With ever-increasing competition and dismal frozen and processing prices, this is not a good time to have or to start a blueberry farm in Michigan.

That was the message from Michigan State University small fruit educator Mark Longstroth, who gave a talk he titled “Can You Afford to Grow Blueberries? Drowning in the Blue Wave” at the Great Lakes Fruit, Vegetable, and Farm Market EXPO in Grand Rapids, Michigan, in December.

“I’m looking at some data here that are just depressing,” he said as he prepared his EXPO talk in late November. Especially hard hit are those growers whose business model is to cut costs by investing as little as possible in pruning, fertilizing or pesticide-spraying, so they can subsequently make a profit from the frozen/processing market.

That business model may have worked for decades, but it doesn’t anymore, Longstroth said. Farms that were once bringing in $0.65 to $1.50 a pound on the frozen market are making just 35 cents a pound in 2016, he said. With costs running from about $1,400 to $2,600 an acre to grow blueberries and an additional 25 cents a pound for machine-picking, the balance sheet tips into the red.

Fresh-market and organic blueberry growers aren’t faring much better. “Without the frozen price to support the fresh price, generally people try to move as much as they can into fresh, so the fresh price is being hurt, too,” he said. “Unless you’re an established blueberry farm and you’re spending a lot of money to get good yields and you’ve got a good marketing chain, you’re probably losing money growing blueberries.”

What happened?

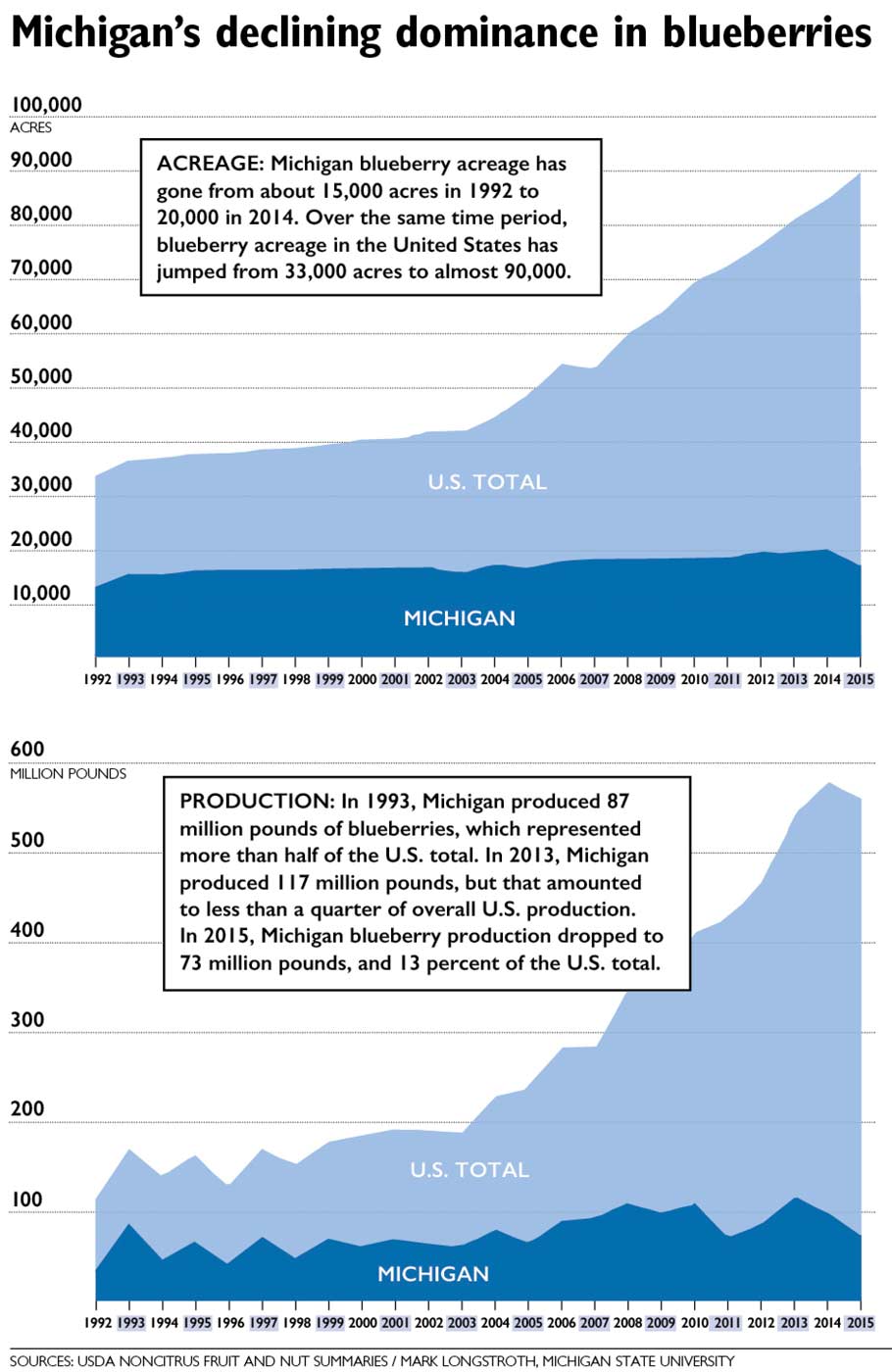

Several things are contributing to the price collapse for Michigan blueberries. The first is simple supply versus demand. In this case, it can be traced in large part to the publicity around the health benefits of blueberries in the 1990s, Longstroth said. “Suddenly people were planting blueberries all over the United States and all over the world,” he said.

Southeastern and northwestern states greatly expanded plantings, while major production regions formed in South America and British Columbia, and both began exporting to the United States.

In addition, Eastern Europe and Africa also started growing blueberries to export into Western Europe. “We’ve reached the point, I think, where the market is saturated,” he noted.

At the same time, new fields are more productive than older fields, and many fields in Michigan date back to the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s. “It’s pretty similar to what has happened in the apple industry several times in the past. You’ve got an oversupply of blueberries, and the older or less profitable blocks are at a point where they need to be removed and reworked,” he said.

Without profit margins, though, the expense to do that is difficult to justify, especially since the time from planting to full production in Michigan runs about 12 years.

A third issue is harvest timing. In the United States, Florida gets its berries to the fresh market earliest in the season and receives a premium price because of it. When Georgia enters the market a few weeks later, the added berries drop the overall price. The same thing happens again and again as the season progresses.

Fresh prices are low by the time Michigan starts picking, but start to rebound as other states finish their seasons. “It used to be that the most profitable fields in Michigan were those that picked last.

Today, however, those late-season crops are the ones that are most susceptible to spotted wing drosophila (SWD), which is really abundant by that time of year,” he said, noting that weekly sprays are necessary to keep the flies at bay. To make matters even more challenging, that late-season window for Michigan growers is cut short because South American blueberries start to arrive at U.S. fresh markets in late October.

SWD is an even bigger issue for Michigan organic growers, because they have few choices to combat the fruit flies. They are also competing with huge plantings that are going in the ground in eastern Washington areas that were formerly Red Delicious apple orchards, Longstroth said.

“The eastern Washington growers are getting very high yields primarily due to climate, plus that area is not a very good place for SWD to live, nor are there other blueberry pests, so they are organic almost by default.”

Rising from the (b)ashes

While the news is dreary, some Michigan growers can still have successful blueberry crops.

“This is the thing: It’s not how cheaply you can produce an acre of blueberries, it’s how many blueberries you can produce on an acre. In other words, don’t look at how much it costs you per acre to grow blueberries, but instead look at how much it costs you per pound,” he said. “The growers who double their input costs and triple their production are going to still make money as long as they have a market for their fruit. And for blueberries or for any fruit, if you don’t have a market for it, you probably shouldn’t be planting it.”

He hopes that the market oversupply will work its way out of the system in the next decade or so, and when that finally happens, Michigan blueberry farming will have to adapt to the times.

“Those 50 percent of Michigan growers who are relatively small and have a business model of machine harvesting for the frozen market are going to have to do some thinking, because what has worked in the past is not necessarily going to work in the future,” he said. “It’s distressing and I wish I had better news, but these growers are telling me they’re losing money, and I believe them.” •

-by Leslie Mertz

Leave A Comment