Drones stoke the sci-fi imagination about the future of farming.

Hyperbole and fascination abound, but unmanned aerial vehicles have become part of commercial reality for some niche applications. Growers are using the tools for tasks such as insect release and imaging, and spraying in small amounts is not far off.

“We’re looking at how do we take (drones) and — not revolutionize the industry — but just take something that we all know how to do and make it a little bit better, make it a little bit more cost-effective, make it a little bit easier,” said Jeff Allen of G.S. Long Co. at a drone field day in Pasco, Washington, organized by Washington State University.

At the field day, G.S. Long and several other vendors joined WSU researchers to discuss equipment and provide demonstrations over nearby apple and cherry trees for a dozen or so growers who watched with a mixture of interest and skepticism.

Insect release

One area where drones have taken hold commercially in the tree fruit industry: insect release.

M3 Agriculture Technologies uses drones to release sterilized codling moths over about 4,000 acres of Washington tree fruit, said Nathan Moses-Gonzales, the CEO of the startup. The company has also recently entered the beneficial insect release market.

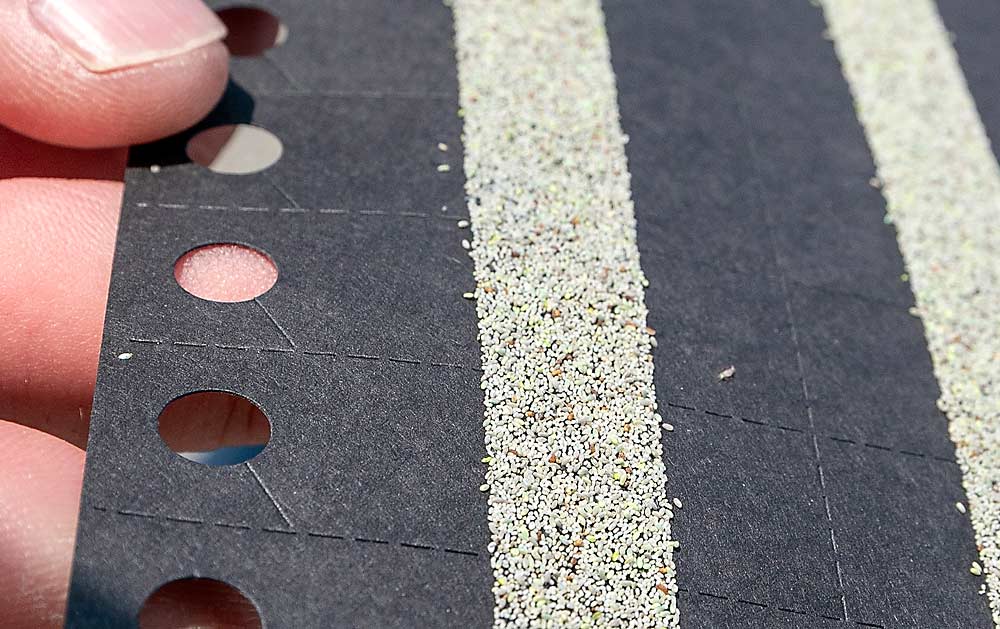

G.S. Long, the ag services company based in Yakima, Washington, chose to concentrate on beneficial insects. Operators use DJI Matrice 600 Pro and Agras T10 drones to release lacewing, ladybugs and predatory mitesfrom a cylindrical emitter with adjustable holes made by Parabug, a Salinas, California, manufacturer.

In 2023, G.S. Long’s third year of drone releases, the company plans to treat about 3,500 acres. “We’re looking forward to seeing that grow,” said Aaron Avila, grower services director.

The other option is to hang cards with eggs by hand. Drones are faster, but many of those eggs fall on the ground, so operators use a higher rate of release from the air.

Stemilt Ag Services contracts G.S. Long’s drones for predator release because they are faster and disperse more evenly than hand releases, said Robin Graham, general manager.

“By drone, we’re really able to get them spread out to that desired number per acre,” he said.

The drones also take archival video of the insect releases.

So far, Stemilt has chosen not to invest in its own UAVs. The company only schedules a few releases per year, when its integrated pest management program needs a boost, Graham said.

The company has experimented with drones for imaging but so far prefers the variety and quality they get from fixed-wing aircraft. The managers also examined spraying with drones, but they found the company sprays too frequently and too much to make it feasible, he said.

Graham expects drones will perform more tree fruit work in time, as the range and the payload capacity improve.

The elusive spray niche

Bill Kuper, owner of Ag Drones Northwest, sprays with drones for one Walla Walla, Washington, client with a vineyard so steep it’s hard for tractors, and even workers with backpack sprayers, to reach.

But drones only carry so much at a time. The DJI Agras T30, a common choice for spraying, can cover 25 acres per hour, assuming a 3-gallon-per-acre application rate. The craft has a 30-liter payload capacity. Batteries need to be swapped every 10 minutes or so.

However, he expects more capabilities in the future as technology for drones improves each year, just like it did for smartphones.

“If you can do 30 acres an hour today, a year or two, you’ll do 60 or more,” he said.

Kurt Beckley of Altitude Agri Services offers spray and drying services with his drones. He considers drones useful for “niche” tree fruit applications, though he has no industry clients yet. Drones can carry only a fraction of the needed volume, limiting their value over large areas.

“Unless we flew the acres multiple times with multiple drones,” he said.

He is applying for Federal Aviation Administration permission to “swarm,” or fly multiple drones at a time with one controller.

Kuper and Beckley demonstrated their UAVs at the WSU field day.

Reid Donaldson, a horticultural technician at Mount Adams Fruit, attended the field day and said he’s curious about the beneficial insect release but is so far underwhelmed by the idea of spraying by drone. The tools cost upward of $40,000 each, plus the trailer to haul them and two people — a pilot and a spotter — to operate them.

The spray drones carry about 8 gallons of fluid, but tree fruit applications usually require 100 gallons per acre. That would mean a dozen refills each acre.

Even if capacity improved to 50 gallons, drones still would only help for spot spraying, something he would just as soon send a tractor to do.

“A tractor will last 30 years,” he said.

G.S. Long, the company making insect releases, would like to take its drone work into the spray arena, both on orchard trees and on irrigation ponds to mitigate algae, Avila said. But the company is waiting for more regulatory clarity. For example, some product labels restrict boom angles and types of nozzles. The company also is experimenting with pollen application but still needs to work out some mechanical kinks with the application process.

Imaging making headway

Several imaging companies are offering their services to Northwest orchards and vineyards.

Aerobotics, a South African company that opened in the United States in 2019, has about 15 tree fruit clients with a total of 12,000 acres in Washington. It serves about 500,000 acres worldwide, said Sean Oliveri, who leads the company’s U.S. operations.

The company, which did not participate in the field day, flies a DJI Matrice M210 with a MicaSense sensor to determine overall orchard characteristics, such as vigor, transpiration and tree count. Based on that data, algorithms recommend representative spots for growers to physically count fruit on a single tree, from the ground, and use a phone app to measure fruit to calibrate.

Put the metrics together and, within 36 hours, a grower has an estimate of yield and sizing for each block that should inform a host of management decisions.

A Washington company, Tyton Aviation, aims to generate that same crop load information without any hand counts, said owner Aaron Tyler, who did speak at the field day.

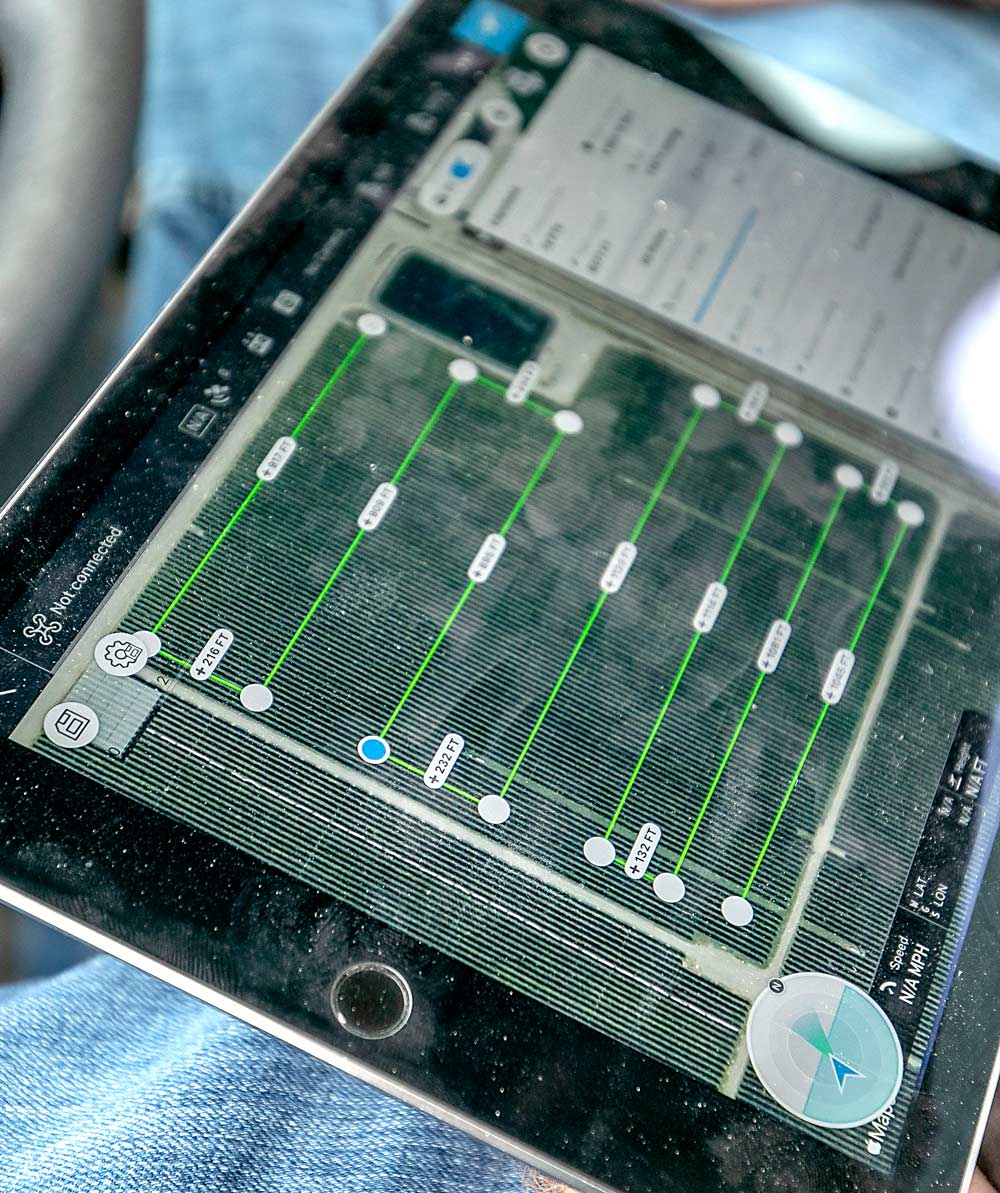

So far, a couple of growers have allowed him to test the waters for bloom and fruitlet density mapping on roughly 120 acres near Chelan and Brewster, though he has no paying customers yet. He flies his DJI Air 2S drone in zigzag patterns over the blocks, aiming sensors at 45-degree angles.

The goal is to get a visual of every tree and turn that into yield estimates to inform crop management decisions, such as thinning, bin staging and scheduling labor. He teams with a data collection software company called Outfield.

WSU ag engineer Lav Khot and his team have researched the use of drone imagery to understand crop water use, spot diseases and irrigation problems, and evaluate the frost mitigation efficacy of wind machines.

They also are seeking an FAA license to spray with drones. Part of their research will measure spray efficacy and drift with existing spray booms, aiming to re-engineer and redesign the booms for modern orchard systems.

Overall, Khot takes a skeptical approach to the commercial use of drones in the tree fruit and grape industries. He believes entrenched service providers, such as G.S. Long or Wilbur Ellis, are the best bet because they have a history of working with growers every day and will know when a drone is the right tool for the job — and when it’s not.

Beckley of Altitude thinks drones have more capabilities and applications than researchers give them credit for. They can spray in niche amounts, dry effectively and pollinate.

“Having spent as many days in the field as we have, we know that a lot of the things that they’re skeptical about are possible,” Beckley said. “And we just need the opportunity to be able to prove it.”

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment