Apple growers know calcium helps avoid bitter pit. Anyone with Honeycrisp can tell you that. And many more know that too much potassium prevents the tree from taking up calcium.

But that doesn’t mean you can just skimp on potassium, either. It’s a key nutrient the plant relies on for photosynthesis, weathering stress and producing fruit.

“We don’t want to think that growers are too afraid of the bitter pit situation and then they stop applying potassium,” said Bernardita Sallato, a Washington State University tree fruit extension specialist with a background in soil science.

Striking the delicate balance between potassium and calcium has vexed growers for decades, and still does. Researchers admit they don’t have all the answers yet, though current projects may shed some light. Sallato and plant physiologists Lee Kalcsits of WSU and Lailiang Cheng of Cornell University all have research projects underway to tackle these complex nutrient interactions.

In Washington, Kalcsits and Sallato have teamed up to test how different rates of nitrogen, potassium and magnesium affect fruit quality, disorders, return bloom and tree vigor in mature Honeycrisp and WA 38, the apple marketed as Cosmic Crisp. Their work is funded by the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission.

“Frankly, we don’t have answers to many of the questions …,” said Kalcsits, a tree fruit physiologist at WSU. “We expect to start to gain a clearer picture over the next three years as our experiments progress.”

Meanwhile, Cheng and Kalcsits are currently involved in a five-year U.S. Department of Agriculture Specialty Crop Research Initiative project that focuses on apple rootstocks but features a component about how nutrient balance affects bitter pit in Honeycrisp apples. The grant is scheduled to end in August 2021 but Cheng already has some results. He is planning a series of workshops in the spring of 2021 to share them. The New York State Apple Research and Development Program and the Michigan Apple Committee also support Cheng’s ongoing work balancing calcium with potassium.

Basic science

Though questions still remain, growers should know a few scientific basics about potassium, Sallato said. She gave a primer at the Washington State Tree Fruit Association Annual Meeting in December in Wenatchee.

A potassium deficiency can cause a host of problems, reducing fruit size, color, firmness and soluble solids. It also can lower yields, stunt growth and leave the tree more susceptible to all forms of stress. The effects of potassium excess are harder to measure than deficiencies. It will not cause symptoms of toxicity or kill cells as will boron, manganese, sodium or even nitrogen.

In her surveys of Washington soils, 42 percent of sites were too high in potassium, 32 percent were within a healthy range and 27 percent were deficient. Generally speaking, the sandy Columbia Basin soils had less potassium, and less variability in levels, than the loamier Yakima Valley locations.

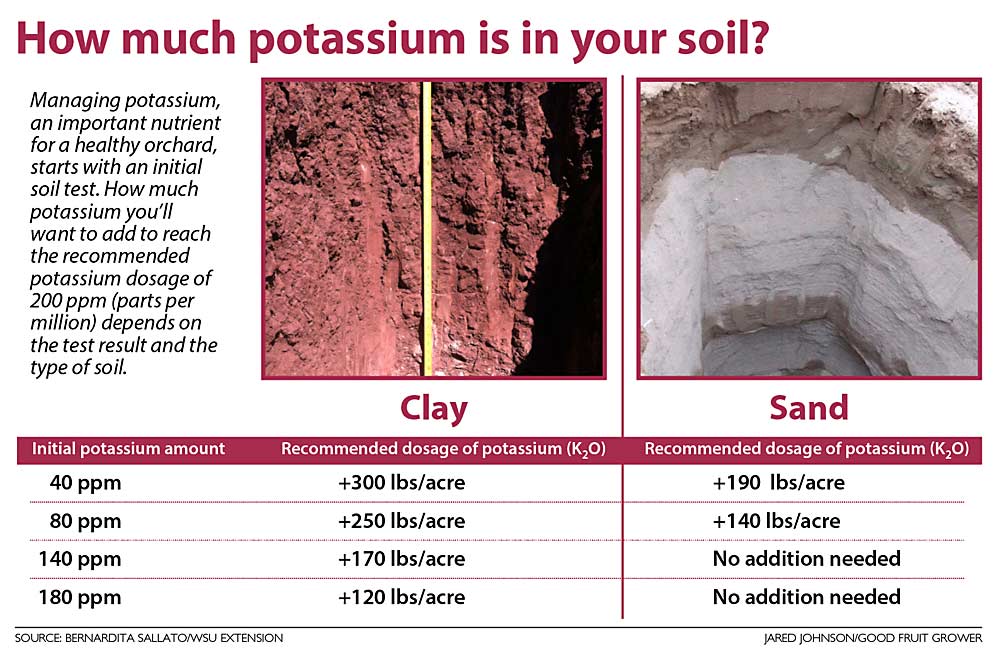

Getting the right amount depends on soil type and irrigation, Sallato said. Sandy soils usually have no charge, so most potassium added by growers, either through fertilizer, mulch or compost, is available for the plant to take up. They don’t need to apply a lot but probably will have to apply it often because of leaching.

Clay, on the other hand, absorbs potassium into its layers. Growers could spend years supplementing potassium-deficient clay soils. They will need to apply more overall but less often, maybe once per year or even once every three years.

The most important thing is to make sure the plant has an adequate level of extractable potassium. Labs will provide this in parts per million or milligrams per kilogram; a good target range is 150–200. “That’s the number they should use to make their decisions,” Sallato said.

The rest of the battle

However, with potassium, soil is only part of the battle. Many factors — rootstocks, soil type, irrigation levels and variety — affect how the plant transports nutrients to leaves and fruit. That’s why, in Washington, Sallato doesn’t recommend input ratios, even though growers often ask her for one.

Sallato suggests foliar analyses to test for potassium uptake levels. If it’s low in the leaves but high in the soil, something is wrong with the uptake in the roots.

Cheng at Cornell has guidelines for leaf analysis, but apple peels also work. His studies show that Honeycrisp apple skins had half the calcium and 50 percent more potassium than skins of Gala, considered at relatively low risk for bitter pit. Cheng is developing a peel sap analysis for Honeycrisp that may allow growers to get the results back in a few days after sampling midseason, in time for them to adjust their management practices.

The three researchers and others have a lot of recommendations and tools, but they are still fine-tuning them. They have made good progress, Cheng said. “But there’s still a lot to learn.” •

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment