It was May 20, with a little more than a week to go before Youngblood Vineyard was scheduled to open on Memorial Day weekend. Co-owners Jessica and David Youngblood had been working most of the day in the mad scramble to prepare, and they would be working most of the coming days until everything was ready.

“We don’t feel ready yet, but we will be,” Jessica said.

There was a lot to do at the vineyard and outdoor winery in Ray, Michigan, about a 35-minute drive north of Detroit. With help from their three teenage children, they had to mow the mustard plants and move giant tree trunks in the parking lot, set up tables for extra seating and a dance floor and tent for a high school prom, stack lumber in stylish racks near the new pizza oven, figure out how their new tractor and sprayer worked — not to mention the dozens of other tasks that had to be performed.

And then there’s the perennial task, the thing that makes Youngblood Vineyard unique in the region: maintaining its 25 acres of cold-hardy wine grapes.

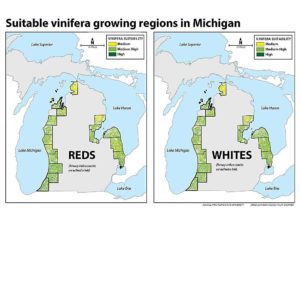

There are plenty of wineries in metropolitan Detroit, but actual vineyards are scarce. In Michigan, most traditional Vitis vinifera varieties grow on the west side of the state near Lake Michigan, which offers some protection from killing freezes. Southeast Michigan offers no such protection. Growing cold-hardy wine grapes from Minnesota — in Youngblood’s case Marquette, Petite Pearl, Itasca, Prairie Star, Frontenac and Frontenac Blanc — is the only way a vineyard can survive in the Detroit area. And even that’s not easy. Spring freezes killed most of their buds in 2020 and 2021, Jessica said.

Despite those disappointing losses, there have been bright spots for the new business. Youngblood’s Marquette wine was named best dry red wine in Michigan in 2019. Hour Detroit magazine named Youngblood the “Best Place to Drink Outdoors” in 2020, and “Best Winery” in 2020 and 2021.

And Jessica still has great faith in cold-hardy varieties and the role they can play in the future of Michigan wine. She thinks cold-hardy varieties will allow the state’s vineyards to spread beyond the Lake Michigan coastline and push past traditional climatic barriers, creating new opportunities for Michigan wineries.

On the other hand, starting a vineyard and winery is neither easy nor cheap, as she knows from personal experience.

Winding road

The Youngbloods took a long, circuitous path to growing wine grapes in Michigan. David grew up in Georgia, Jessica in Washington state. The two of them met while attending Walla Walla University in southeastern Washington and working in the health care field in nearby Oregon. They spent the next 15 years moving — a lot. Many of the moves occurred after David joined the U.S. Marines. Along the way, they were married and had three kids. By Jessica’s count, they’ve lived in eight states — some of them, like California, known for wine grapes.

They settled permanently in Michigan in 2015 on 40 acres of farmland that have been in David’s family since 1945. David visited the farm frequently as a child, where his grandparents grew soybeans, corn and Christmas trees.

The Youngbloods and their kids had fallen in love with Virginia’s wine country while living in Washington, D.C. Jessica thought it would be cool to grow wine grapes in Michigan. David told her about the cold-hardy grapes he’d heard about while studying law in Minnesota. They did some research and decided to make the leap and start a fully estate-grown winery.

They realized that the only way to make it as a small farmer is to add value to your crop, David said. A few decades ago, apple farms in the Detroit area got by selling bins of apples, but these days they get by selling wine and cider. The Youngbloods decided to go in the same direction.

There was a lot of work to do. They had to clear acres of overgrown Christmas trees, install a fence around the property and grade the land before they could even start planting grapevines. They first planted 12 acres in 2016 and now grow six varieties on about 25 acres. In the first four years, spring frosts didn’t damage any grapes. But just as they were close to getting a full crop, they’ve had two consecutive bad springs. They lost about 80 percent of their crop in 2020 and will probably have another big loss in 2021. They were still assessing the damage in May, when Good Fruit Grower visited.

Jessica said Petite Pearl, a cold-hardy grape from Minnesota breeder Tom Plocher, has been the lone bright spot the past two years, suffering no freeze damage because it buds out later than the other varieties. Still, for a small winery that supplies all its own wine grapes, freezes can be devastating. They have to limit wine sales this year because of last year’s short crop, and they will probably have to do the same again next year.

“You can only go through so many years of that,” she said. “It’s frustrating, because a polar vortex has nothing on these grapes. But with spring frosts, there’s nothing you can do.”

They opened the second phase of their business, the outdoor winery, in 2019. It was a simple affair — an outdoor bar, pavilion, couches and other seating where customers could hang out and drink wine in a peaceful setting. This year, the Youngbloods added a pergola and pizza oven. They also host on-farm events such as weddings, dinners, proms and “tiny goat yoga” (regular yoga, but with tiny goats prancing about), which became especially popular during the pandemic. The winery’s outdoor-only focus made it very easy to adjust to COVID-19 restrictions, Jessica said.

All along the way, Jessica and David have received help from their three children: Georgia, 16; Gracie, 14; and Wyatt, 13. Wyatt has been leading vineyard tours for the past three years. He said he was nervous at first, but the more he did it and the more knowledge he gained, the more comfortable he became.

“I like leaving people with more knowledge than they came,” he said.

His mother said Wyatt loves growing and has his sights set on an agricultural college.

“I don’t know if that would have happened if he hadn’t grown up on a farm,” Jessica said.

Like her son, Jessica is passionate about the educational side of vineyards and winemaking. She’s a board member of the National Grape Research Alliance, the Michigan Wine Collaborative and other industry groups. She’s hopeful about the future of the Michigan industry, and of her own winery. At the very least, she feels sure her family has finally settled down.

“I think this is the longest we’ve lived anywhere,” she said. “I don’t see us moving again.”

—by Matt Milkovich

Leave A Comment