A decade and a half after horticulture researchers at Virginia Tech embarked on an effort to model precision blossom thinning, growers there and in other parts of Eastern U.S. apple country will finally have a chance to try it out.

The model — originally developed for organic growers in Washington who wanted more precision for blossom thinning with lime sulfur and oil — will be available this year on the NEWA system, the Cornell University-run weather station, Network for Environment and Weather Applications, that provides weather data and best management practice models across the Eastern U.S.

The timing aligns with new labels that allow lime sulfur to be used for blossom thinning for the first time in Pennsylvania, Virginia, North Carolina and New Jersey.

Blossom thinning presents uncharted territory for most growers in the region, said Jim Schupp, horticulturist at the Penn State Tree Fruit Research and Extension Center in Biglerville, Pennsylvania, as past experiences with Elgetol and other products were deemed too risky. But his own research using the model and thinning with lime sulfur and oil suggests that it could be a valuable tool for growers in the Mid-Atlantic.

“The earlier you remove the competition on the tree, the better you get fruit size and return bloom, so there are compelling reasons to use bloom thinners,” he said. “From some of the conversations I’ve had with growers, I’m pretty sure there are folks who are going to give it a try to improve return bloom on Honeycrisp or better fruit size on Galas.”

To introduce growers to blossom thinning, Schupp organized a workshop as part of the Mid-Atlantic Fruit and Vegetable Conference in Hershey, Pennsylvania, January 29 to 31.

Follow the pollen

Although the model was developed for Pacific Northwest growers, thanks to funding from the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission, it should work just as well in the East, said Virginia Tech pathologist Keith Yoder, who led the project to develop the pollen tube growth model.

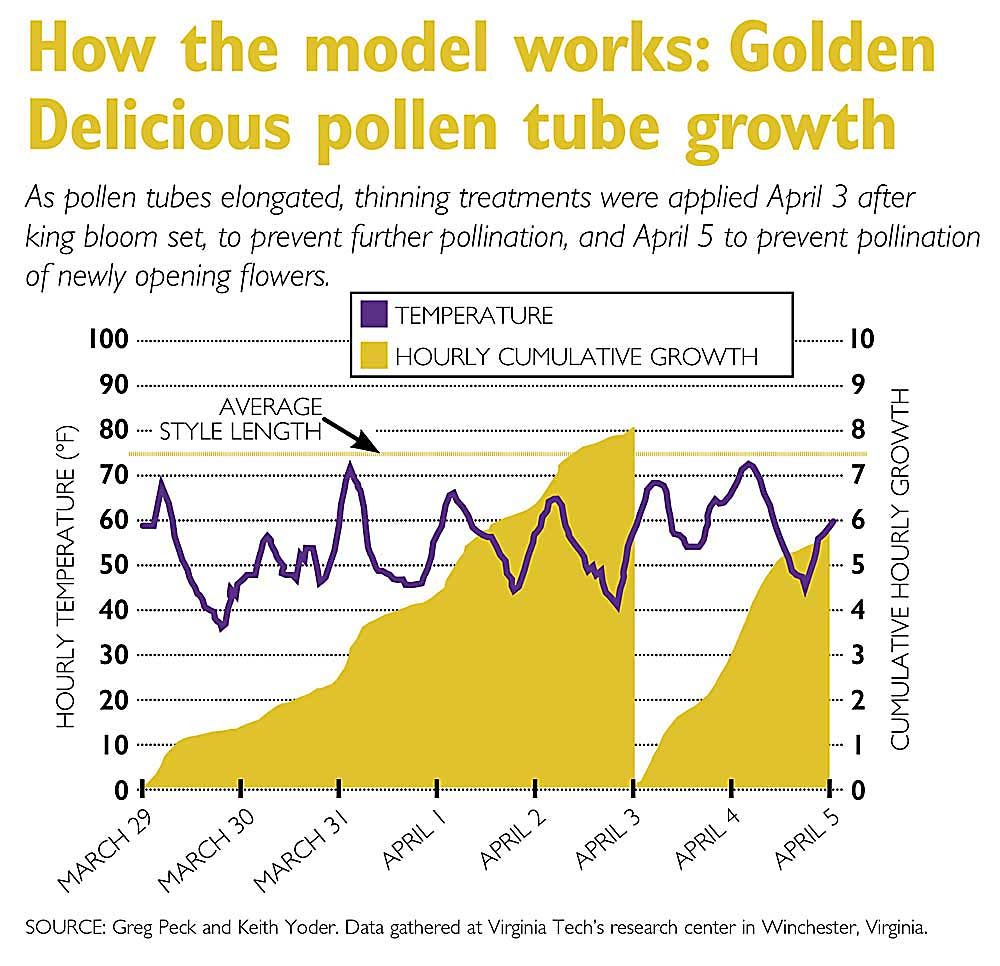

He and his colleagues carefully measured the growth of the pollen tube down the style in apple blossoms, under different temperature scenarios, to understand how weather affects the timing of fertilization.

“The model tracks the last blossom that you want to be part of your crop, and when that theoretical flower gets fertilized, you spray to set your crop,” Yoder said. After early king bloom, the model helps time further sprays for side bloom and later clusters, if necessary, to ensure no more fruit is set.

The model can predict pollen tube growth in Gala, Golden Delicious, Cripps Pink, Fuji, Honeycrisp, Granny Smith and Red Delicious. It’s temperature-dependent, similar to NEWA models for disease or pest pressure, which is how pathologist Yoder got involved in this horticultural project in the first place.

The data comes from trees grown in root bags to keep them small enough to be moved from the field to temperature-control chambers at the Virginia Tech research center in Winchester, Virginia.

Yoder said he’d like to see the model developed for a few other important varieties in the East, such as scab-resistant Gold Rush and Ginger Gold.

To get the most accurate results from the model, it’s important to measure the style length from a sample of the block. Style length varies by variety, but also within a block and from season to season, Yoder said. “It sounds like a pain, but I can get an accurate representation of average style length in about five minutes with vernier calipers,” he said.

If there is a NEWA station nearby, it will be easy for growers to run the model and find out where they are in the pollen tube growth process. But Yoder cautioned that in the rolling hills that are home to apple orchards in Pennsylvania, Virginia and West Virginia, more blossoms could be open higher up on the hill than at the bottom, thanks to differences in night temperature.

“Thinning is an art, regardless of how you do it,” Yoder said, but this model adds more science to the process than just blasting the trees at approximately 20-percent bloom and 80-percent bloom and hoping that sets the right crop, he said.

Trying it out

Schupp has been experimenting with lime sulfur for blossom thinning for more than a decade, in New York’s Hudson Valley and in Adams County, Pennsylvania. He was convinced it could be a valuable tool for growers, but the regional manufacturer of lime sulfur declined to pursue a label for thinning use, so the research effort went on the back burner.

Until recently, that is, when manufacturers applied for labels in the Eastern states. While demand from organic growers is small in the region, the benefits of blossom thinning for fruit size and return bloom intrigue many conventional growers, Schupp said.

So, last year, he resumed his trials and used the pollen tube model to time sprays for Honeycrisp and Gala blocks in Biglerville. More trials are needed to determine the ideal application rate and how it can be used in coordination with other crop load management strategies, he said.

In 2018, “we had to put our second spray on in 24 hours from the first one, because the weather was so very warm right at that particular part of the season,” he said. There’s a risk that such successive applications could end up putting too much lime sulfur on the trees, causing fruit growth to lag. Lime sulfur can also burn foliage.

“It could be that we make one application (of lime sulfur and oil) and then look to our postbloom strategies to finish the job,” Schupp said. “We just need more time and experience with it.”

Of course, the weather doesn’t always cooperate for current carbaryl thinning practices either, Schupp added. Typically, the technique works much better in the East, where more cloud cover means carbohydrate deficits that growers can exploit to cause fruit drop after they are confident a sufficient crop has set. But, with variable spring weather, “you can wait for something that never shows up as far as effective thinning windows,” he added.

That’s why having a variety of tools at a grower’s disposal is so appealing — although some growers who want to export to Europe also need a noncarbaryl thinning program, as well.

Another aspect in need of more research: the potential to tap into the disease control benefits of a lime sulfur and oil thinning program. Yoder said that lime sulfur controls both scab and powdery mildew, while Regalia and JMS Stylet-Oil together provide excellent rust control. Regalia also shows potential as a blossom thinner, in Yoder’s research trials, but the manufacturer has not pursued labeling it for that purpose.

“A couple times in a week (for thinning) is a tighter schedule than we would do for disease control,” he said, but bloom thinning could fit into to a disease control schedule, especially if multiple products are eventually registered for bloom thinning. “That’s where I hope we can see it go with time.”

Putting all these pieces together into a precision thinning program will no doubt take some trial and error, but Schupp is excited that Mid-Atlantic growers can start exploring blossom thinning.

“We’ve been promoting the concept of the nibble approach. With multiple tools we can kind of finesse the crop load and this will open up the bloom time as well,” Schupp said. “We could apply up to 10 different thinners from bloom to 25 mm. I don’t think we will, but it’s good to have more options.” •

—by Kate Prengaman

Related:

—Pollen tube growth model makes thinning more precise

—Help for apple blossom thinning

Leave A Comment