Noah Gizdich walks through the north part of the family ranch in Watsonville, California, where the family has planted Newtown Pippins between older trees. The older trees, with prop wood stored between the branches, were planted with a much larger spacing. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

One hundred years ago, Watsonville, California, was one of the apple leaders of the world, shipping fruit around the globe, supporting dozens of local packing sheds and giving rise to Martinelli’s, arguably the most famous sparkling apple cider producer in the United States.

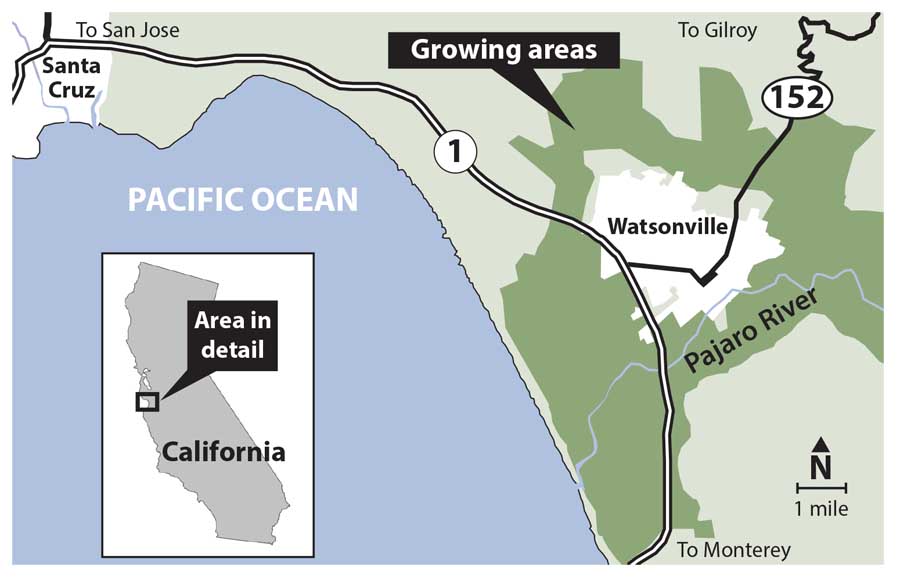

Nowadays, Martinelli’s is practically the only reason there are any apples at all in the temperate Pajaro Valley, wedged between Monterrey and Santa Cruz, while Watsonville is better known for strawberries.

Martinelli’s “is what keeps apples here in the valley without a doubt,” said Vince Gizdich, a third-generation Watsonville grower.

Martinelli’s buys about 95 percent of the apples grown in the Pajaro Valley. “If we suddenly disappeared, those growers would have nowhere to go with their fruit,” said Gun Ruder, vice president of Martinelli’s.

Decline of apples

Martinelli’s has two production centers in Watsonville, which is surrounded by apple and berry farms. This facility sits downtown. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

Swiss immigrant Stephen Martinelli founded the company in 1868 with his first cider press.

The historic building still operates downtown, though the bulk of the processing, warehousing and shipping now happens at a newer, larger facility toward the edge of Watsonville, population 52,000. Martinelli’s now has 450,000 square feet of processing space and 200 employees.

However, the Watsonville area lost apple favor as Washington’s production soared in the second half of the 20th century, while new varieties — namely the Granny Smith — surged past the Pajaro’s staple Newtown Pippin in popularity.

Meanwhile, farmers in the area began switching to the more profitable berries, which reach production sooner and often yield multiple crops in one year.

In 1909, the Pajaro Valley had 14,000 bearing acres in apples — roughly 1 million trees — and produced 2.5 million boxes for 40 packing houses, according to a history published in 1994 by the San Jose Mercury News.

In 2013, Santa Cruz County — home of Watsonville and the Pajaro — had just over 2,000 acres, third behind San Joaquin and Sonoma counties, according to the California Apple Commission. Most of the decline has happened in the past 30 years, Ruder said, mirroring the trend of California overall.

Preserving the region

Newtown Pippin apples await processing by the juicer in the background at the Gizdich Ranch. (Ross Courtney/Good Fruit Grower)

Martinelli’s executives still consider the Pippin the “backbone” apple for all their blends and insist the variety tastes best when grown at home.

So, they protect their backyard supply with deals only available to local growers.

Not including production incentives, Martinelli’s offers contracts to Santa Cruz County growers that range from $200 to $300 per ton, way above the spot market prices hovering around $100 for bulk apples from Washington.

“We wouldn’t have the diversity in apples (without Watsonville),” Ruder said. “We believe very strongly our flavor profile would be affected.”

Watsonville, California growing region. Source: Google maps. (Marcus Michelson/Good Fruit Grower)

The company also extends incentives for local growers to continue planting more Pippins and a companion cider variety, the Mutsu, by setting a floor for prices for the first 10 years of production for new blocks and simply giving growers replacement trees for free.

The manufacturer also extends long-term leases to retiring farmers and hires its own orchard managers to run them. The company owns no farm land.

A farmer’s adaptation

Growers like the Gizdiches and their neighbors specialize in the Newtown Pippin, an heirloom variety known for tart crisp flavor that holds up under cooking and months of storage.

However, it eventually lost out to the prettier Granny Smith due to its inconsistent shape, color and russeting.

Vince’s son Noah, 25, walked through his family’s 60-acre orchard in early March —white blooms dampened by recent rains and surrounding green hills obscured by fog tendrils.

He described the Gizdich Ranch’s ever changing patchwork of old and new. Some blocks are brand new with drip irrigation and high density planting, while others push 60 years old, spaced 30 feet apart. Bundles of old prop wood lean against a few of the trunks ready for the weight of fall.

“Nobody really plants them like that anymore,” Noah said with a laugh.

Old Newtown Pippins grow at Gizdich Ranch surrounded by berry farmers in the Pajaro Valley. The Valley, which rests about 20 miles southeast from Santa Cruz, is a coastal community that was once one the state’s top apple producing areas. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

Some Pajaro Valley growers produce apples exclusively for Martinelli’s, though a few — such as the Gizdich Ranch — have diversified and even fewer grow for the fresh market. “Most of the growers here now aren’t fresh market producers,” Vince said. “There’s just a couple of us left in town.”

The Gizdiches mix commercial cropping with U-pick, a pie and gift shop, a juice press and seasonal fresh market sales to San Jose and San Francisco grocers.

In the past few years, they also have been filling 250-gallon containers with juice for hard cider companies.

Also like other growers in the Pajaro Valley, they don’t have controlled atmosphere or refrigerated storage facilities, though they are one of the few who have their own packing lines. Few farms in the area are bigger than 100 acres.

Martinelli’s takes about 20 percent of their volume, much lower than most of their neighbors. But the company provides them stability for apples that wouldn’t sell anywhere else.

“They probably don’t have to give us what they do because they purchase from other places in high volumes,” Vince Gizdich said.

History of the farm

Noah, left, and Vince Gizdich and their Watsonville, California, neighbors hang on in the once thriving apple region with a pie shop, their own juice press, U-pick, Bay Area fresh markets and a reliance on cider giant Martinelli’s. (Ross Courtney/Good Fruit Grower)

Vince Gizdich I — Noah’s great-grandfather — started the farm in the 1920s after moving from Croatia, the ancestral homeland of many Pajaro Valley families.

Vince II set the family’s course of slowly converting to semi-dwarf varieties, including new Pippin, but also Winesap, Red Delicious, Honeycrisp and Mutsu, hitting the high-density trend earlier than many neighbors.

“My grandfather, he was a clever man,” Noah said.

They do it piece by piece, sometimes lopping off branches of the older trees to give the new plantings their share of sunlight.

Vince III steered the family through the addition of the juicer in 1971 and other changes. Vince IV, Noah’s older brother, works off the farm right now, while Noah oversees most of the mechanical and farming chores.

The Gizdiches have gotten creative in places, co-growing — so to speak — Ollalieberry blackberries in the same place as young Pippin trees. When the Pippins get bigger, they will take out the Ollalies, which they now use in their pie shop.

Gizdich Ranch is experimenting with several techniques to maximize growing space. Newtown Pippin trees grow amid Olallieberry blackberries, which are used in pies sold at the Gizdich Ranch Pie Shop. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

They both see a future in fresh apples in California and the Watsonville area. For one thing, apple orchards require less water than berries, which makes them more attractive after years of drought and increasing water costs, Vince said.

No large orchards have been removed in the past several years that Vince knows of, and a few are even planting new blocks with varieties coveted by hard cider makers, such as Newtown Pippins and Black Twig, he said.

“It’s not like they’ve ruled out orchards,” Vince said. •

– by Ross Courtney

I want information about Martinelli’s apples, regarding whether there is ANY presence of glysophate, i.e., GMO apples.