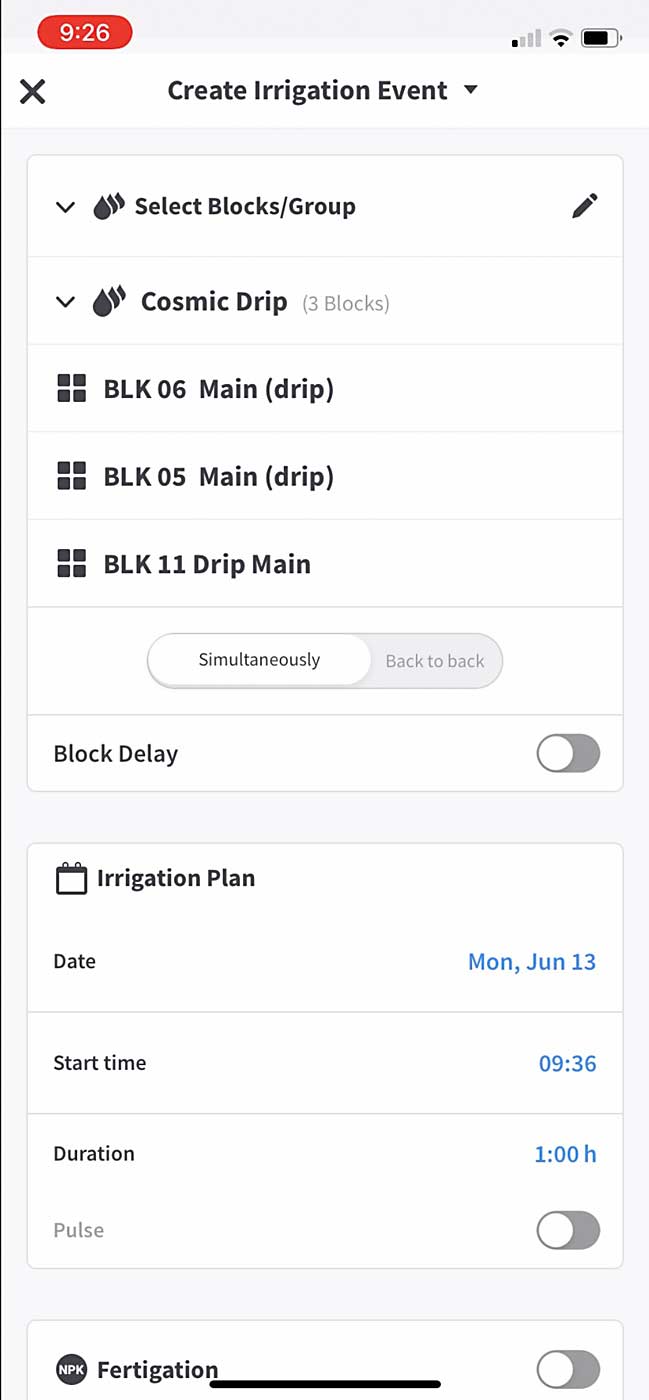

With a tap on an app, the drip starts to drop.

Automated irrigation technology is becoming a reality in Northwest tree fruit orchards, reducing labor costs and enabling new approaches to irrigation.

“We’ve reduced water dramatically and do shorter sets more frequently,” said Cody LaRiviere, an orchard manager for Washington Fruit and Produce Co. While they used to run two three-hour sets each day, they have found better responses — in terms of fruit quality and size — from cycling shorter sets.

The ability to schedule those sets in the app and have them run automatically allows growers to plan irrigation based on plant needs, not people’s schedules.

LaRiviere spoke about converting the orchards he manages to automated irrigation during a virtual orchard meetup in June, organized by Washington State University, Michigan State University and Cornell University to talk about labor-saving technology.

He gave Good Fruit Grower a tour of the automated system set up in a WA 38 block in the Columbia Basin — one of the first places Washington Fruit decided to trial the technology last year. It makes the most sense to deploy the automation hardware and the plant-based water stress sensors they use to inform irrigation decisions in cultivars such as Honeycrisp and WA 38, where controlling fruit size and vigor plays a role in disorder management, he said.

“Early on in the season, we want the trees to grow, so we give them 80 percent of capacity,” LaRiviere said. “Once we hit about the first week of June, we start deficit irrigating.”

For deficits, he’s aiming for 60 to 70 percent of field capacity for WA 38 and 40 to 60 percent for Honeycrisp, depending on rootstock and soil type. While soil moisture probes measure field capacity, sensors from Phytech monitor trunk and fruit growth rates to ensure the deficit irrigation hits the desired targets.

“With this technology, you can see the trees stressing out before the trees show signs of stress,” LaRiviere said. “Once you see the physical evidence, you’re behind the eight ball.”

Since implementing the sensor technology three seasons ago, he’s improved the packs per bin for Honeycrisp, he said. (New shade cloth and mist cooling have contributed to the increase as well.) By tracking fruit growth, he can irrigate to hit the 72–80–88 size targets, minimizing losses to bitter pit. The automation technology enables more frequent irrigation sets, giving the trees just what they need, when they need it, and no more.

Phytech provided the sensors and irrigation recommendations, and the company installed the automation technology known as DropControl, developed by WiseConn Engineering. WiseConn provides its systems to irrigation distributors who can then install the equipment as a standalone automation system or in conjunction with sensors and apps from Phytech, Semios or others.

“We don’t do agronomy, we just do the automation,” said Guillermo Valenzuela, vice president of sales and marketing for WiseConn. The California-based company has distributors in South America, Mexico and Australia and recently expanded into the Pacific Northwest.

The DropControl system consists of monitoring sensors and control nodes, which are the brains of the operation, remotely controlling pumps and valves. All the pieces talk together via a radio mesh network, so that if a flow meter detects a sudden jump in flow or a pressure transducer detects increased pressure, for example, if a drip line breaks, the control node will respond by closing the valve to that segment of the system.

“The system has that safety because it’s constantly communicating,” Valenzuela said. That field communication requires no cell signal, thanks to the radio network. One node, called a gateway, is placed in the location with the best reception on the farm and synchronizes the system with the cloud. The amount of data transferred over the cloud is relatively small, so growers can still schedule irrigation with a spotty signal, but there may be a bit of a delay in those cases.

Automation gives growers the advantage of scheduling in off-peak hours to save energy costs, which is big in California, or in short, frequent bursts in light soils, to ensure growers waste no water, Valenzuela said. He’s known almond growers to run 10 20-minute sets per day. Automation also can aid in properly injecting fertigation, he said.

Once water systems can be operated remotely, the door opens to automatic cooling or frost control when orchard temperatures cross a certain threshold.

“You don’t have to have somebody out there on a Sunday. We send the alert and they can start the system,” remotely, he said.

Growers can even opt to have cooling or frost water systems triggered automatically at temperature thresholds. But in those cases, growers must sign off against holding WiseConn liable if there’s ever a problem, Valenzuela said. Most growers prefer to start the system themselves via the app, so they can ensure that the ponds are full, pumps are operating, and so forth.

At Washington State University, WiseConn’s automation technology is helping extension specialist Bernardita Sallato closely monitor trials on vigor management and heat stress. She had the system installed in a 1-acre WA 38 block at the Roza research orchard in Prosser, at a cost of about $9,000 for the hardware.

“The good thing about WiseConn is that you can plug in different sensors for moisture, temperature, EC and others, from different providers,” she said. With funding support from the WSU-led AgAID institute to advance the use of artificial intelligence in agriculture, she’s installing more sensors in the block to create a technology demonstration and “ground truth” how the different sensors work for irrigation scheduling.

There’s still a lot to learn about precision irrigation strategies, but the automation technology already provides real-time data in the orchard for precision management, Sallato said, which is key for improving fruit quality and packouts, especially in high-value cultivars such as Honeycrisp. In sandy soils, she said switching to more frequent, short sets can “reduce the water use, reduce nutrient loss or nitrogen leaching and provide a better control of fruit growth.” •

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment