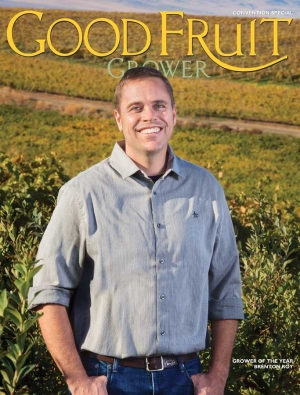

Brenton Roy in one of his Prosser, Washington orchards during the 2015 harvest. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

When Brenton Roy took over his family’s Prosser, Washington, farm, the apple and hop markets were depressed, the orchards were outdated, and wine grapes were the “shiniest crop” Oasis Farms had in the ground. He was 25 years old, and his parents had just moved off the farm, leaving it to him.

He doubled down on grapes, planting new vineyards and varieties over several years, then turned his attention to modernizing the farm’s apple orchards. Over time, he gutted the original orchards and bought additional land to plant newer varieties to meet consumer demand: Envy, Jazz, Honeycrisp, and the Pink Lady brand.

Charging into the unknown is always a gamble, but that Roy sees potential and opportunity in the untried—rather than risk—is a familiar refrain for him. He took control of the farm having had very little agriculture experience and no formal training in business or agriculture, and, years later, took a chance on a production manager who, like him, was fresh out of college when he started working on the farm.

Now 42, Roy lives in the house he grew up in overlooking a farm that he has tripled in size and modernized with new varieties, new crops, and new growing techniques—all in under 20 years. That drive and determination, along with service to the industry, have earned Roy recognition as Good Fruit Grower of the Year for 2015.

Brenton Roy, Oasis Farms

Married 16 years to wife Alicia; three daughters: Cacia, 12; Aida, 10; Ezri, 7

Married 16 years to wife Alicia; three daughters: Cacia, 12; Aida, 10; Ezri, 7

“I admit I have a minor obsession with this company. Alicia puts up with a lot. Somehow she has this inexplicable ability to understand that many days I come home and I left it all in the field, so to speak. She’s been very supportive, and she’s raised some of the best kids I’ve ever met. Bias aside there,” Roy says with a laugh.

The Good Fruit Grower of the Year award is bestowed annually by Good Fruit Grower magazine to an innovating and inspiring grower or family in North America and is presented during the Washington State Tree Fruit Association’s Annual Meeting in December. The magazine’s advisory board makes the selection.

Todd Newhouse, a fellow grower who has served with Roy on the Washington Association of Wine Grape Growers board, views him as a kindred spirit. Both studied at small, liberal arts colleges—Roy at Gonzaga University in Spokane, where he earned degrees in history and philosophy, and Newhouse at Whitman College in Walla Walla—before returning home.

The difference: Newhouse’s father is still working the land alongside him. “To take 100 percent of the reins at a young age, without a lot of experience, is phenomenal,” Newhouse said. “To not only maintain it, but to grow.”

Roy said he’s always pictured himself as the underdog, “and I think that mindset has served me very well.” It’s a cliché in this industry, he said, but farming is a constant evolution. “Either you continually improve and try to figure out how to do things better or figure out what the market wants, or you don’t and you go away. I honestly think that’s what drives the passion in this industry.” And, he added, “I don’t ever want to get complacent.”

A family farm

Roy’s great-grandfather was a migrant laborer who picked hops by hand and earned enough money to buy a plot of land in Moxee, just east of Yakima. In the 1960s, his grandfather picked up and moved the operation to the lower Yakima Valley, and over time, his father, Stan, added fruit orchards and some vineyards.

Roy, meanwhile, went away to college. He graduated, spent four months backpacking in Central America and a couple of months trekking the Himalayas in Nepal, then returned to pursue a master’s degree at Reed College in Portland. He stayed one semester before returning home to a farm that was in need of a revamp.

His father pretty much handed over the decision making to Roy, who was just 23. Two years later, his parents left the farm, his father ready to retire.

“Looking back, it’s almost embarrassingly unsophisticated how I approached how to do things, and there’s plenty of mistakes as evidence to that,” he said with a laugh. “But I had parents who saw potential in me and confidence to let me do it my own way.”

“Everything I learned about agriculture I learned here on the farm, from the ground up, because I had to,” he said. “It made for a slow start.”

Keith Oliver, who manages the neighboring orchard owned by Olsen Brothers and has served as a mentor of sorts to Roy over the years, also noted the steep learning curve to modernize Oasis Farms.

“He asked then, and still does ask, a lot of questions: ‘What are you doing? Why? Why is this density better than that density? What if the rows aren’t running north-south?’” Oliver said. “He’s obviously a smart guy, and he turned that farm around in a hurry.”

Grapes

Oasis Farms had only about 40 acres of wine grapes when Roy assumed control, but the market was strong. He spent five or six years focused on growing the farm’s wine grape acreage to meet increasing demand. At that time, he said, “clones weren’t talked about as they are now. We just planted what the wineries wanted, and we utilized the wineries’ advice about what varieties would do better at different sites: Chardonnay, Merlot, Riesling, and Cabernet Sauvignon.”

Today Oasis Farms grows 11 varieties of wine grapes, including those original plantings. Newer varieties include Malbec, Grenache, Sangiovese, and Petit Verdot. The bulk of the production goes to big players, but Oasis Farms also sells to a handful of boutique-sized wineries to work more closely with winemakers and delve into the nuances of grape-growing.

Marty Clubb of L’Ecole No. 41 in Walla Walla, Washington, sources Chardonnay grapes from Oasis Farms. Clubb said Roy recognizes that wine grapes are not a commodity crop. “It’s more about getting the right balance of acidity, minerality. Putting on that hat that changes you from a quantity crop to a quality crop is sometimes challenging, but he and his team understand the unique difference.”

Clubb said he knew Oasis Farms had potential to produce high-quality grapes, given the location and elevation of the vineyards. Then it came down to management practices: Investing in canopy management (good sunlight penetration while reducing sunburn, good spacing for airflow, no mildew), deficit irrigation management, and hand-field work to eyeball for the future, knowing the spacing of the spurs contributes to the spacing of the cluster.

“To do it right takes more investment. It’s not just machine pruned and machine harvesting,” Clubb said. “They’re willing to do all aspects to accomplish the kind of quality we’re going after.”

Apples

Investing in wine grapes and selling them under contracts helped to make the farm more financially stable and provided a foundation to reinvest in other ways.

Roy decided the farm needed to heavily reinvest in apples or exit the business; some of the planted varieties were outdated—Red Delicious, Granny Smith, Rome, and Braeburn—and there was no graftable acreage. His first orchard planting was a new block of Braeburn on M9.337 rootstock, and new varieties, including Gala and Fuji, have been planted in the years since, many as sleeping eyes.

And Oasis Farms continues to transform. That original Braeburn block he planted has since been grafted with Envy, and Honeycrisp have been grafted onto older Fuji on M.26 rootstock. Orchards also have been modernized with new growing methods, first with tall spindles, then V-shaped trellises with formal limb placement (read “New ways of doing business”).

Roy said Oasis Farms aims to aggressively reinvest in the best varieties of everything grown there, using the latest technology, with a goal to be in the top third of whatever market they’re in for that crop. “Our approach from a business perspective is to focus on topline income rather than expenses,” he said. “We’re looking for crops that are going to bring in the most money.”

In addition to trying new varieties, Roy also has entered into organic blueberries. A blueberry packing shed went into production this year.

The future

In the coming years, the few Concord grapes and stone fruit blocks will be replaced as well, as Oasis Farms focuses on four key crops: apples, wine grapes, blueberries, and hops, grown under contract to big brewers and to serve the craft brew market. He also is keeping an eye out for new apple varieties coming to market, including WA 38 (Cosmic Crisp).

“He’s got a philosophy that he’s got to turn something over every few years in order to stay up on things, so he’s always looking to pull out something old to put in something new,” Newhouse said. “It’s hard to do, and he does a good job of it.”

Roy particularly credits Derek Hill, production manager, and Chad Lybeck, chief financial officer, with helping to lead Oasis Farms into a future where the farm aims to be a key player. Roy hired Hill in 2007 straight out of Washington State University—Hill graduated on Saturday and started work on Monday. Hill said he’s grateful for the opportunity Roy gave him to learn from the ground up like he did.

“I am really excited by the fact that we continually develop every year. Making things better, looking for the best varieties, the best trellis system, how are we executing on our farm, how are we going to do better,” Hill said. “Those are things that make me proud to be part of the farm.”

Oasis Farms is a relatively youthful company, management-wise, and Roy said he and his team are enthusiastic while having high expectations for themselves. “I don’t think what we’re doing is out of the ordinary. It’s just something we’ve been successful at being completely committed to. It’s easy to say and hard to do.” •

– by Shannon Dininny

Leave A Comment