—story by Kate Prengaman

—images by TJ Mullinax and Kate Prengaman

Water supply constraints limit South African fruit growers’ ambitions for expansion, so many are turning to tools such as protective nets, drip and deficit irrigation, mulch and dwarfing rootstocks to grow more fruit with less water.

“Water is the most scarce resource. There is a lot of land still available to plant, but there is not the water,” said Louis Reynolds, a crop consultant who volunteered as a tour guide when the International Fruit Tree Association visited the Ceres region of South Africa in December.

Managing for limited water poses one of the most significant production constraints growers face, according to Wiehann Steyn, the science director for Hortgro, the South African pome and stone fruit growers’ industry association. South Africa has always faced heat and water challenges; the changing climate is only intensifying them — and these challenges could become the reality in the Western U.S. and other tree fruit regions in the future. That’s why climate mitigation was a top topic across the IFTA’s visits to five farms in five different growing regions in the fruit-heavy Western Cape

“We’re like an open-air laboratory for people who want to see how climate changes affect fruit production,” said Steyn, who helped organize the tour.

The solutions growers are adopting vary depending on their crops, local climates and soils, and their willingness to be on the leading edge of change, he said.

“South Africa is really a country of diversity. It’s not just a diversity of people, it’s a diversity of ideas,” Steyn said.

Hold on to your water

While growers benefit from government-run reservoirs, known in local parlance as dams, they also construct their own sizeable, on-farm dams.

“Eighty percent of our rain comes in the winter, so we need to collect it and store it for summer,” Reynolds said.

In 2018, a drought tested the limits of the region’s water management. Justin Mudge, who owns Chiltern Farms in Vyeboom, along the shores of the Theewaterskloof Dam, credited the water-holding infrastructure built by his father and grandfather, both engineers, for the farm’s ability to survive the drought.

“In 2018 (the dam) was a sand basin as far as the eye could see, down to 11 percent of its capacity … so we went into proper survival mode,” Mudge said. “I went a bit crazy building dams (on-farm) in the middle of the drought, but we did, and at the end of the year we were blessed with a lot of rains and filled all those dams up.”

To deal with the downsides of those winter rains, growers often plant trees on berms. The practice also helps make the most of limited topsoil and helps the soil warm up more quickly in the spring to jump-start the growing season, said Stephan Strauss, manager of Sandrivier Estate. The farm has nearly 200 hectares of plums planted on Marianna rootstocks on berms.

To conserve water, Sandrivier also moved away from rows of windbreak trees to fully netted blocks, he said.

Heavy mulching with wheat straw also helps retain soil moisture and is a common practice in South Africa, Reynolds said. At Dutoit Agri’s farm, orchard blocks mingle with expanses of dryland wheat, conveniently leaving plenty of straw for orchard use.

To build soils in young plantings, Dutoit typically applies 20 cubic meters of compost per hectare each year during the postharvest period and then covers that with 7 metric tons of straw, said Mico Stander, a soil scientist and consultant to Dutoit. Applying by hand after harvest means no sprayers to blow the straw away before it starts to break down, he added.

Once orchards are well established, they pull back on compost to reduce vigor but continue to mulch to help retain moisture. The straw mulch also encourages growth of fine roots near the surface, which improves nutrient and water uptake, Reynolds said.

Net effects

South Africa grows a lot of Granny Smiths — it’s the preferred pollinizer in many orchards — but sunburn can cull nearly half the crop. Similarly, sun damage can result in significant amounts of Cripps Pink and its sports, Lady in Red and Rosy Glow, failing to make the Pink Lady grade, said Graeme Krige, general manager for consulting firm Fruitmax Agri.

Krige hosted the tour at Oewerzicht Farm in a Cripps Red (marketed as Joya) planting under drape net where he said in many cases, the investment in shade netting can pay off in a season.

Growers install netting primarily to protect fruit, but the move also saves a lot of water. Hannes Laubscher of United Exports estimated the savings at 15 percent. It allows them to cut back on fertilizer as well, since the trees respond to reduced sun stress with more growth.

“Your productive curve is just a lot quicker under the nets for us,” he said when the tour visited a young nectarine block that had cropped 20 metric tons per hectare in its second leaf under fixed nets.

In older, semidwarf apple and pear plantings, drape nets are the common solution. In some orchards, the Granny Smith pollinizers can be seen under “sock” nets, single-tree, black nets just protecting the sun-sensitive green apples.

At Oewerzicht Farm, the nets go up 40 to 60 days after full bloom, and workers work under the drape nets throughout the season, Krige said. That includes leaf removal by hand, to get more color on the fruit — a practice he’s found necessary, along with reflective material, to balance out the reduced light from the netting.

“Leaf removal in our climate runs a risk, but you mitigate it with the netting,” he said.

Oewerzicht has also adjusted its pruning practices for Packham’s Triumph pears that have been grown under nets the past four years to create more open canopies. To control vigor on the 12th-leaf trees, they also make two girdling cuts each year, at green tip and 35 days after full bloom, Krige said.

Drape nets offer lower up-front costs, but the labor costs add up quickly, so on newer plantings, many growers are investing in structured shade netting.

Drip, deficits and dwarfing roots

Generally, South African growers need a little more vigor to compensate for a lack of winter chill, which stunts tree growth. But simultaneously, “vigor is the enemy of fruit quality,” as Mudge put it.

For that reason, Chiltern planted on M.9 rootstocks, which produce faster and seem particularly well-suited to Cripps Pink and its sports, Rosy Glow and Lady in Red. The tour visited one such block, planted in 2017 at 1-meter tree spacing, that harvested over 100 metric tons per hectare each of the previous two years. That’s roughly equivalent to 100 bins per acre, assuming 900-pound bins, though South African growers tend to target smaller fruit sizes for their key export markets.

“With smaller trees, we can produce the same fruit but use a lot less water than the big trees,” said orchard manager Emile Pretorius. He also supports switching from microsprinklers to drip irrigation, which helps the company stretch its water supply significantly.

Stander, Dutoit’s irrigation consultant, said that M.9 trees need water more often due to their smaller root systems.

“With the bigger trees, we have a bigger cup we can irrigate into,” he said.

Each block gets a crop factor to account for its variety, system and canopy size, Stander said, which then goes into the evapotranspiration calculations Dutoit uses for irrigation scheduling.

“We tend to give water in small sips throughout the week,” he said. Using deficits intentionally at key timings to control vigor, they pause irrigation 40 days after full bloom, until shoot growth stops, and they reduce water after harvest to push the trees toward dormancy.

At Oewerzicht, bi-axis systems are showing promise for managing vigor and offering labor efficiencies. The tour visited a 2023 planting of BigBucks Gala on G.778 rootstock that was ripening almost 40 metric tons per hectare.

“It’s very productive, high-yield efficiency (rootstock) but you have to keep your hands on it,” Krige said of the rootstock selection and the decision to split it into two leaders. “Here, it’s easy, because we can turn the taps off,” he added, referring to deficit irrigation in the rocky soil with low water-holding capacity.

Only in the past few years have South African growers really started to understand how they can be successful with dwarfing rootstocks in their own climate, said Willie Kotze, the technical manager for Dutoit. That includes selecting the right rootstock for the soils and system, training trees to fill their space, and netting to reduce sunburn and water stress.

“With climate change, a lot of countries are tapping into the expertise we have built up,” he said. He noted the region’s recent research stints with three leading, global tree fruit physiologists: Luca Corelli Grappadelli of the University of Bologna in Italy, and Washington State University’s Lee Kalcsits and Stefano Musacchi, who will be there through early 2025. It’s a real credit to the industry “to have these world-renowned researchers interested in what we are doing over here.” •

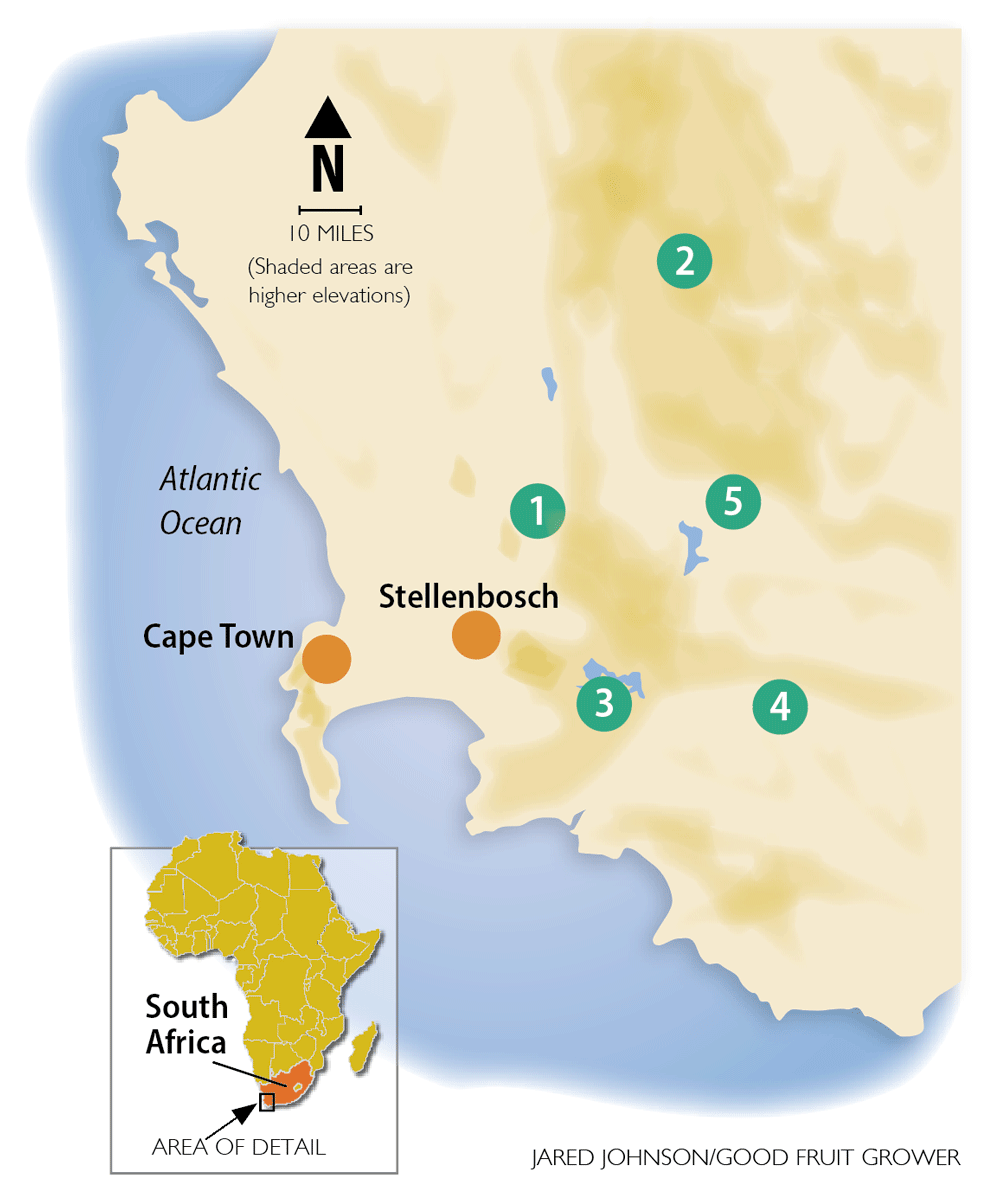

Five farms, five climates

1. Sandrivier Farm in Wellington

This orchard, owned by the Le Roux Group, features over 200 hectares of stone fruit, predominantly plums trained in a formal system. So far, 65 hectares are covered with netting, and more is planned, said Stephan Strauss, the orchard manager. The Fruit2U Packers warehouse is also located here, which handles stone fruit and table grapes from the company’s farms and, in the offseason, citrus for outside growers.

2. Kromfontein and Lindeshof Farms in the Koue Bokkeveld

These two Dutoit Agri farms, with a combined 1,000 hectares, sit in one of the country’s coolest growing regions and, thanks to higher elevation, are best suited for apples, pears and the company’s new cherry orchards. The region gets between 1,000 and 1,500 chill hours, according to technical manager Willie Kotze, but has weaker soils that make it more difficult to adopt dwarfing rootstocks. The remote orchard complex includes worker housing and a school. Dutoit, one of South Africa’s largest family-owned fruit companies, has farms in several growing regions, comprising some 5,000 hectares.

3. Chiltern Farms in the Vyeboom Valley

Chiltern Farms comprises 250 hectares of apples and pears, along with 30 hectares of container-grown blueberries, at several farm properties around the Vyeboom Valley, which is part of a large area known for pome fruit production. The region gets about 800 chill hours and features a network of reservoirs, with the larger ones run by an irrigation district and the smaller ones on-farm capturing winter rainfall for summer irrigation. Owner Justin Mudge said that in recent years, including the drought of 2018, the farm has benefitted from the fact that his father and grandfather were engineers. The company also packs and markets, with its partners, for 17 other area farmers.

4. Oewerzicht Farm in Greyton

At this warm location that pushes the climatic limits of pome fruit, Oewerzicht features 55 hectares of apples and 20 hectares of pears. The fruit are packed and marketed by the Two-A-Day Group, a company based in the Elgin district that handles 110,000 metric tons of apples and 26,500 tons of pears annually. Oewerzicht farm gets 200 to 300 chill units a year, according to Graeme Krige, a technical consultant for the Two-A-Day Group, and relies heavily on rest-breaking agents. The farm hosts several cooperative and industry trials of varieties and rootstocks.

5. Oudewagendrift Farm in the Nuy Valley

The warm Nuy Valley is best suited for stone fruit, so this farm features 30 hectares of plums and 60 of peaches and nectarines, including 24 hectares under netting, as well as a dairy operation. Tour host and owner Wilhelm Naudé said the region gets about 220 chill units annually, but modern genetics allow him to have a harvest season that runs from the beginning of October through the end of March.

—K. Prengaman

Leave A Comment