Trade difficulties aside, China has long been high on sweet cherries, importing them at prices that almost redefine premium. That goes for U.S. cherries and those from Chile.

But the Middle Kingdom grows its own cherries, too, investing heavily in modern techniques, new varieties and the latest rootstocks to raise fruit of higher quality and larger quantity. And they’re doing quite well, said Matt Whiting, a horticulturist at Washington State University who specializes in cherry tree physiology.

“I would be more concerned about local production displacing our cherries than a trade war,” said Whiting, who spent September 2019 as a visiting professor at Shanghai Jiao Tong University. In 2017, China was the largest export market for Northwest cherries, at 3 million boxes. Last year, the volume dropped to about 1.7 million boxes after two years of trade conflicts between China and the Trump administration.

Graphic: Ross Courtney and Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower)

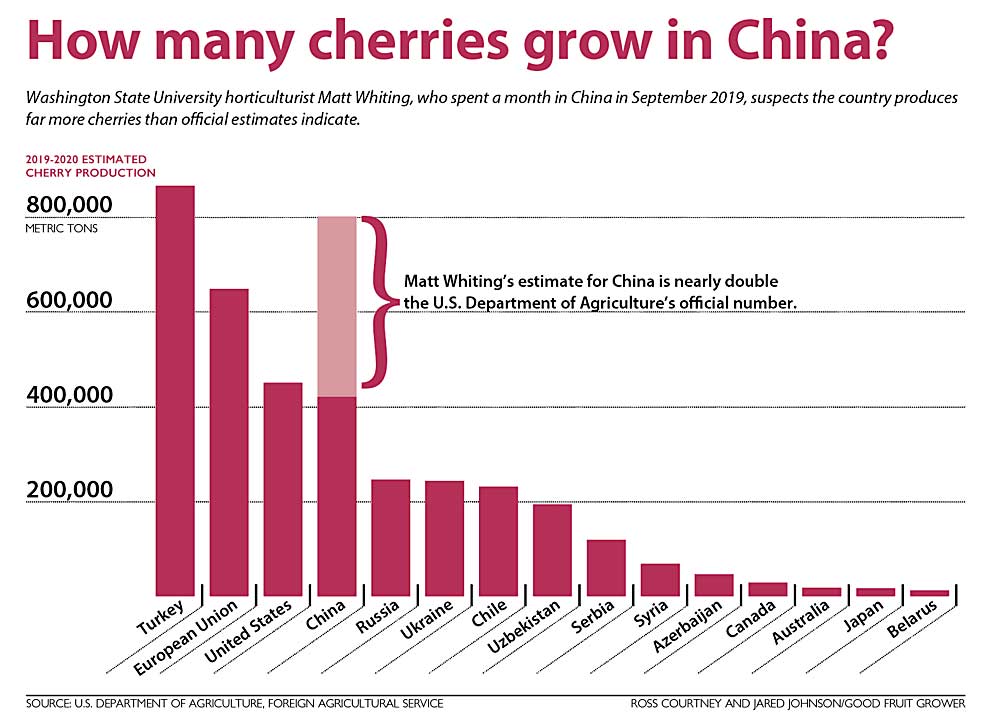

Whiting suspects China produces way more cherries than most estimates acknowledge. Statistics from official sources vary wildly, but the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Foreign Agricultural Service estimated about 420,000 metric tons of cherries in 2019 — that’s equivalent to 37.5 million 20-pound boxes. That number includes both sweet and tart cherries, but market experts believe most of them are sweet.

Whiting said he thinks it’s more like 800,000 metric tons, and that’s probably a conservative estimate. He bases that on acreage and yield estimates he heard from numerous researchers, production managers, growers and local government officials in China. That would make China the second largest producer, behind Turkey and ahead of the United States.

Regardless of the real number, China’s cherry production is getting more sophisticated and larger scale.

Modernization

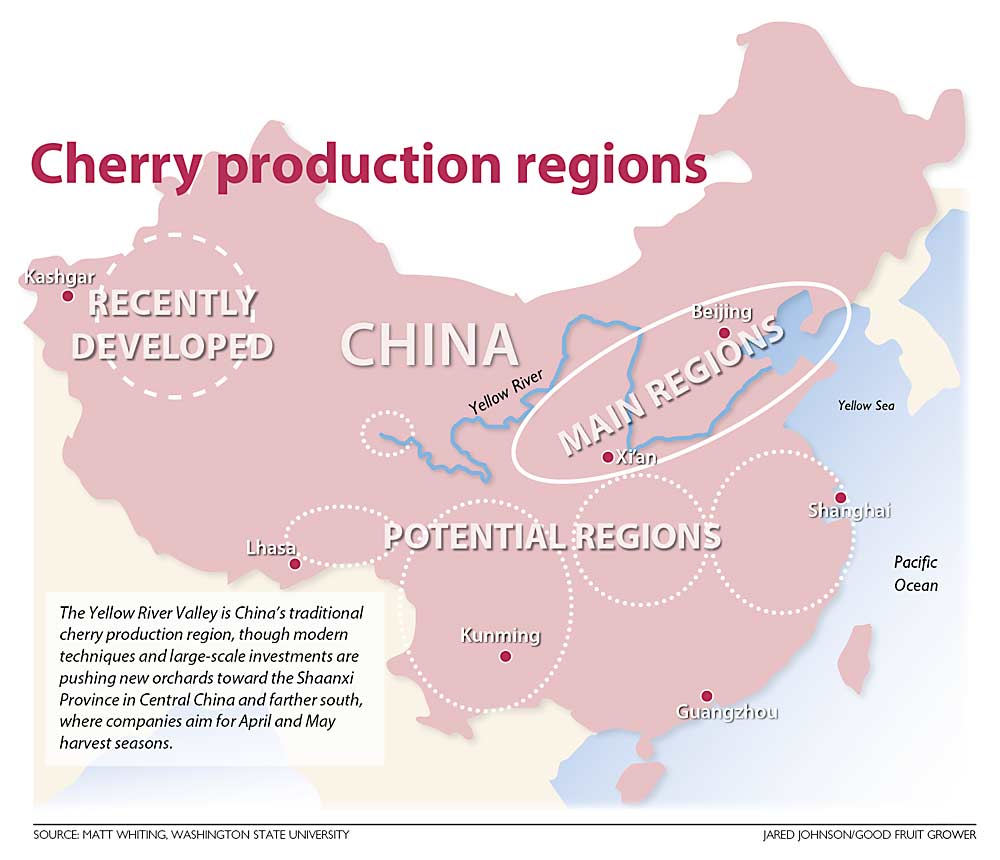

For the most part, China’s agriculture landscape consists of small acreage plots with low yields supplying processing, packaging and distribution networks that are both decentralized and unreliable. Cherries typically grow in the northern provinces along the Yellow River.

All that is changing, rapidly.

In Whiting’s travels, he witnessed vast new cherry orchards with modern training systems, uniformly managed across thousands of acres. Production managers are using growth regulators, scoring, summer pruning, trellises, the works.

“Quite simply, they’re getting better,” he said. “They will definitely compete with Northwest cherries.”

At the Cherry Institute in January in Yakima, Washington, Whiting showed growers pictures of a 300-acre Regina orchard planted four years ago near Xi’an, a city in the Shaanxi Province of Central China, by Haisheng Co., the world’s largest apple juice producer. It’s trellised with a clean fruiting wall and had been neatly pruned. “It’s managed as well as any block in Washington,” he said.

Further south, companies have cherries under various greenhouses and coverings to protect them from the rain and aim for a harvest timing in April and May, after Chilean imports have left the market and before California’s have arrived.

Graphic: Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower)

Yes, they struggle with low chill and doubling, Whiting said, but the country has nearly a dozen active breeding programs looking for scions and rootstocks that will tolerate the southern areas. Better adaption to humidity and summer rains will help growers serve massive, dense population centers such as Shanghai, where consumers crave cherries. Netted U-pick farms fetch $12 per pound in the area.

Typically, yields are between 2 and 3 tons per acre, a far cry from Washington yields that sometimes reach double digits, but even low yields would pay off at those prices, Whiting said.

“If you could produce, let’s just say 1 ton, the potential returns are so extraordinary, it makes sense,” he said.

China also grows a lot of Tieton cherries, a variety bred at Washington State University.

A marketing perspective

Keith Hu, international marketing director for the Northwest Cherry Growers, based in Yakima, also has seen larger orchards and modern techniques in his travels in China. At times, U.S. cherries have had to compete for retail shelf space in northeastern Chinese cities.

But overall, he still puts China’s horticulture techniques, packing efficiency, cold chain and distribution networks about 10 years behind the U.S. Also, the growth in southern China, with April and May harvest times, will compete more directly with California cherries than those of the Pacific Northwest, which hit their peak in late June.

Land ownership policies are the biggest hurdle for China’s production companies seeking the economies of scale. Most agricultural property still is owned by the state and farmed by small-acreage growers, limiting how much producers can implement modern techniques.

“Unless they change the land ownership, otherwise I don’t think they can compete with us,” Hu said.

Property ownership poses a hurdle, but not a brick wall, said Whiting, who asked around about that in his visit. Government officials are willing to partner with private companies to make larger investments happen in return for promising to hire the displaced workers.

“The government is willing to make these deals,” Whiting said. •

—by Ross Courtney

Related:

—China ramps up cherries

—Cherry marketers testing foreign waters

—Rainiers break a record in the 2018 cherry season review

—All aboard the cherry express

yeah.. go ahead and cut your own throat,, keep giving them all the research and varieties they ask for

Thanks for the comment. You bring up a good point. We reached out to the researcher, Matt Whiting, and this is what he said in response:

“I wasn’t there to help Chinese cherry growers. Most of my time/effort was spent on campus in Shanghai, teaching, and advising graduate students on their research projects. We also were looking for opportunities to collaborate on research issues that are common to China and US cherry production. ‘They’ didn’t ask for research, nor varieties, to be clear. ‘They’ have their own research teams across the nation (far more researchers involved in sweet cherry than here in the US) and breeding programs (which you mention in the article) to develop locally-adapted genotypes.”

The northeastern province of Liaoning where I live is coveted for their sweet abundant cherries and it’s big business as well. My brother-in-law just dropped off about 5 kilos of both red and yellow cherries that he picked this morning. In response to the “throat cutting” comment above I’d just like to say that China hasn’t stolen anyone’s markets or job’s. If American producers have lost market share or jobs to China in any industry it is because American companies have moved their operations to China in search of cheap labor. Corporate greed is the problem not China.