—by Kate Prengaman

How do you successfully farm by spreadsheet?

You make better spreadsheets.

That’s one of the top priorities for Steve Caudill, the chief technology officer at Columbia Fruit Packers of Wenatchee, Washington.

“As tree fruit matures and becomes more precision-focused, we have to work more with people who work by the numbers,” Caudill said.

He looks at data-driven farming as a new way of communicating what is going on in the orchard for the people who don’t see it every day, including both ag tech developers and new people joining the industry without decades of experience. Count Caudill among the latter.

Caudill joined the company, first in a consulting role, in 2022. He brings experience in ag tech from a previous role in precision agriculture at CNH Industrial and an outsider’s perspective on technology adoption. As part of his job helping Columbia Fruit Packers embrace the precision agriculture era, he designs experiments that produce the math needed to analyze the business.

This season, he has 20 experiments underway in the orchard and five in the packing house. Some trial new technologies, and others test to determine the most efficient and effective farming practices.

Caudill’s data-driven approach differs from a traditional approach to on-farm trials, said Tim Welsh, who has served as horticulturist for Columbia Fruit Packers for over 30 years.

“I learn stuff every year, that’s the beauty of this business,” he said. But, he added, some of Caudill’s experiments feel “designed to justify our experience” rather than test something new in the orchard.

Caudill concurs: He’s using experimental design to translate Welsh’s insights and experience so that the math, rather than the trees, can do the talking.

“Thankfully, Steve is the guy who can think through how to evaluate something and generate data to support (practices that) intuitively, I believed were not a good idea for us,” Welsh said. “We’re not as good as farmers at setting out experiments that we can actually measure.”

For example, last summer, Caudill designed a “NASCAR race” of harvest platforms, comparing Columbia Fruit Packers’ typical Washington-made Bandits with Italian Revo platforms that use conveyors to ferry the apples into bins.

The Revo platforms promised speed and quality improvements. To evaluate the latter without bias, Caudill invited quality-control staff from Allan Bros. to grade the samples. That surprised this reporter, but not Matt Miles, Allan Bros.’ process engineer.

“Bias is real, and Steve wanted to show impartiality,” Miles said. “Steve just has a different way of thinking about this stuff, which I appreciate.”

The results showed that the new platforms were slower than Columbia Fruit’s existing approach, and the packouts also weren’t as good. The imported platforms were more restrictive of movement, and they limited flexibility and teamwork the workers are used to, Welsh said.

“It (was supposed to) improve our efficiency and our packouts, but that assumes that our pickers aren’t as good as they are, that our supervision isn’t as sharp as it should be. But our pickers are good, and our supervision is great,” Welsh said. “Those platforms are very good for the farmers in Europe that operate them and are out on the platform working with the pickers, but it’s a different group of people on different farms.”

It’s a good example of how the benefits of a technology depend on the baseline conditions at every farm, and there’s no way to know how a new tool or practice change will impact your specific operation without testing it, Caudill said.

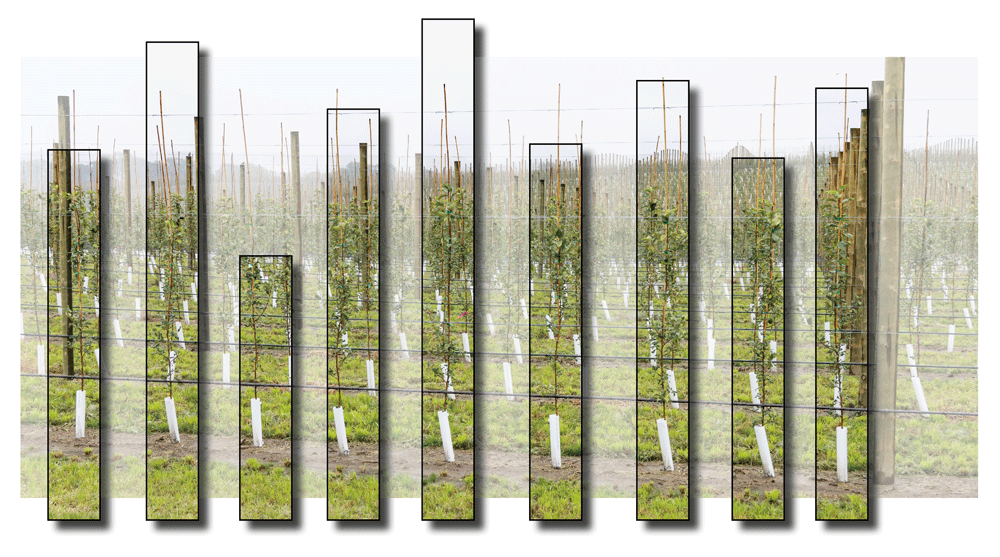

So, this year he’s using vehicle tracking tools to evaluate platform use patterns and ensure they line up with the timecard tracking data for every block; testing the Smart Apply System to see if it delivers a return on investment in high-density plantings; looking at the potential of crop load imaging tools; and evaluating the Robotics Plus sprayer, to name a few.

“The autonomous sprayer is not the experiment. Can I feed it a map that tells it how to operate, and is that meaningful? That’s the experiment; it’s not just yes or no,” Caudill said.

He has more ideas for experiments than Columbia Fruit has capacity to run them, so he aims to collaborate with other tech-minded companies. Miles, at Allan Bros., looks forward to working with Caudill again and said the wider industry benefits from the approach he has taken with technology evaluation and working with tech companies.

“We have to have conversations with the (ag tech) people who are making things, so they understand what we need,” Caudill said. •

Data-based tips

Want to embrace a more experimental mindset on your farm? Steve Caudill and Tim Welsh of Columbia Fruit Packers shared some tips:

—Recognize that experiments will cost some productivity. While doing a test run with summer interns may not replicate the results of testing a new tool during harvest, you might learn from that practice test before you put an experiment on an experienced crew with work to do, Caudill said.

—Think smaller and in stages. “You have to zoom in on what the question is. Then, you want to make the experiment as small as possible to get you what you want to know,” he said. To demonstrate, he walked through a hypothetical experiment into mowing speed. Just running the mower at 5 mph instead of its usual 3 mph and seeing that it didn’t do a great job is not an experiment, Caudill said. Instead, consider the real question: Can I mow faster? He suggests running one row at 3.5 mph. If that looks good, run another at 4. Still looking OK? Then run at 4 mph in a few different rows, with different terrain and different operators. “You might learn that 3 mph works everywhere all the time. Half the time, I could run 4 and get good results, but do I want people to take the time to figure that out?” he said.

—Prioritize. “I came up with 50 experiments, and they cut me down to 25,” Caudill said. Also, be willing to push experiments to the back burner when the season doesn’t go according to plan. As Welsh said: “Don’t try to tackle too much. That’s what we did last year.”

—Work with people who are on board and have capacity. Once the first few experiments start to yield useful information, other people will see that success and want to get involved, Caudill said.

—Focus on experiments that will alter how you make decisions. Rather than testing a technology to see if it works as advertised, Welsh’s go-to question is: “Does it help us pull a lever to improve something?”

—Don’t shy away from putting things to the test and asking for help to do so, if needed. “People have a gut feeling, and that’s very valuable, but don’t shy away from testing things,” Welsh said. “Admit when things don’t work and move on to the next thing.”

—K. Prengaman

Leave A Comment