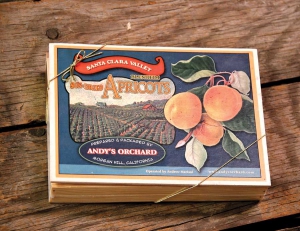

Andy Mariani holds a box of apricots and peaches at his Morgan Hill, California, orchard. (Courtesy David Karp)

In the early 1960s, Andy Mariani’s father grew apricots and prunes in California’s Santa Clara Valley, some for canneries, but mostly for drying. Fifty years later, Mariani is still following his father’s “old-fashioned” ways of picking tree-ripened fruit with high sugar, only now it’s called artisanal fruit.

When his father dried fruit, there was incentive to grow very sweet, tree-ripened fruit, said Mariani, explaining that sugar affects the drying ratio. “The more sugar, the more weight and yield you have in your dried fruit,” said the 70-year-old owner of Andy’s Orchard in Morgan Hill, California.

“That’s basically what we’re doing now—we didn’t lose that perspective of growing tree-ripened, flavorful fruit,” he said. “We evolved from growing it for drying to developing a niche market of diverse varieties and relying on the quality of the fruit to sell itself.”

Andy’s Orchard is located 15 miles from the San Jose-Santa Clara Valley metropolis, one of the ten most populated in the nation. His location gives him access to more than a million potential customers, but it also influences what he does and how.

Mariani is from a large winemaking and fishing family from the Adriatic Islands in the sea separating Italy from the Balkan peninsula. His father came to America in 1931 and, by 1935, had saved enough to purchase a small apricot orchard in Cupertino and bring his wife and family to America.

The homestead place (which now is across the street from Apple headquarters) was sold in 1957 and the farm relocated about 30 miles south to Morgan Hill. Mariani split off from farming the family orchards with his brother in 2003 to farm separately.

Urban fringe

Because he’s growing fruit on the urban fringe, he doesn’t have extensive acreage like those in California’s San Joaquin Valley. With less than 60 acres, he has to maximize profit on a small amount of land. “The way I’ve done that is by specializing and capitalizing on the consumer’s growing interest in highly flavorful fruit,” he said.

When Mariani talks about his fruit and growing location in the Santa Clara Valley, his wine roots are apparent. He uses terms like terroir (the French word to describe the effect of the environment on the fruit), cooling marine influence, and complexity to describe his fruit.

“Just like Napa and Sonoma produce higher quality red wines than those grown in the Central Valley, the same is true of stone fruit grown here,” he said. The cool nights allow trees to respire and fruit can stay on the tree longer, retain sugar and acidity, and develop rich, complex flavors.

He’s obsessed with flavor. His extensive variety mix of more than 150 selections has been carefully chosen with the consumer in mind.

“In the olden days, you grew what grows well in your area and then tried to sell it,” said Mariani. “Nowadays, you go to the market and work backwards. You have to know your market first, know what people want, and then try to grow it.”

That’s why he began growing greengage plums, a small European plum with chartreuse green skin and dull, green-colored flesh. Greengages are some of the most popular plums in Europe, he says, but few grow the variety in the United States. David Karp, pomologist and writer, partners with him in the greengage plums.

Sweet-sour cherries

Mariani, always on the lookout for specialty and unusual fruit, recently planted a small block of what he calls sweet-sour cherries. “I never thought I would grow sour cherries, but I had a couple of tart cherry trees and found that people went crazy for the fruit,” he said, adding that consumers didn’t balk at the $10 per pound price.

Some of the varieties are sweet enough to be eaten out of hand, while the more tart varieties are bought for home processing. Few growers in California produce tart cherries, so the fruit is something of a novelty. Mariani plans to bring sweet-sour cherries to the Santa Monica Farmers’ Market—where restaurant chefs do their shopping—when his young trees come into production.

He worked with Michigan State University cherry breeder Dr. Amy Iezzoni to identify and source tart and sweet-sour cherries for the one-acre plot. Varieties planted include Balaton, Danube, Jubileum, Montmorency, Belle Magnifique (an old Duke variety), and the German variety Schatten Morelle.

Direct sales

Andy Mariani dries and packs his own apricots and sells them through his farm store and on-line sales. (Melissa Hansen/Good Fruit Grower)

With the exception of cherries, he packs his own fruit and markets it through direct sales. He also dries some fruit for dried fruit sales. He markets his fruit through three main channels: wholesale, retail (through the on-farm store and selected farmers’ markets), and a four- or eight-week subscription program that sends overnight shipments of tree-ripened fruit to the doorsteps of consumers.

Last summer was the first that Andy’s Orchard secured a coveted vendor spot at the Wednesday Santa Monica Farmers’ Market in southern California. Ken Brown, his nephew and general manager, is in charge of the Santa Monica market.

In the summer, Andy’s Orchard employs about a dozen people. It takes about five to run the retail store managed by Lisa Silva. Brown works with the production crew of six full-time employees who pick fruit in the morning and pack it in the afternoon for the store or outside sales. Contract labor is used for cherry harvest.

Mariani considers his cherries more like a commodity than his other fruit. “Cherries pay the bills and allow us to do things that aren’t always the most efficient, like grow tree-ripened fruit,” he said. He packs some cherries for sale in the farm store and direct shipments, but most of the crop is sent to Felix Costa and Sons, a Lodi, California, cherry packer.

Challenges

Growing fruit in a rapidly urbanizing area is his number-one challenge. With homes on the backside of the orchard and a school across the street, orchard sprays must be carefully timed. Pilferage of fruit and illegal dumping in the orchard are also problems.

Spotted wing drosophila has become his biggest pest problem. Until it appeared in the late 2000s, he farmed almost organically. He’s found the pest doesn’t seem to bother apricots and peaches much, but prefers smooth-skinned fruit like nectarines, plums, and cherries. He no longer traps for the insect but just assumes it is present and sprays every seven to ten days.

It’s also challenging to grow labor-intensive artisanal fruit. His tree-ripened fruit are picked six times, a practice he calls highly inefficient, compared to two or three for what he calls commodity stone fruit. Yield and packouts are lower, and picking is slow because ripe fruit must be picked gently and placed in foam-lined lugs with only two layers in a box.

Mariani’s focus on flavor and his unique approach to marketing has been successful, but uncertainty clouds the farm’s future. Residential housing is closing in, and he has no children interested in taking over. There’s a possibility that his nephew will continue the business, though it will likely need to be relocated.

But for now, Mariani has found success in his market niche of customers who want tree-ripened, highly flavorful fruit. •

—————

Unique varieties

Greengage plums, originally from France, were imported into England in 1724 by Sir William Gage. Colonists first the first to grow them in the United States, and they were also grown in the plantations of American presidents George Washington and Thomas Jefferson. Andy Mariani is one of few U.S. growers who grow the green plums commercially. These are the Cambridge Greengage variety. (Courtesy David Karp)

Andy Mariani of Andy’s Orchard has a variety list as long as some nurseries. He grows about 150 varieties of cherries, peaches, nectarines, plums, and pluots to sell through his on-farm store and selected markets.

But he has another collection of some 300 varieties of stone fruit, which may be one of the largest private collections in the country. The collection includes heirloom and specialty varieties, some used for research and development, and some kept just for the sake of diversity.

He’s also bred and developed several of his own varieties specifically adapted for his climate, such as his Kit Donnell peach.

“My signature fruit is the Baby Crawford, a peach that’s small but with juicy, melting texture that consumers go crazy over,” he said. Baby Crawford, a variety from the breeding program at University of California, Davis, was rejected because it had poor color and was too small for commercial growers.

“I grow a lot of Baby Crawford,” said Mariani. “Customers love it, and I can’t keep it on the shelves.” The Kit Donnell is an offspring of Baby Crawford. With a later harvest date than its parents, Kit Donnell helps extend his market window.

Mariani develops his new varieties through a local hybridizing group that includes local fruit society members, Master Gardeners, and members of California Rare Fruit Growers, an association of fruit-growing enthusiasts. Volunteers help with breeding and making crosses, planting seedlings, pruning trees in the trial, and evaluating fruit. The Rare Fruit group helps fund the breeding work and maintain the small experimental plot.

“Flavor is our only criteria when evaluating,” he said, noting that it takes about eight years to finalize a new variety.

Last year, the group crossed Silver Logan, the best white peach in Andy’s Orchard, with several different nectarine selections. Out of 50 to 60 seedlings from the crosses, they should find one that will expand the season on either side of Silver Logan, he says. The group also is working to develop red-fleshed nectarines.

Some of the older or unusual stone fruit varieties grown at Andy’s Orchard include:

Alameda Hemskirke apricot

Blenheim apricot

Black Tartarian cherry

Black Republican cherry

Panamint nectarine

White Rose nectarine

Dixon peach

Elberta peach

Pallas peach

Gold Dust peach

Elephant Heart plum

Inca plum

Padre plum

Greengage plum

Mirabelle plum

Leave A Comment