Colorado orchardists are no strangers to frost, but 2020 delivered a one-two punch from which peach and apple growers will need years to recover. First, a spring frost left growers with just 15 to 20 percent of a normal peach crop. Then, in an unseasonably warm October, sudden cold hit before the trees hardened off, killing peach trees across a region where it’s the top crop.

“2020 just keeps on giving,” grower Bruce Talbott of Palisade said during the 2021 harvest, as the depth of the damage became apparent.

Injured trees valiantly leafed out and set scattered fruit, only to wither in the summer heat. Signs of gummosis, from cytospora infecting winter injury wounds, abound.

“They are dead, and they don’t know it yet,” said Steve Ela, pausing to look at plum trees during a tour of his orchard.

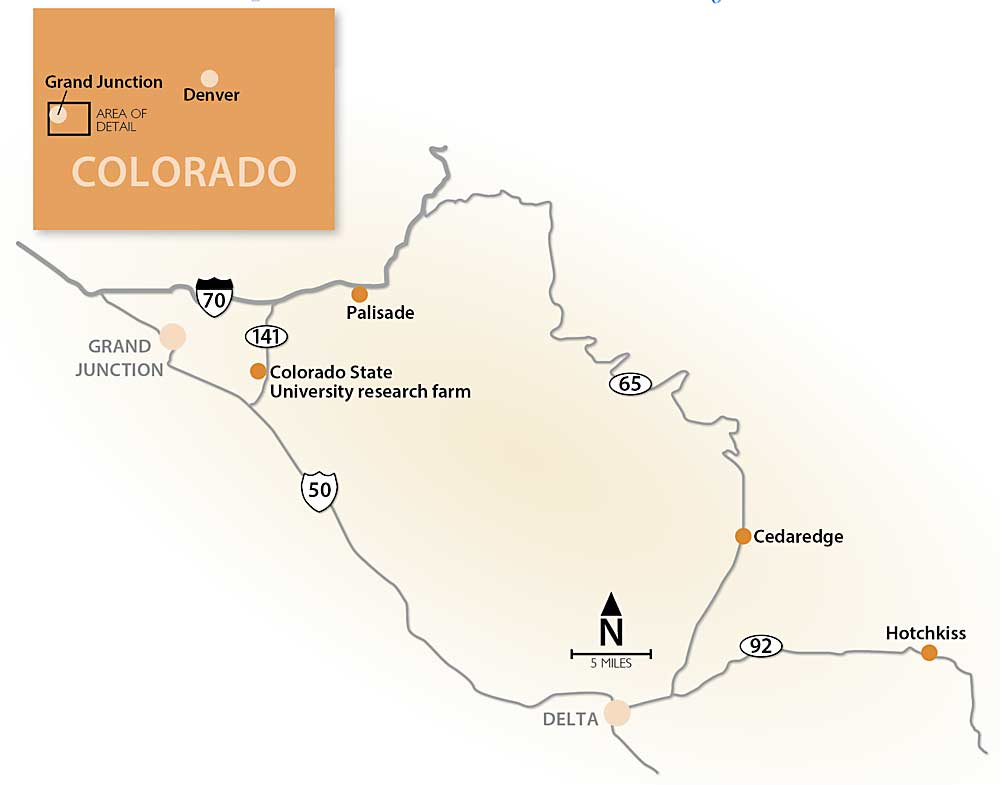

Ela’s farm, located in a high-elevation valley in Delta County, was one of the hardest-hit places, according to Ioannis Minas, a Colorado State University pomologist based in nearby Grand Junction. But across the region, the late October freeze was so devasting because it had been such a warm fall that trees had not begun to acclimate.

Ela, who directly markets fruits and some vegetables, was still picking tomatoes the day before. “The quote is that climate change sucks,” he said. “Colorado is especially hard hit because we already farm in microclimates.”

Last summer, Good Fruit Grower visited growers in three of those microclimates, representing three very different family farms as they began the process of replanting and re-envisioning the future: Ela, with 80 organic acres and farm market customers in Denver, questioning if climate change will put him out of business; Talbott, who, with his brothers, runs Talbott Farms, the region’s largest peach farm and packing operation, now doubling down on peaches; and the Williams family of Cedaredge, another high-elevation valley, who plans to pivot more acreage back to apples.

Peach priority

Colorado produces the highest-value peaches in the country, and most are grown in the Palisade area at the far eastern edge of the Grand Valley in the shadow of the foothills of the Rocky Mountains.

Here, Talbott Farms grows about 400 acres of peaches and runs a packing line for their own, and their neighbors’, fruit. Bruce Talbott runs the orchard side of things while his brother, Nathan, runs the packing house. Another brother, Charlie, is the company president.

Like most of the region’s orchardists, the Talbotts’ roots are in apple growing, but by the late 1990s, advances in controlled atmosphere storage meant they could no longer capture a premium from harvesting a week ahead of Washington, Charlie said. Peaches, on the other hand, start with an empty pipeline every season, and with the high sugars that develop from the region’s hot days and cool nights, they soon began to develop a reputation for quality.

“We have to be at market prices on apples, pears and cherries. We set our market on peaches,” he said.

Their Palisade peaches demand such a premium that a Colorado yogurt producer is willing to pay to haul processing-grade fruit from the Talbotts’ packing shed all the way to Peterson Farms in Michigan to make it into puree that’s hauled back to Noosa’s central-Colorado headquarters for its “Palisade peach yoghurt.” There’s no closer processing anymore, Bruce said.

As for the packing house, the company recently invested in new state-of-the-art sorting technology and is eying packing line upgrades that could save labor; however, it’s hard to pencil out the expenses for a line that runs just eight weeks a year, Charlie said. Labor costs, he said, follow the main challenge of climate concerns such as frosts and drought.

Still, the Talbotts had no hesitation replanting the peaches they are known for. They plan to plant 20,000 peach trees this spring, along with 10,000 vines for the farm’s 150 acres of wine grapes, which were also hit hard by the freeze.

Grapes offered a way for the Talbotts to diversify and extend their labor season to offer longer, more attractive H-2A contracts, after pulling their apples, Bruce said. They planted to serve Grand Junction’s growing wine tourism industry, but demand for grapes has fallen over the past few years.

So, the Talbotts recently started making their own wine and hard cider, all canned to target a different marketing niche, Charlie said. The efforts are led by the farm’s sixth generation, who devised a line of wine spritzers featuring — what else? — Palisade peach juice in the can and the family’s iconic orchards on the label.

It really all comes back to the peaches. Bruce will plant 40 acres this spring, at a traditional 8-by-15 spacing that will come into production in the fourth leaf and pay off the establishment costs in the sixth. He hoped to salvage some of the blocks, but “at this point, they have lots of cytospora canker and we’re better off replanting,” he said. “What hurts is that we expect to rotate out 5 percent a year, but a lot of those we lost were 5-year-old orchards.”

Replanting for reinvention

The economic success of Palisade’s peaches inspired orchardists farther east, with higher-elevation orchards, to try peaches after apple prices tanked. The 2020 freeze created another turning point, though, and the Williams family of Cedaredge is turning their full attention back to apples.

“People get excited about peaches, but when I look at the bottom line, it’s always apples that carry our business,” said Ty Williams, a fourth-generation grower who farms about 400 acres with his family. The same high-elevation climate that makes for premium peaches makes for fantastic Honeycrisp, he said.

Peaches were always on the edge of climate suitability, and after the October freeze, 80 percent had no sign of life. They also lost most of the Gala crop, but the weather didn’t faze Honeycrisp, Williams said.

Last year, he and his crew rushed to replant 100,000 trees — all apples. He planted early Honeycrisp, EverCrisp and Ambrosia, in super spindle plantings at 2,500 trees per acre. He’s also planting cider-specific varieties for Snow Capped Cider, a now-booming business he and his wife, Kari, started almost a decade ago as a hobby (see “Apple expectations”).

Ela is also reconsidering the future of his diverse fruit farm (see “An uncertain path”) following the freeze, which means pulling some surviving but marginal blocks even as he replants.

“We’re consciously contracting so we can maximize the use of our water and time,” he said. He’s getting older, climate change continues to deliver drought and unpredictable weather, and reducing risk by reducing acreage just makes sense. “We’re doubling down on trying to have a premium product,” he said.

Water worries top the list of fears for the future for Williams and the Talbotts, too. The Colorado River Basin is in a 22-year drought that some experts predict is the new normal. A compact governs the millions of acre-feet of water from the snowmelt-fed river across seven states and Mexico. The district that serves Delta County has run short in recent years, and while farmers in the Palisade area have water rights that predate the compact, ongoing shortages paired with increasing demand from urban areas puts growers’ future supply in question.

“When I was a kid, doing furrow irrigation, we learned that water flows downhill. Now, I know it flows uphill toward people in cities with money,” Charlie Talbott said.

Water is gold in their part of the world, Williams agreed. That’s why they all want to use it to grow the most valuable fruit possible — be it peaches or organics or Honeycrisp and high-demand cider apples.

—by Kate Prengaman

The frost fight

Colorado fruit growers are frost control veterans.

“We do an exorbitant amount of frost protection,” said Ty Williams, a grower from Cedaredge, a high-elevation valley east of Grand Junction. Wind machines are mandatory, but he’ll burn plenty of propane and firewood, too. “There’s rarely a spring where we are not 10 degrees below critical,” he said.

But the October 2020 freeze was an advective freeze, not an inversion, rendering wind machines useless, said Ioannis Minas, pomologist for Colorado State University.

Over the past several years, Minas and the researchers in his lab have developed cold hardiness models for four peach cultivars (representing a spectrum of hardiness) that help growers make spring frost protection decisions. Now, he’s turning his research focus to the related but distinct issue of fall/winter acclimation and how growers could manage it to reduce the impact of a sudden fall freeze and the winter injury that invites cytospora infection.

“Acclimation is a function of genotype, climate and grower management,” Minas said. “You may grow acclimating cultivars, but irrigating them in full in a very warm fall is creating tenderness.”

Trials at the CSU research farm have found both cultivar and rootstock differences when it comes to acclimation. Some California cultivars, such as O’Henry and Sierra Rich, struggle to acclimate, while Michigan-bred cultivars tend to have hardier genetics, Minas said. The rootstock Krymsk 86 and other Prunus hybrids, which are now the popular choice for replanting in the region, also need a signal to start acclimating, or they can be vulnerable.

The acclimation research aims to help growers make better management decisions, he said.

Researchers aren’t telling growers not to plant those cultivars. “I know (our growers) are forced by the market to grow specific, high-quality cultivars,” Minas said. “We are creating tools we can use to manage them so they will be sustainable and resilient in our conditions.”

One of the tools he is studying: the plant growth regulator ABA (abscisic acid), marketed by Valent as ProTone. Preliminary research so far shows it appears to deliver an acclimation signal within a few days, Minas said. That means growers could potentially use it in response to a cold shift in the forecast, to prevent a disaster like 2020.

Cutting off irrigation is another signal, but in arid Colorado, growers need to proceed with caution.

“You don’t want to dry the tree too much that you can save it from cold but stress it out from drought,” Minas said.

He recommends reducing water after harvest in mid-September. Then, when trees start to show signs of entering dormancy, usually with leaves starting to yellow, growers can irrigate again to refill the soil profile for the winter ahead.

—K. Prengaman

Leave A Comment