Growers must consider a long list of factors when determining whether a block is profitable enough, and those factors only intensify as costs of production rise.

So, when do the economics just not pencil out any longer? And if that’s the case, and block removal is on the table, how does a grower decide what to do next?

A trio of longtime Washington growers shared their thoughts during a panel in February before Washington State University’s Next Generation Tree Fruit Network, an educational partnership launched in 2016 with WSU and the state’s young growers.

Dave Gleason of Domex Superfresh Growers, Jeff Cleveringa of Starr Ranch Growers, and Dale Goldy of Gold Crown Nursery and G2 Orchards shared insights on the factors influencing block removal, and internal and external threats to making a profit, as well as tools to aid in new variety replanting decisions.

(Note: Gleason delivered Cleveringa’s prepared presentation because he was unable to attend. Good Fruit Grower reached out to Cleveringa after the seminar to elaborate.)

When do you pull the plug?

“If we had a perfect world, our great-grandfathers would have planted an orchard that would still be producing fruit and pay the bills,” said Gleason, Domex horticulturist and proprietary variety developer. “But that is not always the case.”

The first task: math, or more specifically, enterprise budgeting.

If a grower has 100 acres in 10-acre blocks, each block should be considered an enterprise, with its own costs, he said. One block might be more susceptible to mildew and have higher spray costs, while another might be harder to thin or involve more ladder work, resulting in more risk and higher labor costs.

“You have to look specifically at what your costs are for each block,” he said.

Then, spread out farmwide costs across the entire operation. These could include irrigation, power, the costs associated with inspections (or programs to prevent inspections), food safety measures or, if companywide, an organics program. Growers with a business plan also must have money going to support ongoing development of the business.

“Many times, people might not realize their other blocks are supporting one block that isn’t making money,” he said. “You have to look at each of them as a separate entity.

”It’s a simple two-plus-two-equals-four analysis, but the homework involved to determine those exact costs is important. “You want a net income per acre, and you want to not just break even, but make a profit,” Gleason said.

Further, grower returns cycle from year to year, he said. “One year, we lose money, then make money for two,” he said. “You have to look at averages over time.”

Growers must always be ready to pull the plug, but that isn’t necessarily a one-year consideration, he said. Hail one year is one thing; hail three straight years could end an operation.

When it comes to replanting, growers must have the long vision to choose a path that will be profitable for 15 or, ideally, 20 years and suit every partner. “You’re partnering with not only your family or people in your company, but also who’s marketing the fruit, who’s packing the fruit,” he said.

And do your homework.

“Before you step into something new, go with your eyes wide open, understand your risks and do a good business analysis,” he said. “As a grower or manager, you know a lot about your location and its potential. You want to make sure any possibilities fit the reality.”

For example, recent early freezes could wipe out the potential for later varieties in some regions. And while WA 38, the variety marketed as Cosmic Crisp, was one of the most studied varieties growers have seen, growers are still learning more about it in the field, he said.

“There are details of everything. Basic horticulture gets you started, but you have to learn how to finesse that to get your target fruit, the yield and quality you need to be successful,” Gleason said.

Growers should have all that information before making a replanting plan, and the replanting plan should fit in with the overall business plan, which might call for cycling 5 percent of your acreage every year.

What do you plant?

Cleveringa, who heads research and development for Starr Ranch, recommends getting to know as much as possible about a variety before you plant:

—Does the variety produce a high quality and a high volume of fruit?

—Does it grow well in certain areas and only in certain areas?

—Are the returns still good for growers? “If it’s not profitable, then you better get out,” Cleveringa said.

—How many retailers are carrying the variety with some success?

—What is the marketing plan and volume necessary over time?

—What is the potential for both the domestic and export markets? (Because hitting both is always ideal.)

—Is there a royalty stream that makes sense?

—Who else is doing it?

At a minimum, growers must be nimble and quick to change, Gleason said. “In these new higher-density systems, you may be back into production in two years” when replanting, he said. “It gets you back in the game far quicker, but you still have to analyze the impacts for those years where there are costs but no income.”

And new varieties require volume, he said, which growers must build up quickly.

Retailers understand that the f.o.b. price must make sense for them, as well as for the grower, packer and marketer, Cleveringa said, but the days of $1,000 bin returns probably won’t come around for a very long time. That means setting realistic expectations.

“If your new variety is a high producer of quality fruit, then you don’t have to have the same f.o.b. structure as you do if it’s a lower-volume producer,” he said. “You have to adjust for 50 percent or 80 percent packout.”

Excitement must come from the marketing desk, Cleveringa said, because they are the ones who must convince retailers to take your product.

Overall, growers should set a realistic plan, gather information everywhere they can, execute and then adapt and be flexible as goals change — and if all else fails, be resourceful, Gleason said.

“You don’t want to be the leading edge, but you don’t want to be the last man standing either,” he said. “Do your homework, and when you make your decision, you have to risk enough to be able to have a good impact on your business.”

Cleveringa echoed Gleason, saying that while small growers must be quick to change and adapt to survive, it’s also one of their advantages. “Large, vertically integrated companies take a long time to turn big ships,” he said. “Big growers also have economy of scale to survive, so you have to be first to the next highest returns.”

Graphic: Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower)

Digging in

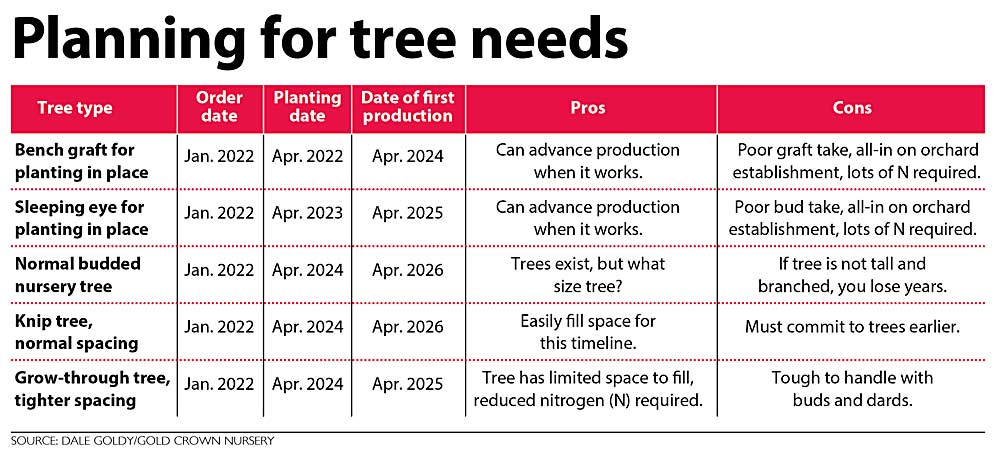

When an institutional investor is at the point of making a replanting investment, they want the orchard to be planted immediately by whatever means possible, said Goldy, an orchard and nursery owner. But growers need to understand the risks involved with the different paths for getting to marketable fruit that excites consumers.

Planting a bench graft or sleeping eye in place can advance production — when it works, he said. But it’s at least three years before a grower can risk leaving fruit to harvest — and the reality is growers probably shouldn’t leave fruit on some of those blocks in the third leaf. Plus, all it takes is a slightly poor graft take to end up with a mess.

“You’re building the trellis, you’re putting all the irrigation in, you’re fully committed to this thing Day 1, and if it doesn’t work, you have a significant problem in meeting your goals of production that are already embedded in your spreadsheet,” Goldy said.

A normal budded nursery tree has the same order date, with planting and production dates a year later than a sleeping eye. But if there’s a failure, it stays in the nursery. “I haven’t spent any money on trellis. You’re not committed to the full project like you are the other two,” he said.

A knip tree, started as a bench graft then kept in the nursery for the same length of time as a budded tree, results in a tree that is 4 feet with feathers. In the second year, the nursery cuts it off and grows a new top through the established root, which helps the nursery to get branches at the right heights, he said.

A lot of the Geneva rootstocks growers use today work well for this approach, Goldy said.

With a knip or grow-through tree, by making cuts high, there is less impact on root development, he said. “It can be enough that we’ve had people complain on the knip trees that they can’t get them through the tree planter very well,” he said. “That’s sort of the goal.”

Goldy draws a direct line between planting decisions and fruit quality for new varieties. Growers are still learning about the horticulture of a new variety at the same time the marketing department is trying to impress customers.

“Each time we started out with a new variety, we always hit the wall of getting the trees in balance and settled down and producing high-quality fruit,” he said. “Say the space isn’t filled yet. The problem with that is if I’m fertilizing to make sure I fill the space, I’m in conflict with the marketing department giving the consumer a piece of fruit to be impressed with. We need to get better with the horticulture to find the balance.”

And growers need to assume that they’re going to get better at horticulture over the next 15 to 20 years and factor that into the long-term decisions they make, such as trellis design.

Over the course of his career, Goldy said, he has seen that, as the velocity of change is increasing, growers don’t spend enough time talking about the time-value of money — and understanding the impact that has on horticulture.

“Within the industry, we have people who do horticulture and people who do spreadsheets,” he said. “Making sure the lines of communication are clear between those two groups is important.” •

—by Shannon Dininny

Leave A Comment