The Swindeman family was often told they were crazy for growing apples in Deerfield, Michigan, a rural community south of Detroit. And for buying frost fans. And for regularly irrigating their trees. But year after year, they produced consistent crops — even in the disastrous year of 2012 when Michigan lost nearly all of its apples.

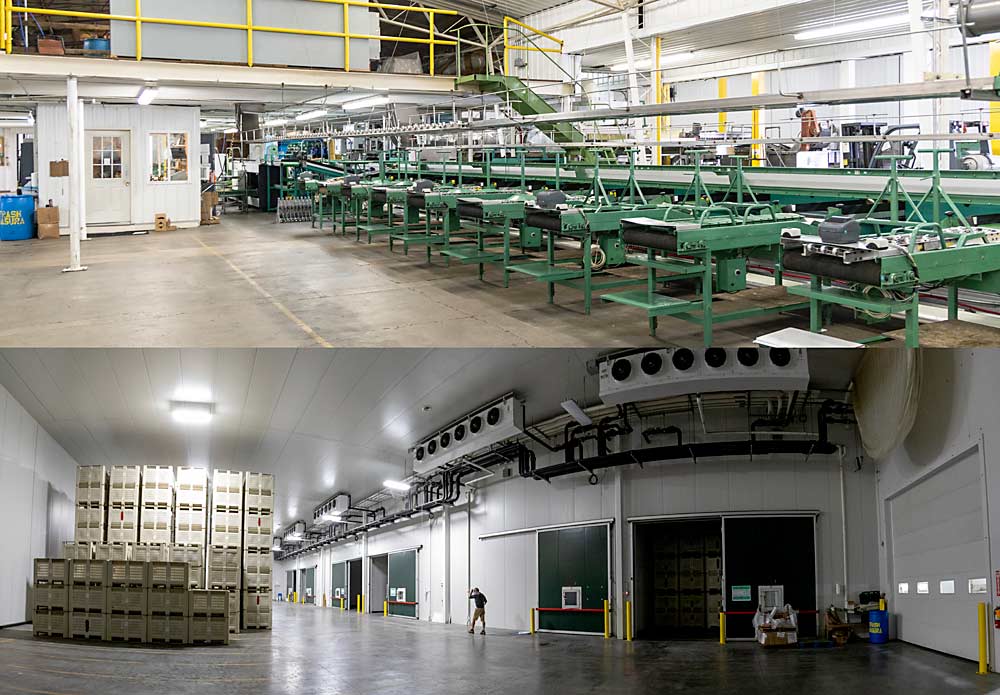

The family farm that began when Walter Swindeman planted two dozen acres of apple trees in 1935 has grown into one of the largest packing and sales operations in Michigan — despite the fact it’s nowhere near the state apple industry’s center of gravity.

Crazy? Like a fox.

Investments in risk management, such as those frost fans and drip lines, helped the family succeed without the climate advantages enjoyed by most of Michigan’s wholesale apple orchards, which stretch along the western side of the state’s Lower Peninsula. There, modest elevations and warm air rising from Lake Michigan provide some protection from frosts and freezes. Most of the largest apple orchards and packing houses are clustered on what’s known as the Fruit Ridge, north of Grand Rapids.

But Deerfield, located on flat land in Southeast Michigan, was never considered an ideal place to grow apples on a large scale. There are orchards in the region, but most are small, direct-market retailers serving the Detroit metro area.

The Swindemans are an exception — in more ways than one, said Bob Tritten, who worked with three generations of the family as Michigan State University Extension’s district fruit educator before retiring in 2021.

Applewood Orchards, the Swindeman farm, was “by far” the largest commercial operation Tritten worked with in his 42 years covering eastern Michigan, he said. He boiled their success down to three things: investing in high-density orchards, training and pruning those new orchards to make them productive within three years, and investing in wind machines to help prevent frost and freeze injury.

“They’re one of the leading growers in Michigan,” Tritten said. “When they start a new block, they do everything right, from the trellis system to planting to irrigating immediately after.”

The Swindemans have always been innovative, always looking for new ideas from other fruit regions. They were early adopters of H-2A labor, wind machines, drip irrigation, hail netting and reflective fabric, Tritten said.

Applewood Orchards

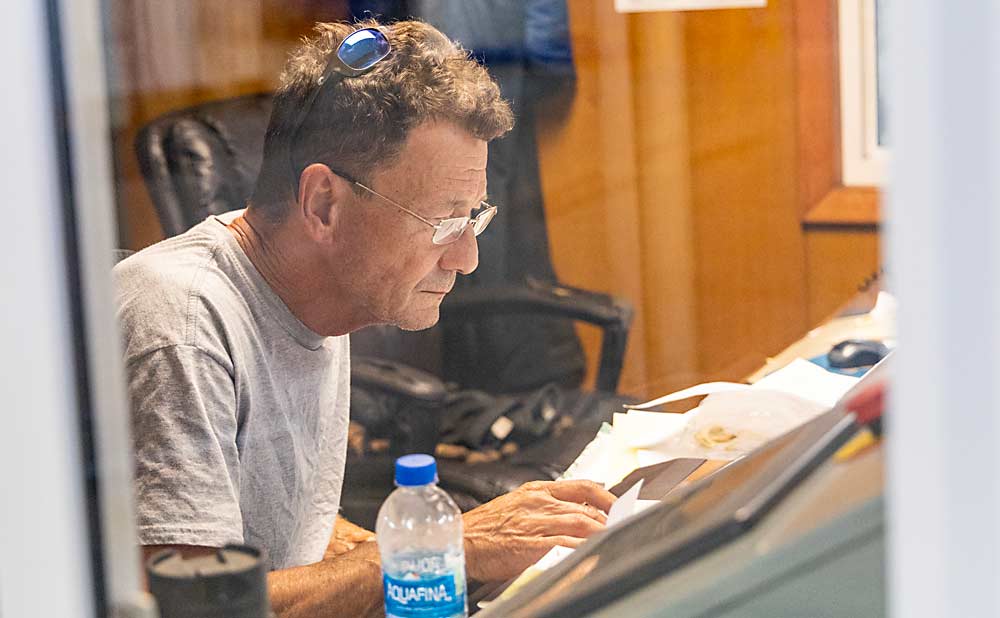

The farm is currently led by three Swindeman brothers, all in their 60s. Steve runs the packing house in Deerfield. Scott runs the sales arm, Applewood Fresh Growers. Jim runs the orchards.

The brothers installed their first wind machines, or frost fans, more than 15 years ago. Flat land gave them an advantage there.

“We typically get a better inversion than any other spot in Michigan,” Jim said.

The fans proved their worth in 2012, when an early spring was followed by savage freeze events that destroyed nearly all of Michigan’s apple crop. Most growers were lucky if they had any fruit at all. The Swindemans had a full crop.

After 2012, more frost fans started going up above Michigan orchards. Applewood Orchards now has 32, Jim said.

The family has been consistently watering their trees for decades. At first it was overhead irrigation, but now water is provided via drip.

“We started irrigating when people were saying you didn’t need to irrigate apples in Michigan,” Steve said. “This was during the transition to dwarfing rootstocks, which need a steady diet of moisture. We always felt it was great for consistency. Now, you don’t see too many blocks in Michigan that aren’t irrigated.”

These days, the Swindemans grow more than 360 acres of apples in the Deerfield area, islands of straight-rowed trees surrounded by vegetable fields and woodlots. The soil is mostly sandy loam, with spots of clay loam, Jim said.

They grow varieties including Gala, Honeycrisp, Fuji, McIntosh, Ambrosia and MAIA1 (marketed as EverCrisp), as well as managed varieties Minneiska (marketed as SweeTango), Nicoter (Kanzi) and MN55 (Rave), said Michael Swindeman, Scott’s son.

They do a lot of work preparing new blocks. Irrigation is installed first, so trees can be watered down the day they’re planted. Their trellises have six wires, with the top wire reserved for hail nets. To manage the canopy, they remove large limbs and simplify the remaining limbs.

“I still say the best system is the simplest system, so you can get the work done the way it’s supposed to be done,” Jim said.

They still mostly pick with ladders but are gradually shifting to platform picking. They use two mobile platforms for harvest, pruning, trimming and thinning, and they plan to add a third.

Michael said the region’s biggest growing challenges are high summer temperatures and humidity. Jim added they don’t get as much snow as western Michigan, so their trees aren’t as insulated during cold snaps.

Scott said that other than a couple of hailstorms, Mother Nature has treated them well. And their orchards do get a bit of a cooling effect from Lake Erie, a little less than 20 miles to the east.

Planting seeds

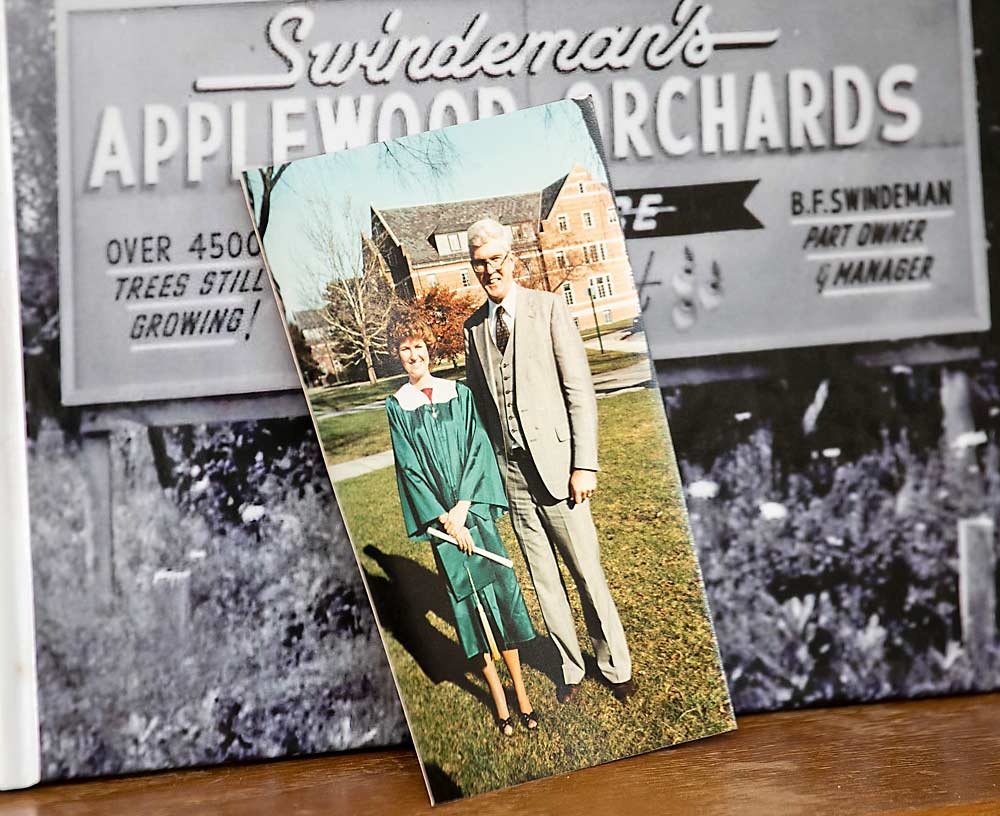

Walter Swindeman, a wholesale grocery salesman in Southeast Michigan and Northwest Ohio, planted the family’s first apple trees in Deerfield so he could sell apples to local stores. The home farm and packing plant sit on the original 24 acres Walter bought from his father-in-law in the 1930s.

“Thank God nobody told him that you can’t grow apples in Southeast Michigan on flat grounds,” his grandson, Scott, said.

Scott’s parents, Bernard and Beverly Swindeman, took over when Walter and his wife, Lucile, retired from farming. Bernard was always interested in trying new things and learning from growers in other regions. He built one of the first controlled-atmosphere storage rooms in Michigan in 1958.

“Every time Dad went out to Washington, it was expensive,” Scott said. “He’d come back and say, ‘We’re going to do this ….’”

Scott and his brothers started taking on more responsibilities in the 1970s. Bernard mostly retired from farming in 2002. He died in 2016. Beverly, 86, still splits her time between Michigan and Florida.

In the 1980s and early ’90s, the Swindemans packed fruit for some “phenomenal” growers in Ontario, Canada. That supply eventually dried up, due to changing exchange rates and cross-border regulations, but the experience was “instructive, because the quality was a big step above what was being grown in Michigan at the time,” Scott said.

Seeking to expand and strengthen their position in the marketplace, the Swindemans eventually branched out into western Michigan. They’re one of the partners running the Elite Apple packing facility in Sparta. Scott, who’s lived in western Michigan for the past decade, runs the sales desk from there, which has been called Applewood Fresh Growers since 2019.

Between the Deerfield and Sparta packing houses, plus another packer farther north, Applewood Fresh Growers ships about 1.5 million bushels a year for dozens of growers. It’s now one of the three largest apple marketers in Michigan, Scott said.

They bought an orchard in West-central Michigan, north of the Fruit Ridge, a few years ago, where they recently planted about 60 acres of apples, mostly Honeycrisp and Rave. The cooler climate and sandier soils up there should produce a redder, firmer piece of fruit than what they can grow in Deerfield. But they’re still getting used to the hillier land up there, Scott said with a grin.

Steve, Scott and Jim are currently pondering the future of the family business and the best way to hand it off to the next generation — Scott’s son, Michael, and Jim’s sons, Brandt and Trent. Growing apples has never been easy, but Scott predicted that certain aspects of the business, like labor and regulations, are only going to become harder.

“If you’re going to make things work in a family business, everybody’s got to understand each other’s responsibilities and duties,” he said. “It’s going to be up to those three to keep it going.”

—by Matt Milkovich

Apples run in the family

There’s a fourth Swindeman sibling, sister to Steve, Scott and Jim, who’s no longer involved in the family business but is still a part of the apple world.

Anne Swindeman grew up on the family orchard in Deerfield, Michigan. Like her brothers, she had a lot of different jobs, but her future career might have been sparked when her father, Bernard, handed her an ethylene analyzer when she was a teenager.

“Some kids get cars, I got an ethylene analyzer,” she said.

Bernard Swindeman worked closely with Michigan State University scientists, including postharvest researcher David Dilley. Anne joined Dilley’s postharvest lab during her second year at MSU, where she earned a master’s degree in horticulture, specializing in postharvest physiology.

Anne moved to Prosser, Washington, in 1985, where she coordinated Washington State University’s sweet cherry research program for five years. She then moved to Yakima, where she procured and inspected fruit for the short-lived Western sales arm of the Swindeman family business.

In 1994, Anne started a consulting business called Apple Advice. She’s still running it today, consulting on harvest timing, color enhancement, storability and other topics — “anything to do with fruit quality at harvest and beyond,” she said.

—M. Milkovich

Leave A Comment