To embrace an integrated pest management approach to pear psylla management, growers needed to have faith that natural enemies would show up in the orchard at the right time and magnitude to protect the crop.

Now, they can trust but verify.

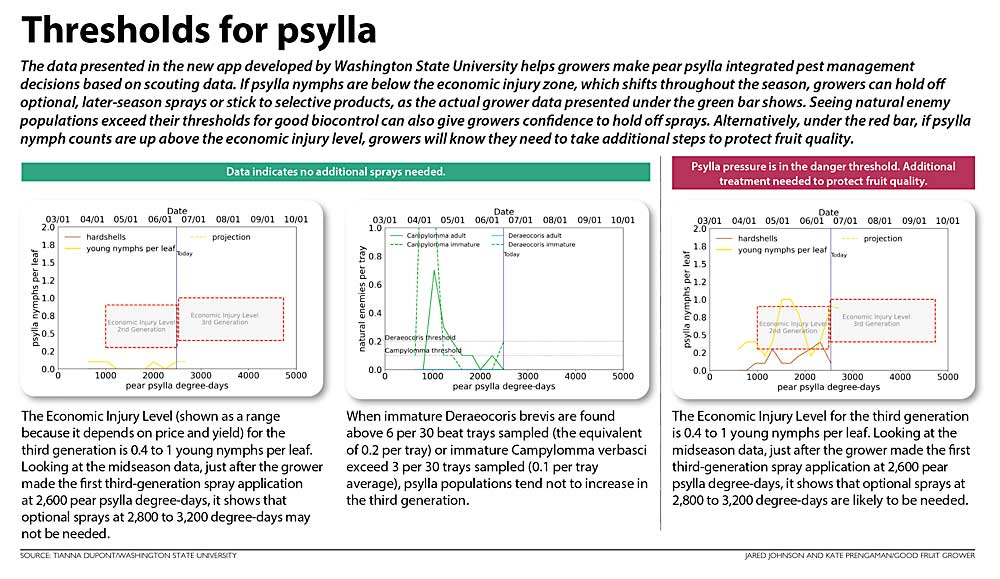

Development of natural enemy thresholds and a new areawide scouting approach led by Washington State University makes it easier for growers to feel confident in their psylla controls — or know when it’s time to apply a selective insecticide instead.

“The second generation is where the tough decisions are made about if the predators can catch back up or not. You want to start softer to get them a chance,” said Neil Johnson, a pest consultant with Chamberlin Agriculture.

Having the data from the new scouting network helped him understand when and where the natural enemy populations were mounting, he said during a panel discussion at North Central Washington Pear Day in January.

That’s the goal of the pilot scouting network program, said Tianna DuPont, WSU Tree Fruit Extension specialist. It pairs with research she and her colleagues have done to measure the economic thresholds for psylla pressure and natural enemy activity to guide growers’ decisions.

The term “integrated pest management” refers to using cultural, biological and insecticidal controls, informed by monitoring and thresholds. Until now, those thresholds have been a missing piece that would help growers use biological controls, she said.

“When we’re talking about an integrated pest management toolbox for pears, we’re talking about not only the summer pruning and honeydew washing that you guys are familiar with, but wanting to make sure we’re adding that biological control to the toolbox,” she said. “Remember our earwigs and campylomma and deraeocoris, those natural enemies, we’re only going to have (them) in the toolbox if we’re using selective insecticides.”

Thresholds

For years, growers have been asking what ratio of natural enemies to psylla they need to ensure strong biological control.

To answer that question, researchers started by defining the line at which psylla pressure leads to economic injury — in other words, where the cost of additional control treatments is worth it relative to the value of the fruit protected by these sprays.

And it’s a balancing act.

“When we have injury, it’s too late,” DuPont said. “We want to be thinking about next week.”

Using data from over 80 season-long data collections over multiple years in commercial orchards in the Wenatchee River Valley, along with a handful in Medford, Oregon, researchers identified the percentage of Anjou fruit downgraded to Fancy or culled due to psylla damage and compared that to the number of psylla nymphs found per leaf. Using that data to build a psylla population model allows researchers to predict if the number of nymphs present today will result in economic injury for the following week.

Using $30-per-box pricing for U.S. No. 1s with a yield of 40 bins per acre, having an average of less than 0.4 psylla nymphs per leaf in the third generation means growers should be safe to hold off optional sprays, DuPont said.

Pest consultants already routinely track psylla numbers, but for the first time, researchers tracked natural enemy populations to develop similar inaction thresholds.

“What we found was six deraeocoris immatures per 30 beat trays or three campylomma immatures per 30 beat trays was the level that was keeping that population flat,” she said.

During the talk, she shared several examples of scouting data relative to these thresholds, which growers relied on to feel confident skipping a late-season spray or to know they needed to spray to protect fruit quality. One example showed a block with psylla nymphs hovering around 0.2 per leaf and immature deraeocoris numbers that, while fluctuating, still stayed well above the threshold of 0.2 per beat tray (or six per 30 trays).

“In this last block, they didn’t actually reduce the number of spray applications, but they felt confident to stay in their integrated pest management program (using selective products) because, again, they were watching their psylla numbers stay nice and low and their natural enemy numbers, in this case deraeocoris, were up above that inaction threshold,” she said.

That’s very important data. The downside: It’s a lot of work to gather the scouting data and do this analysis.

Scouting network

A grant from the Washington State Department of Agriculture supported the development of a pilot project for scouting in grower orchards across the Wenatchee River Valley and an app WSU designed to help participating growers understand the data.

In 2023, the first year of the project, DuPont and Ricardo Lima Pinto, also with WSU, worked with participating growers to scout in their orchards on a weekly basis and to build and refine the app to share the data. This season, they will train additional scouts to join the project, with the vision that it becomes industry-sustaining.

“The pilot project is helping us to form partnerships with growers, consultants and packing houses to form a network of scouts, which will provide additional natural enemy and pest data that growers can compare to thresholds for their farms,” DuPont said.

Growers and pest consultants who participated in the first year shared their experiences during the conference.

Kevin Carney, a Cashmere-area grower, said that at first, he was skeptical about the IPM approach and confused about how to interpret the data. But Lima Pinto and DuPont worked with him to understand what the beneficial numbers meant in terms of psylla control.

“I’m a cherry grower, too, so usually you load up your pear blocks in June and then hope you get through cherry season. I really wanted to spray Bexar before I went to pick cherries, but we looked at the beneficials and made the decision to slow my roll and see what happens,” he said. “The scouting data made it easier for me to be patient with the IPM.”

Johnson, the pest consultant, said the data should really help growers jumping into the IPM approach, because it is a different way of farming.

“I would say, don’t bite off more than you can chew. If there is an IPM or organic block next to you, that’s a good place to start,” he said. “To be successful, we need to work together to build an areawide approach.”

Grower Dave Burnett said he was inspired to transition to the IPM approach based on the success his friend, Mel Weythman, had in the previous year. (See “Integrating IPM in pear orchards.”)

“I believe we have to do this because the conventional way was not working,” Burnett said. Yes, there was a learning curve to using the data, but as he switched from conventional sprays to selective products, the natural enemies came out in force.

Several speakers mentioned that 2023 was a relatively low-pressure year for psylla in general, so they are cautiously optimistic. But Burnett, fully optimistic, believes that could in part be due to the embrace of IPM approaches, which has encouraged beneficials across the valley.

In his own orchards, the change in one season amazed him.

“I really didn’t think you can change something in one year, but with the data we had, I’ll never go back to conventional,” he said. “Every time you spray something in your orchard, you change something that’s going on out there. For positive or negative. I think we’re just starting to learn how we use this data.”

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment