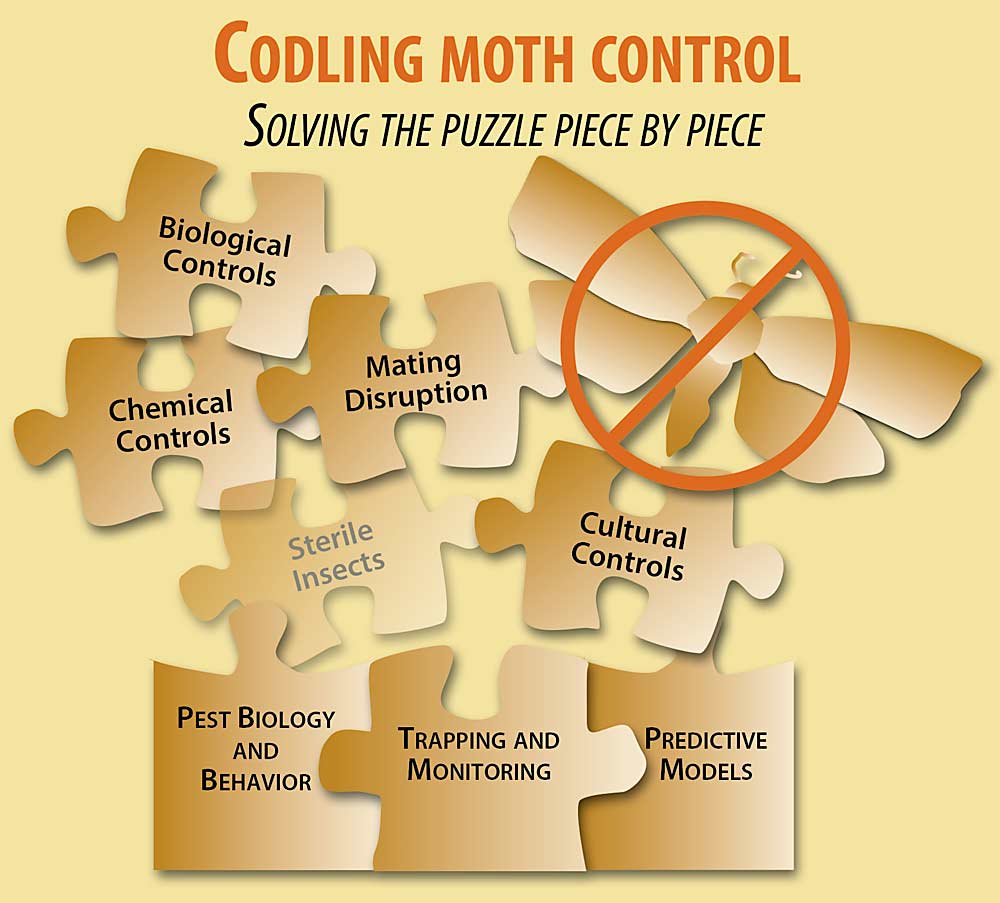

Successful codling moth control results from growers and pest consultants putting together many pieces. The leaders of a recently formed codling moth task force believe that understanding this big picture of how different aspects of the codling moth program fit together and influence each other is critical to successful IPM programs.

Some pieces, such as understanding pest biology and monitoring to assess pest pressure in individual orchards, provide the foundation upon which the rest of the control is built.

As Good Fruit Grower rolls out more coverage of the Codling Moth Summit and other stories on this topic, we hope using this piece-of-the-puzzle framework helps to show our readers how it’s all connected.

In addition to pheromone disruption and spraying, cultural controls can help to keep a lid on codling moth populations.

Orchard sanitation, bin management and netting are just a few examples, but they were the ones tackled during the Codling Moth Summit, a webinar aimed at piecing together various aspects of pest management related to one of the Northwest’s primary pome fruit pests. It was hosted by Washington State University, Oregon State University, Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission, Northwest Horticultural Council and Wilbur-Ellis.

FirstFruits targets first generation

Mark LaPierre, orchard operations leader for FirstFruits Farms in Prescott, Washington, discussed orchard sanitation, tree banding and monitoring hot spots in an interview format with Gwen Hoheisel, a WSU tree fruit extension specialist.

LaPierre uses growing degree-day models and history to target first-generation sprays. After that, trapping and scouting drive decisions.

His crews start the season with a low-density trap count in low pressure areas and keep close watch on hot spots. In hot spots, “we can’t ever seem to have enough (traps),” he said.

They do hand thinning in organic blocks, primarily in hot spots and along borders where pressure is high, physically removing fruit as soon as they start to see stings. They thin into buckets, then they dump the fruit into lined bins and dispose of it in dumpsters.

Though it’s sometimes hard to see damage, they remove fruit as early as possible to prevent the pupae from escaping, perhaps as many as two or three times in the same spots.

It’s a tough situation. Hand thinning is expensive, but you don’t know how necessary it is until you pay a crew to do it, he said.

“Invest the time and the money in the first generation, because the payback is there,” LaPierre said.

The cost is even higher for subsequent generations, because crews end up having to spray until harvest.

The company also bands trees from August through October, wrapping strips of corrugated cardboard around tree trunks to give the pest a place to overwinter. Then, the crews just carry them out of the orchard to kill the larvae and burn the bands.

They don’t band everywhere, but there are a few organic blocks and other hot spots that are consistently banded every year. In some spots, they catch as many as 15 to 20 larvae per band.

Pressure spots can be erratic. They have found areas with 30 to 40 moths per trap and, just a short walk away in the same block, traps with just one or two.

“There’s areas where they like to be,” he said. Pressure spots are often on high ground, because moths tend to fly uphill while pheromones drift downhill. They also congregate more on edges.

LaPierre’s crews throw a variety of tools at codling moth; they don’t just band or just thin. Those blocks also get some chemical control and pheromone disruption (see “Site-specific IPM”).

The goal: Keep the population low enough for mating disruption and other integrated pest management techniques to work. “We have a lot of good (IPM) strategies, but it starts to fail at high populations,” he said.

Hotter summers make controlling the first generation even more important, because the hot weather will lead to more generations. “More generations, more problems,” LaPierre said.

Consider your bins

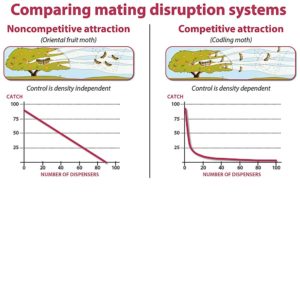

Brad Higbee, now a nut and fruit crop scientist with the pheromone company Trécé, led areawide mating disruption trials in the 1990s for the U.S. Department of Agriculture in Wapato, Washington. At the time, mating disruption was a relatively new concept and only sporadically adopted.

“We showed that mating disruption was viable both operationally and economically and kick-started mating disruption to a large degree in Washington and other areas, as well,” Higbee said.

He called the effort both a scientific and sociological project, convincing neighboring farms to share data. He managed two such projects in Wapato and Yakima, but it was repeated all over Washington, Oregon and California. The trials demonstrated the value of cooperation and data-sharing, and they reduced the use of insecticide cover sprays at least 50 percent by basing them on trap data instead of calendar days.

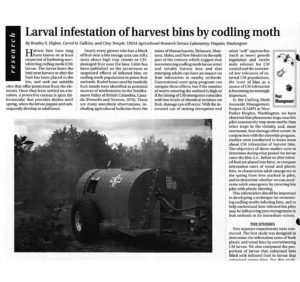

Higbee also led a project studying moths overwintering in bins. They found that plastic bins reduced moth infestation by 98 percent. “We rarely, rarely found moths burrowing into plastic bins,” he said. Whether they were empty or full didn’t make much difference.

They also found that covering stacks of bins in plastic accelerated the emergence of moths, and the timing more closely coincided with field populations. The uncovered bins had a slower degree-day accumulation and therefore a longer, protracted emergence.

Higbee suggested monitoring in and around stacks of wooden bins, because not all of them will have a population. Trap around the edges of bins and some in the interior of nearby orchards, to compare locations.

“You don’t know until you do some monitoring,” he said.

He also recommended leaving wooden bins in the orchard for as short a period as possible. Too long, and the worms make their way from the trees to the wooden bins.

Nuances of netting

Adrian Marshall, a WSU entomologist in Wenatchee, told growers that full enclosure netting does indeed work to keep out codling moths and reduce damage, but only for the first generation.

In his five years of trials at the Sunrise research orchard near Wenatchee, the few codling moths that were in his netting enclosures reproduced and caught up with the outside population by the second and third generations. His blocks had no other controls, however, which would not be the case in a commercially managed orchard.

The netting also kept out predator insects, such as lacewing, which led to more woolly apple aphids inside the cages.

Thus, he concludes netting works but only alongside other methods.

“Netting would be an effective tool in combination with other techniques for codling moth management,” he said.

Research over the past decade in France and Italy came to similar conclusions. •

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment