The ideal sweet cherry crunches just slightly when you bite into it, the perfect combination of firmness and juiciness.

Quantifying that eating experience turns out to be tricky.

“Compression is not great. We find differences between how firm the fruit is and how crunchy an eater might find the fruit to be,” said Carolina Torres, the endowed chair for postharvest physiology at Washington State University.

She and her team spent the past two seasons looking for a better metric to track the attractive texture of cherries through hyperspectral imaging. That work is ongoing, but it overlaps with Torres’ other cherry research into the best strategies for storing fruit for up to 30 days and how improved quality metrics could guide storage decisions.

To both ends, the postharvest lab in Wenatchee painstakingly sampled some 10,000 cherries last summer, comparing traditional metrics such as compression or penetrometer tests to hyperspectral imaging and texture rating of experienced eaters.

It’s the first foray into cherry research for Torres since she joined WSU in 2019. In her native Chile, exporters commonly store fruit up to 45 days, and while the Washington industry enjoys a very different market, there’s industry interest in understanding storability, she said.

The texture conundrum

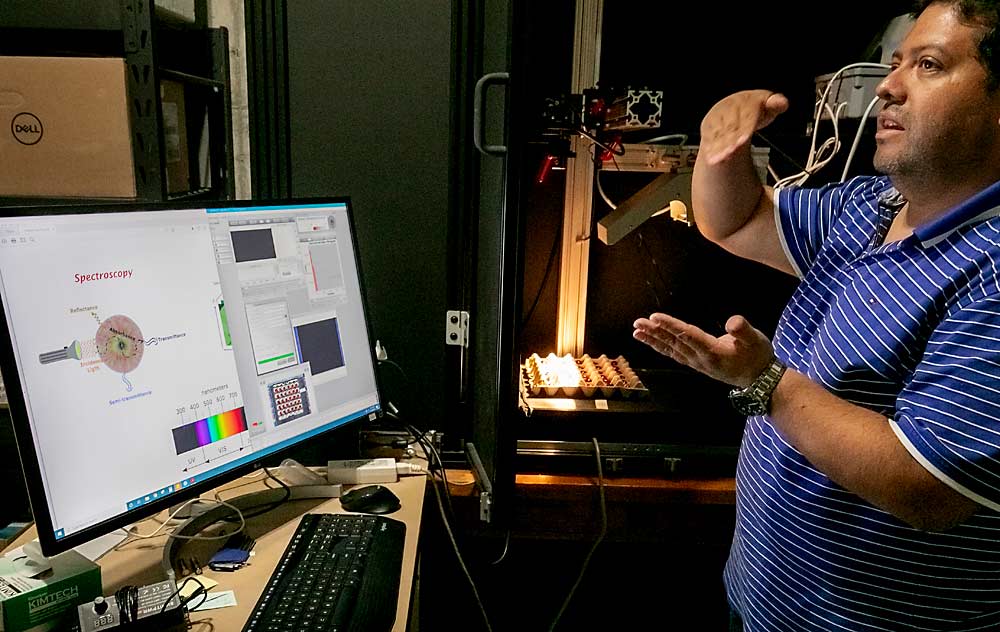

Rene Mogollon, a postdoctoral researcher in Torres’ lab who did his doctorate work in Chile using spectrometry to detect apple defects, leads the work on using hyperspectral imaging to assess cherry quality. The industry already uses optical sorting technology to assess size, color, defects and even Brix.

Before a model can be developed to translate the way light bounces off a cherry to understand its firmness, Mogollon needs to know which wavelengths to look at. A hyperspectral sensor collects data on wavelengths across the light spectrum, and only a few are relevant to the question of cherry firmness.

“The sorting lines have specific sensors for the ranges they need. It’s cheaper and faster than collecting the whole spectrum of the fruit,” like he is, Mogollon said.

For each cherry he scans, Mogollon also takes compression data with a FirmTech 2 and measures peel maximum force and flesh force with a Mohr Digi-Test penetrometer.

He’s still crunching data but, so far, differences between firm and soft cherries can be detected in two zones of the light spectrum, one of which has been associated with water balance in other fruit crops. His first model shows that those key wavelengths can predict the traditional metrics within 10 percent error. More data should decrease that error rate, he added.

The study includes Rainier, Bing, Skeena and Sweetheart.

“Each cultivar and each season has its own distribution on compression,” he said. “We need more time with cherries to standardize the values.”

This season, Mogollon hopes to refine the model to better align with traditional texture metrics and see how it correlates to the texture experience of eaters.

In addition, Torres partnered with WSU cherry breeder Per McCord to add some more uniquely textured cherries to the sample set. For example, one selection of interest — for her research — feels firm outside and soft inside, while another selection is crunchy to the core.

“We have followed those weird textures for three years to better explain the texture you experience when you bite into a cherry,” she said.

With the breeding program selections, Torres also observed the influence that harvest timing has on firmness and other quality metrics. McCord harvests multiple times for each selection, to figure out the optimal timing.

Storage strategies

The question of optimal timing comes up in the storage aspect of the study as well, Torres said. In her opinion, Washington growers generally harvest a little too late for storing fruit — because they rarely store fruit.

“I usually harvest (for research) at commercial harvest times, but to be able to store good-quality fruit, they have to harvest a little earlier,” she said.

To demonstrate the relationship between harvest timing and storability, her 2023 trial included two harvest dates, the commercial one and three to five days earlier. That wasn’t enough to see significant maturity differences, so this year she’ll harvest at 10 days ahead of commercial harvest.

The harvested fruit was divided into storage regimes including modified atmosphere packaging (MAP bags), controlled atmosphere storage at two different oxygen and carbon dioxide levels, and refrigerated storage. Some cherries were evaluated after 15 days and some after 30.

The outcomes?

“It’s very variety-dependent. And season dependent,” Torres said. “I would want to see more consistency, but we don’t. All of them are better than the control cherries that are just cold.”

The MAP bags are commonplace in Chile, she said, lowering oxygen to 10 percent and increasing carbon dioxide to more than 5 percent in 10 days. (For context, regular air is 21 percent oxygen.) They also help prevent dehydration and stem deterioration.

“If you are trying to get out of bags, for sustainability, you can use CA and keep the humidity levels high, even, but you will have different outcomes in different seasons,” she said. “Unfortunately, there is no winner yet.”

Cultivars for keeping?

Which common Pacific Northwest cherry cultivars have the most potential for successful storage?

Rachel Leisso, the new postharvest physiologist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture based in Hood River, Oregon, aims to find out by evaluating seven cultivars after four weeks of storage at either 31 degrees or 40 degrees Fahrenheit, with and without modified atmosphere bags.

The project began last season, funded by the Oregon Sweet Cherry Commission and Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission. Leisso looked at Coral Champagne, Black Pearl, Chelan, Santina, Bing, Skeena and Regina.

While the data is preliminary, it’s clear that the modified atmosphere bags helped the fruit retain quality longer under both temperature scenarios, Leisso said when she presented an update on her work to the commissions in November. As for varietal differences in key quality metrics, such as the absence of shriveling, pebbling or cracking and retention of good firmness, acidity and stem quality, another season’s data is needed, she said.

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment