In a rootstock trial, the differences in size, shape, and bearing capacity of a single variety on difference rootstocks is quite apparent. (Richard Lehnert/Good Fruit Grower)

At Van Acker Farms in Williamson, New York, the owners are transitioning from growing apples for processing to growing the much more desirable fresh-market varieties like Honeycrisp and SnapDragon.

Lots of growers are doing it, and some are experiencing serious problems. These weak-growing varieties don’t perform well on commonly used rootstocks like Malling 9 and Budagovsky 9.

But research at Van Acker Farms will help them and other growers identify more suitable rootstocks.

The Van Acker farming history began in 1913 when Dan and Kathy’s great-grandfather, Peter Van Acker, immigrated from Holland and purchased a 20-acre farm. Peter’s son Henry grew the farm to 75 acres.

In 1957, Henry’s son Ronald, after serving time in the military, added more acreage on which he planted not only apples but also tart cherries, peaches, and pears.

Ronald’s son and daughter, Daniel and Kathy, now work about 400 acres in the towns of Williamson and Sodus.

In 2009, Daniel Van Acker and his sister, Kathy Orbaker, donated land for a ten-year study of the performance of the Honeycrisp variety on a wide range of Geneva rootstocks. “It seemed like a good reason for a rootstock trial,” Orbaker said, considering how many growers are planting Honeycrisp. “We care for the trees, and we get to see them growing on our farm.”

After six years, the results are already dramatic. The best performing rootstock has produced more than three times the cumulative yield of trees growing on M.9 Nic 29 and has reduced biennial bearing by half.

Researchers made a big deal of the results during the Lake Ontario Summer Fruit Tour. Cornell pomologist Dr. Terence Robinson and fruit extension specialist Mario Miranda Sazo were there to present the data, and so were the current rootstock breeder, Dr. Gennaro Fazio, and his predecessor, Dr. James Cummins.

Jim Cummins, “the father of Geneva rootstocks,” who retired 21 years ago, explains why the breeding program was started.(Richard Lehnert/Good Fruit Grower)

Retired since 1993 and now living in Knoxville, Tennessee, Cummins spent time in the orchard talking about the roots of the rootstock breeding program he started while he was a professor at Cornell University in Geneva, New York. They call him “the father of the Geneva rootstocks.”

Back in 1968, he said, a bad fire blight year had just killed many trees on M.9, and collar rot was wiping out trees on MM.106 in New York’s heavy soils.

“We started thinking maybe it was time to start making rootstocks for New York and not for England,” Cummins said.

All the Malling and Malling-Merton rootstocks then available were selected in England based on their performance there.

The early goals of the Geneva program were broad—finding fire blight resistance, crown and root rot resistance, and rootstocks capable of fending off replant disease without soil fumigation.

“We were not as ‘scion tuned’ as we now are,” Cummins said.

Designer rootstocks

Robinson said that was one of the key features of the Van Acker trial: Dozens of rootstocks—some still being evaluated for potential release—are being tested for their performance on this one variety.

“We need to look at smaller things,” Robinson said. “Our goal should be to create a designer rootstock for a specific variety and a specific location.”

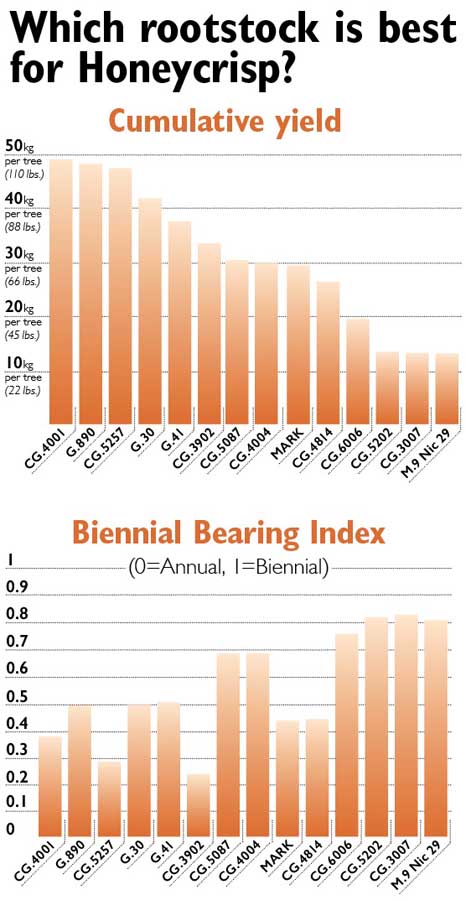

Van Acker Rootstock Trial with Honeycrisp, planted 2009, data through the sixth leaf. Source: Cornell University (Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower)

The data in this trial should easily steer the Van Ackers to G.890; the other top performers have not yet been released for commercial use.

In the trial at Van Acker Farms, the top performing rootstocks for cumulative Honeycrisp yield were CG.4001, G.890, CG.5237, and G.30, all of which produced from 100 to 125 pounds per tree through their fifth leaf.

By comparison, M.9 Nic 29—the most vigorous of the M.9 clones and best suited for weak-growing cultivars—produced about 50 pounds.

“With an expensive variety like Honeycrisp, that’s $50,000 to $70,000 per acre in lost income over six years,” Robinson said.

Evaluated on an index of biennial bearing, M.9 Nic 29 rated 0.8, with 1 being the worst possible, compared with 0.3 to 0.5 for CG.4001, G.890, CG5257, and G.70. In the tests, biennial bearing and lower cumulative yields paralleled each other.

On another measure, average fruit size, rootstock did not appear to have a large effect. Robinson noted that, in the case of Honeycrisp, finding a rootstock that would reduce fruit size might be desirable.

Cummins’ career as a rootstock breeder was undertaken with a plant pathologist partner, Dr. Herb Aldwinckle, and the two evaluated some half-million rootstocks. In the selection process, the rootstocks were challenged with diseases, and those that failed were eliminated from the tests, no matter what other virtues they might have. “We killed a lot of trees,” Cummins said.

When Cummins retired, Cornell sought increased financial help from its longtime partner, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and the program continued as a joint venture with Fazio as the rootstock breeder.

Much of his work focuses on evaluation of rootstocks bred and selected by Cummins and Aldwinckle.

After retiring, Cummins started Cummins Nursery, in Ithaca, New York, now run by his son, Steve. •

Leave A Comment