Change is hard and expensive.

But not changing could cost pear growers even more.

That’s what worries Shawn Cox, a Cashmere, Washington-area pear grower and the new general manager of the Peshastin Hi-Up Growers cooperative.

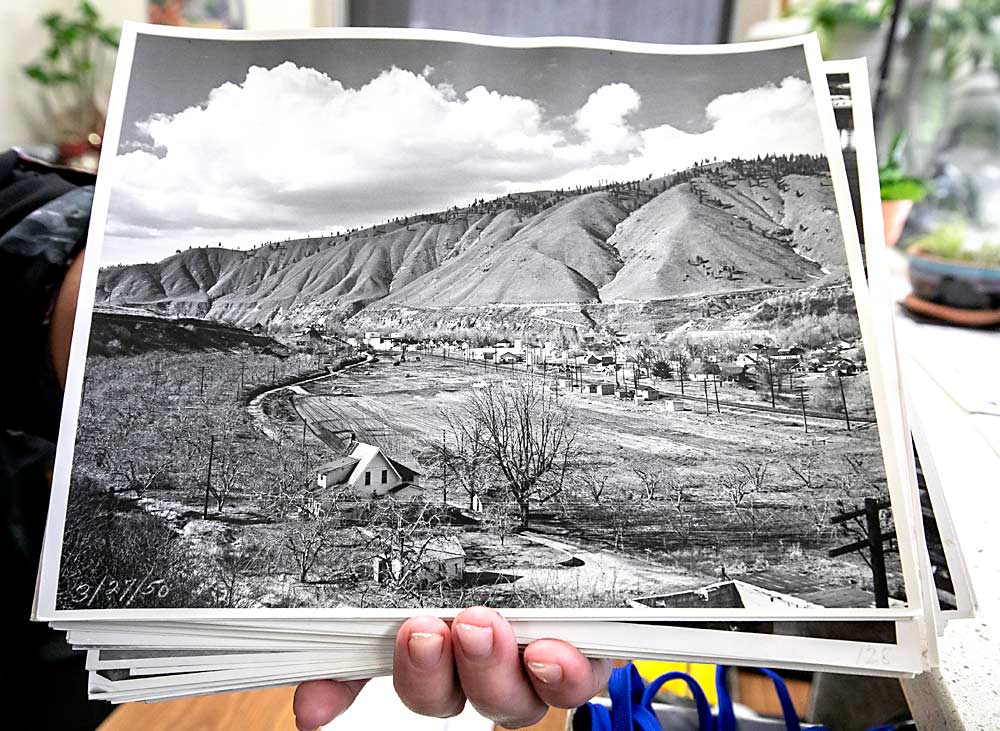

“The reason this community is the way it is — is pear farming. But it’s becoming more and more difficult for pear farmers to make money,” he said.

For decades, growers picking steady yields of 45 or 50 bins an acre saw little reason to renew orchards into the same varieties and rootstocks they already had, until increasing costs of labor and inputs, coupled with yield declines in aging blocks, put the squeeze on small family farms — all while pear prices failed to keep pace. Grower-owned cooperatives have a responsibility to help members navigate these challenges, Cox said.

“As I told growers at my first meeting, my job here at the warehouse is going to be to figure out how to put more money back into the ground so you can pay for your expenses, so you can pay yourself … and to make a little bit more on top of that and convince you to replant and reinvest in your orchard structures,” Cox said. “In the short term, there are many things we can do at the warehouse to improve grower returns.”

Cox’s call for change marks just one aspect of the leadership shakeup at all three pear cooperatives in Washington’s Wenatchee River Valley. From doubling down on what co-ops can do best, such as investing in new growers or sharing the burden of food safety regulations, to building a new labor solution for the valley, new managers are thinking big about what co-ops can do to keep their industry sustainable.

New leaders “tend to shine the light in spots that haven’t been shined,” said Ray Schmitten, a fourth-generation grower who took the helm at Blue Bird Inc. this spring, after years in grower-services roles with Blue Star Growers.

He brings a new perspective with his background in horticulture, fruit quality and grower relations, while Cox is a process engineer by training and Gene Woodin, the new Blue Star Growers general manager, previously served as general manager at Congdon Orchards in Yakima. At each warehouse, they hope to find more operational efficiencies and maximize fruit quality to continue to grow grower returns.

“I want to drive home that we are doing this for the family farms,” Schmitten said.

With less than a year under their collective belts, Schmitten, Cox and Woodin hit the ground running by forming a collective effort between their three boards of directors to explore building an H-2A program for the valley. They credit that nascent collaboration between competitors to the relationships in the valley’s pear community and the existing co-op ethos.

“What’s on the foremost of everyone’s mind is: ‘What can we do to get into the 21st century and bring more returns back to the land?’” Woodin said. He grew up in a family of Yakima Valley orchardists but spent years in Cashmere working for processor Crunch Pak. “The co-op model, for me coming in as an outsider, seems very advantageous to growers in an era with competition from large, vertically integrated farms that can make it difficult for small growers to play.”

Grower services

Taking the manager role at Blue Star delivered a master class in what co-ops can do to help small family farms access the economies of scale that larger farms enjoy, Woodin said. The co-op has 70 growers farming some 2,600 acres of pears.

At Blue Star, that model of grower support encompasses operating loans (see “Old trees, new growers”), a food safety program and a mechanic shop that keeps members’ equipment up and running. Woodin wants to lean into those advantages to attract new growers to the industry in the future.

Small growers can struggle to keep up with constant regulatory change, so the co-op-wide food safety program is a huge asset, said board member Erica Bland-McConnell. Warehouse staff keep everyone current on rule changes, and audits rotate to different farms each year, lessening the burden.

Her family has brought their pears to Blue Star for generations because they trust the grower-owned model, even in tough times.

“That’s what I love about our board — we’re not just chasing pennies, we’re making decisions for the good of everyone,” she said.

Blue Star mechanics have repaired growers’ equipment for years, but five years ago the co-op invested in a new shop designed to care for everything from the warehouse’s Class 8 trucks to growers’ tractors. The new shop has plenty of space for the team of five mechanics, an enormous parts inventory, a wash bay to clean equipment of all sizes, and an oil/water separation system to ensure nothing washed off that farm equipment ends up in the river, said shop manager Ron Sears.

In the off-season, he schedules out members’ maintenance, but during the growing season, Sears likens prioritizing repair needs to hospital triage.

“We know that if they don’t get that spray on when they need to, it’s their livelihood,” he said. He will make in-orchard repairs if he can or offer loaner equipment if he can’t.

The discounted labor rate for grower-members is also a benefit, but it is strongly in the warehouse’s interest to have growers applying timely sprays or getting bins loaded and hauled as soon as possible, Woodin said.

“Fruit sitting in a field overnight because the truck broke? That’s the difference between storing it until January and storing it until June,” he said.

Labor

Today, labor cost and availability top the list of growers’ challenges, but the H-2A program is inaccessible to many small growers.

Instead of each co-op pursuing its own program, the leaders decided to combine forces to see if they could grow a program faster, Schmitten said.

“We look at it as pears against the world at this point,” Schmitten said.

Ironically, many of the effort’s leaders, who have been meeting over the past six months, already have their own H-2A programs, Schmitten said.

“We are willing to share our housing and our contracts so we can build up a program,” he said. “We’re walking before we run.”

Several small groups of growers have experience sharing contracts, he said, and they want to build on that and grow participation and proof of concept before investing in additional housing.

Of course, the devil is in the details regarding how workers would be shared during the hectic harvest season. Bland-McConnell, on the Blue Star board, remains skeptical about the logistics and the cost.

“In reality, H-2A is another cost, and it’s hard to put money into that without a guarantee” that your farm will have workers when it needs them, she said.

Woodin agreed but said he sees a warehouse-level labor program as both a way to secure growers the labor they need and a harvest execution tool to help the warehouse manage quality.

“That’s the goal from the top, from the warehouses. We can’t improve fruit quality if we can’t get it picked at the optimum window,” Schmitten said.

Orchard renovation

Similarly, warehouses have a vested interest in orchard renewal for improving fruit quality and efficiency.

“The co-op has a responsibility to help bring information to growers when it comes to technology, planting innovations and varieties,” Schmitten said. “And we can’t be afraid to collaborate.”

But what that cost-effective, efficient renewal looks like remains an open question, with lots of experimentation underway. For an example, Cox took Good Fruit Grower to a high-density-for-the-time Bartlett block his grandfather planted in the 1990s, with 15-foot row spacing and 7.5 feet between trees.

“It worked really, really good for about 15 to 20 years. At its peak we were picking 50 to 60 bins an acre year over year,” he said. Today, it’s still one of his most profitable blocks, but it’s becoming hard to manage.

“Labor is just going to get too expensive. We have to have higher-quality, higher-producing acreage we can automate,” Cox said.

So, to teach himself about growing higher-density pears, in 2020 he took a chainsaw to two rows of trees and trained up four new shoots into a V-trellis system. He likes the planar system but not the blind wood that developed in places.

“It takes so much more attention to detail. You can’t let things go where you don’t want them to go,” he said.

Since then, Cox has launched two other high-density experiments: a trellised Bartlett block trained similarly to a UFO cherry system — which was very expensive — and a just-grafted-over block he plans to train in a multileader style.

“I like experimenting and engineering and trying to figure things out,” he said. “I hope we can have more field days as a co-op, here and with other growers, to talk about what we’re learning.”

That sort of community conversation and mentorship with replanting reduces each grower’s risk, said Blaine Smith, a Cashmere-area grower and Hi-Up board member who recently invested $60,000 per acre in a new planting.

Planted at 12 feet by 2 feet in a steel trellis system, Smith trained the HW 624 trees (marketed as Happi Pear) with three leaders to control vigor and keep fruiting wood small. He uses a click pruning approach, like he does in his apples, to promote weak response growth. It’s a system that showcases what he’s learned from mentors and researchers and tours.

“You’ve heard the saying: ‘You grow pears for your heirs.’ We can’t do that now because we have to make money to stay in business,” he said. “I can’t take 10 years to learn about rootstocks or take 10 years to learn to prune my tree right. I have to go to mentors that have already done things to learn what the mistakes were instead of reinventing the wheel.”

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment