Direct-market farming is often portrayed as a highly profitable alternative to row crops or a way to work very hard for very little money.

For people who want to start their own orchards, direct marketing is often seen as an entry point.

Growers who want to sell their apples on the farm or at farmers’ markets have a smaller initial investment than wholesale producers, due to smaller land and equipment requirements.

A direct-market orchard can be planted anywhere there are enough customers to buy the products, as long as the land has the right soil and climate.

While direct marketers can sell their products for a much higher price than wholesalers, they also face higher overhead and labor costs, and there are the underappreciated costs of selling their products.

The long-term viability of these small farms depends on whether or not they can recoup their investment and make a yearly profit.

Since 2009, instructors working for the Minnesota State Colleges and Universities have been collecting data from small, direct-market fruit and vegetable growers to determine both the cost of production and the whole farm profitability of high-value crops.

Crops included in the study included pick-your-own strawberries, mixed vegetables and apples. The costs of production and profitability of all three crops were very similar.

To determine the cost of producing apples for direct markets, I selected four farms in eastern and southern Minnesota that are representative of small, Midwestern, direct-market apple orchards.

The owners of these farms bought land and planted trees while still holding a full-time job. Three farms sell the majority of their crop from on-farm stores, while a fourth farm sells primarily at farmers’ markets.

Wholesale accounted for less than one-quarter of all sales for each farm. All farms primarily use Malling 26 and Budagovsky 9 rootstocks and grow an average of eight varieties of apples.

Three of the four farms raise other fruit for direct-market sales, but apples account for the majority of their sales.

The orchards ranged from 4 to 12 acres, though farm sizes changed during the seven years of the study as growers either expanded or reduced their acreage.

The oldest farm was 30 years old, while the youngest farm was 5 years old at the start of the study.

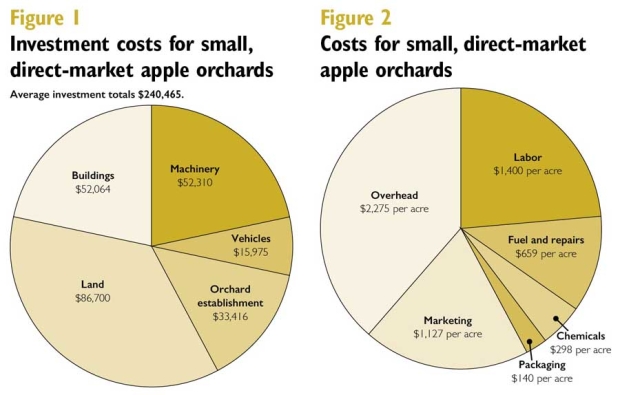

The growers invested an average of about $240,500 from the time they bought the land until they started selling apples (Figure 1).

Prospective growers usually worry about the cost of trees and land, but for these orchards, land and orchard establishment (trees, irrigation and deer fences) accounted for only half the investment. The rest of the investment was in buildings to sort and sell their produce, vehicles to deliver their apples to farmers’ markets, and orchard equipment.

The participating growers sold an average of $8,226 worth of apples per year. The lowest receipts were $2,562 per acre, while the highest receipts were $16,630 per acre.

The average yield of sold apples was 160 bushels per acre.

The low average yields were due to a combination of factors, including two years with frost, one year with hail, alternate bearing, recently planted trees, and apples that were either left on the tree for lack of market or knocked to the ground by careless customers.

An acre of apples costs about $5,900 to grow and pick. The largest single cost was labor, at $1,400 per acre (Figure 2).

All the growers who participated in the study do most of the pruning and tractor work themselves, and unpaid family labor was not calculated here.

Farms with less than $20,000 in sales can get by without hiring labor. Overhead costs averaged $2,275 per acre, and varied little between farms.

Overhead costs include farm insurance, property taxes and equipment depreciation.

The largest overhead cost was miscellaneous supplies, which is also known as “trips to the hardware store.”

With an average annual profit of $2,324 an acre, and an average of 6 acres per farm, growers are being paid little for their own labor.

When gross sales were less than $5,000 an acre due to frost or hail, the growers earned nothing. In good years, growers made $15 to $30 an hour for their orchard work.

When expenses for the entire farm are analyzed, which includes pumpkin sales and other crops, the participating growers made a whole farm profit of $13,474 per year.

The return on investment varied from 1.2 percent to 6 percent. The farmers are barely able to pay themselves, but they continue to farm.

All the growers work very hard for low profit, but their net worth is increasing each year. The increases in net worth during this study were from paying off loans or buying assets and did not include increases in land values during the course of the study.

Even without incorporating increases in land values, the average farm had an increase in net worth of $23,400 per year.

Unfortunately, an increase in net worth does not buy groceries, but all the farmers have a spouse with an off-farm job.

In spite of the low profit, every grower continues to farm due to a variety of personal and financial goals. The apple orchards have given the participating growers a way to live a rural lifestyle, to provide jobs for children and other relatives, and to pay off property.

Most direct-market growers are farming one-third of the land that they own, with their remaining land being in forests or being rented out. The extra land increases overhead costs and decreases profits, but I have yet to meet any farmer who wants to sell their 20 acres of forests.

Direct-market apple production can be profitable, but it is a great deal of work, and it helps to have a spouse with an off-farm job.•

—by Thaddeus McCamant, Ph.D., a specialty crops management instructor and freelance writer based in Frazee, Minnesota.

I was hoping there was going to be a comparison to smaller farms that market completely wholesale.

This is a very limited study, by the author’s own admission some of these orchards are not yet fully productive (immature orchards don’t produce nearly to their potential). There are only 5 farms investigated and at least one of them isn’t in full production. This is not an insignificant oversight. Additionally, the notion that the farmer should maintain a full time job off farm while simultaneously hiring on farm help is beyond comprehension. If you intend to farm, be a farmer full-time. You’re time is your greatest asset and your labor costs your largest overhead. You should always investigate if increased labor costs justify scaling up your operation. Don’t try to treat your farm like a growing corporate giant, treat it like a small family business and become competent at your niche farming enterprise.

It’s also worth keeping in mind that it doesn’t make sense for a farmer to pay herself a large wage. Obviously income is taxed at an extremely high rate while money reinvested into the farm/business/family is not, it is disingenuous to act like farmers are paid starvation wages when we obviously have incentive to structure our finances in such a way that all profits are reinvested. There is also zero tax incentive for any farmer to claim a net profit in any more than 2 out of 5 years. The idea that increases in net worth are somehow insignificant compared to the wages earned by a farmer is silly, the farmer is a business owner and the gains in net worth are his (and untaxed). Also, you are a farmer, quit going to the grocery store. You can make money farming, we need more people to get into farming, don’t try to emulate the models of larger operations you do not need 50k worth of equipment for a 4 acre orchard, that is ridiculous. Make sure your investments (both in equipment and labor) are scale appropriate.

George I would love to speak to you more in depth. My family and I are going to be starting an apple orchard soon on our land and you seem to have a lot of knowledge and common Sense and I wouldn’t mind picking your brain about a few things, hope things are going well and God bless.

That 50k might get you a tractor, or 2/3rds of a new truck haha