigs, the highest percentage of any other predatory insect or spider in the study.

The study was published in the journal Biological Control. Meanwhile, earwigs only caused 11 percent fruit damage to apples when they were isolated in a bucket with only apples to eat, not at all what they would face in an orchard.

“I strongly feel that earwigs are beneficial in apple and pear orchards,” said Unruh, now retired from his post at the U.S. Department of Agriculture laboratory in Wapato, Washington. “They may be seen eating an overripe or damaged fruit … but most of their time is likely spent feeding on insects both dead and alive.”

Orpet is doing similar DNA analysis as part of his project, looking for woolly aphid remains, or “signals,” in the guts of earwigs.

Earwigs also seem to work in pears.

Richard Hilton, extension entomologist with Oregon State University in Central Point, found that earwigs decreased the population of pear psylla.

Similar studies in Europe have reached the same conclusion. Hilton also has examined sampling methods for tracking earwig populations and development, work that has been folded into a phenology model by a Belgian researcher, and studied the effects of different pesticides on earwig survival.

“Furthermore, my work in pears with earwigs supports the categorization of earwigs as a very minor pest with superficial fruit damage occurring only in rare instances and at low levels,” he said.

If earwigs eat fruit, they prefer soft flesh, such as peaches.

In fact, earwigs go full-on Jekyll and Hyde when it comes to peaches, according to Diane Alston, an entomologist at Utah State University. In some of her department’s studies, earwigs served as a beneficial predator of green peach aphids early in the season, but caused up to 20 percent damage depending on population size when peaches ripened in August.

“Yes, their dual role as a predator in early to mid-summer, and as a frugivore in late summer is very interesting,” Alston said. “Management to synchronize earwig populations with pests such as aphids where they can provide biological control and then discourage high numbers when fruits are susceptible is key to making them bring value to the fruit grower.”

One of her graduate students is developing a degree-day model for earwigs in peaches to help growers time their management.

Earwigs’ effect on cherries is less clear, though the insects typically appear in orchards later in the season after cherries have been harvested, Alston said.

Public perception

Still, Orpet admits he will have a sales challenge when it comes time to convince growers to give earwigs a chance. Most people think of earwigs as a creepy-crawly pest, if they think of earwigs at all. The bugs don’t help themselves by being so mysterious, hiding all day and coming out to feed at night.

To help overcome the bad rap, Orpet is surveying and interviewing a variety of members of the industry including field representatives, growers, workers and researchers about their feelings and experiences with the insects. Some people may have heard about their benefits, others may not.

He wants to know “what kind of information would be most important to get out to them,” he said.

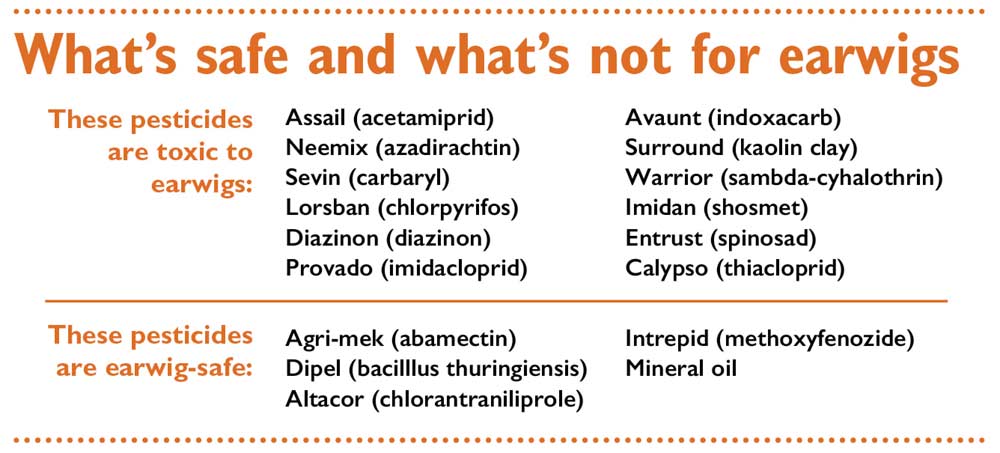

He’s also armed with several fun facts about earwigs to prove they are “charismatic.” For instance, they are one of the few insects that care for their young. In the meantime, he advises growers to avoid chemicals toxic to earwigs as much as possible and to avoid disturbing the soil. Earwigs overwinter in underground nests.

Pest control has no silver bullet, of course, and Orpet’s earwigs are no exception. For one thing, Orpet’s results involved population counts in the branches or high on the trunks of the trees.

Near the ground at the roots, however, his results showed no difference between the earwig populated trees and the control trees, suggesting the earwigs were not feeding on woolly aphids near the roots or that the aphids simply repopulated quicker than Orpet could count them.

Other studies have shown that galls on roots near feeding locations is one of the most important form of damage caused by woolly apple aphids, but it’s hard to study anything in tree roots without disturbing the tree.

“In conclusion, earwigs and other well-known natural enemies could possibly clean up above-ground colonies and that is a good thing even though what is going on underground is more of a mystery,” he said.

Still, Welsh of Columbia Fruit is anxious for Orpet’s results. He has introduced other predators to his Winchester orchard, where woolly aphids have thrived for multiple years.

“It’s my belief (earwigs) only attack apples that are already damaged so they should be a nonissue as it regards being a ‘pest’,” he said. “If so, it will be a great benefit to understand how to manage a population against WAA and perhaps other pests.” •

– by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment