Walking through a packing line with a food safety expert can feel a bit like opening your eyes to a whole new world, one where risks lurk in hard-to-clean corners, hide in driers and float down flumes.

Walking through Borton Fruit’s new Yakima, Washington, packing house with food safety and compliance director Jeremy Leavitt, on the other hand, is to see solutions both cutting-edge innovative and staggeringly simple.

The 550,000-square-foot plant is expected to start operations this fall, packing 150 to 180 bins an hour, Leavitt said, and it’s packed with efficiencies that will significantly cut the company’s energy, chemical, water and labor costs.

Investing in food safety reduces the risk of a contamination event, but it also makes economic sense, Leavitt said. Borton estimates that using ozone for sanitation will cut chemical use 25 percent, radiant heating will save 15 percent on energy bills and a centralized chemical delivery system will cut the sanitation program’s cost by 35 percent.

“I have had 100 percent buy-in on everything from the design of the belts to all the chemicals, the bin sanitation system,” Leavitt said. “It’s really been neat working for a company that sees the value in building it right from the beginning.”

From the ground up

The vision for the new facility came from co-owner John Borton and chief engineer Malcolm Hanks, said Eric Borton, director of business development.

“Their blood, sweat and tears has really gone into the facility,” Eric Borton said. “We look at this plant as a platform for our family and company to grow into the future. We wanted to build a world-class plant and facility that was set up to be as cleanable as possible, for whatever comes our way, and set us up for success and efficiency.”

With Hanks’ office right next door, Leavitt was able to work hand-in-hand with the engineers and owners to bring a food-safety-first mindset to the facility, starting with its literal foundation.

“Initially, everything started with the sloping of the floors, the designs of the drains, which are sort of U-shaped. There’s no corners so it is easier to clean,” Leavitt said. Only food safety experts get excited about the design of drains.

Everything is plumbed under those floors as well: radiant heat and cooling, which means no blowing air or dust; hot water at just the right temperature; aqueous ozone and premixed chemicals for cleaning and sanitation delivered directly to eight hose systems stationed around the facility.

The centralized chemical delivery system is one of the first of its kind in tree fruit packing, Leavitt said.

“I can say I want to use 2 ppm of chlorine foam and I can send that out to eight different stations in the plant,” he said. Not mixing by hand reduces the risk of mistakes, spills and exposure to workers, plus it should make sanitation crews much more efficient.

Then, all the data from that automated chemical delivery is tracked and stored for analysis.

“I know how long each station was used, what concentration was used, and I literally have a spreadsheet I can show to an auditor of exactly what we do,” Leavitt said. “I can be sitting in my house monitoring my sanitation crew.”

That’s a huge advantage, since sanitation crews typically have high turnover in a difficult job, performed during the night shift, said Jacqui Gordon, education director for the Washington State Tree Fruit Association. Making that oft-invisible work accountable: “That’s the dream for everyone,” she said.

The Birko by Lagafors system can pay for itself in a year to 18 months, in terms of chemical and water savings, said Bob Ogren, Birko vice president of equipment. The technology was developed in Europe, where higher water, chemical and labor costs have pushed efficiency.

Now, facing the same pressures, U.S. food manufacturers, particularly ready-to-eat and meat processing plants, are adopting the technology when designing new facilities.

“Ten to 15 years ago, sanitation was the last thing plants thought about. They would get to the end and think, ‘Oh, we need to clean this place,’” Ogren said. “It’s great to work with a company like Borton because they decided to put food safety first.”

Design and data

For the line itself, Borton turned to Aweta, a Netherlands-based supplier of sorting and packing equipment.

“We wanted a company that would work with us to develop some of these food safety things,” Leavitt said. “They were very excited to put their technology in Washington.”

Something as small as an apple sticker can make a big impact on food safety, as the stickers can get stuck on sizer cups, leaving gummy residue that’s difficult to clean off. So at Borton, all the stickers go on at the very end, Leavitt said.

“People might not connect that to food safety, but it will make cleaning so much safer,” said Faith Critzer, food safety extension educator at Washington State University, who listed the decision to sticker at the end of the process as one of the standout features of the new facility.

Even the equipment room for sanitation is thoughtfully designed, with color-coded sections to designate which tools are for which parts of the facility, and shadow boards to ensure each tool gets returned to its proper home after use. That way no one accidentally cleans a conveyor with a drain brush, Leavitt said.

Other design elements worthy of note include drying tunnels that use humidity controls and radiant heat, instead of blowing air, to dry fruit; blue belts with antimicrobial properties and a self-cleaning system; bin washers that brush and sanitize with ozone; and a robotic bin-dumping system that tips the apples gently into the water, rather than letting the bins float in the water.

He also helped design a two-phase flume system to separate the first wash from the sanitizing step. Fruit will go up a conveyor and then down into the second flume of clean water.

“It didn’t make sense to me not to have separate containment for these flumes. Your dirtiest water is right here when the bin comes in, so this system is all separate. I can dump that” he said, gesturing to the first flume and then the second, “and keep this super clean.”

That split flume design means the sanitizers applied in the second flume will be able to do a better job, said Critzer, who noted that the approach has recently been used in several other new facilities in Washington.

But one technology entirely unique to Borton is a brush-cleaning robot the company’s own engineers designed and built. It runs on a rail over the brush bed, cleaning, sanitizing and then drying.

“We knew that our biggest challenge in apple packing facilities is getting the brush beds clean. That’s where potentially the most pathogens are going to hang out,” Leavitt said. “What’s the easiest, most effective way to clean these things without changing them out? Our very own car-wash-style brush bed system.”

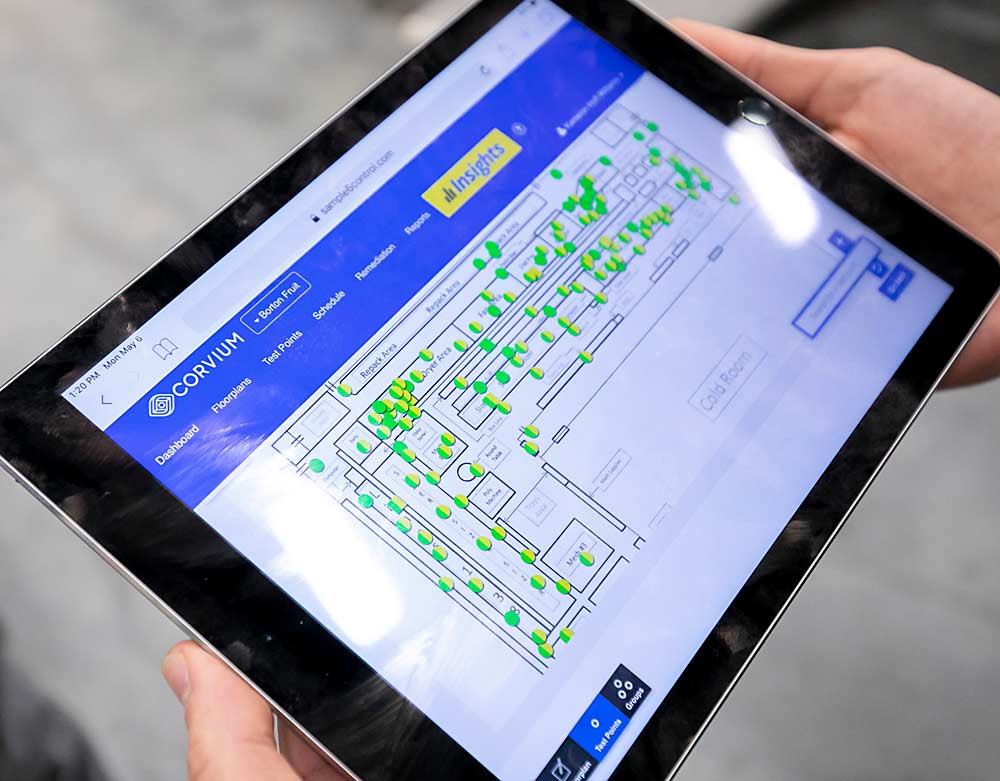

For the environmental monitoring program that ensures sanitation practices are working, Borton has gone digital. Software from Corvium tracks every test point in the company’s facilities and alerts the sanitation manager right away if a positive test result occurs, to trigger immediate remediation.

The software helps companies maintain rigorous testing, respond rapidly and keep records to be prepared for audits, said Dave Hatch, chief strategy officer for Corvium.

“Proper testing programs are designed to find it, not not find it. The key is to quickly launch corrective actions and prove and verify that you’ve addressed it,” he said.

The data from the environmental monitoring, along with the data from the centralized chemical system, means that Leavitt can track and improve the systems that keep fruit as safe as possible without a kill step.

“I can sit at my house and have full visibility of everything going on here,” he said. “I will have data to support the fact that I’m cleaning it efficiently and that I have enough pathogen testing to prove that we are selling the best quality fruit possible.” •

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment