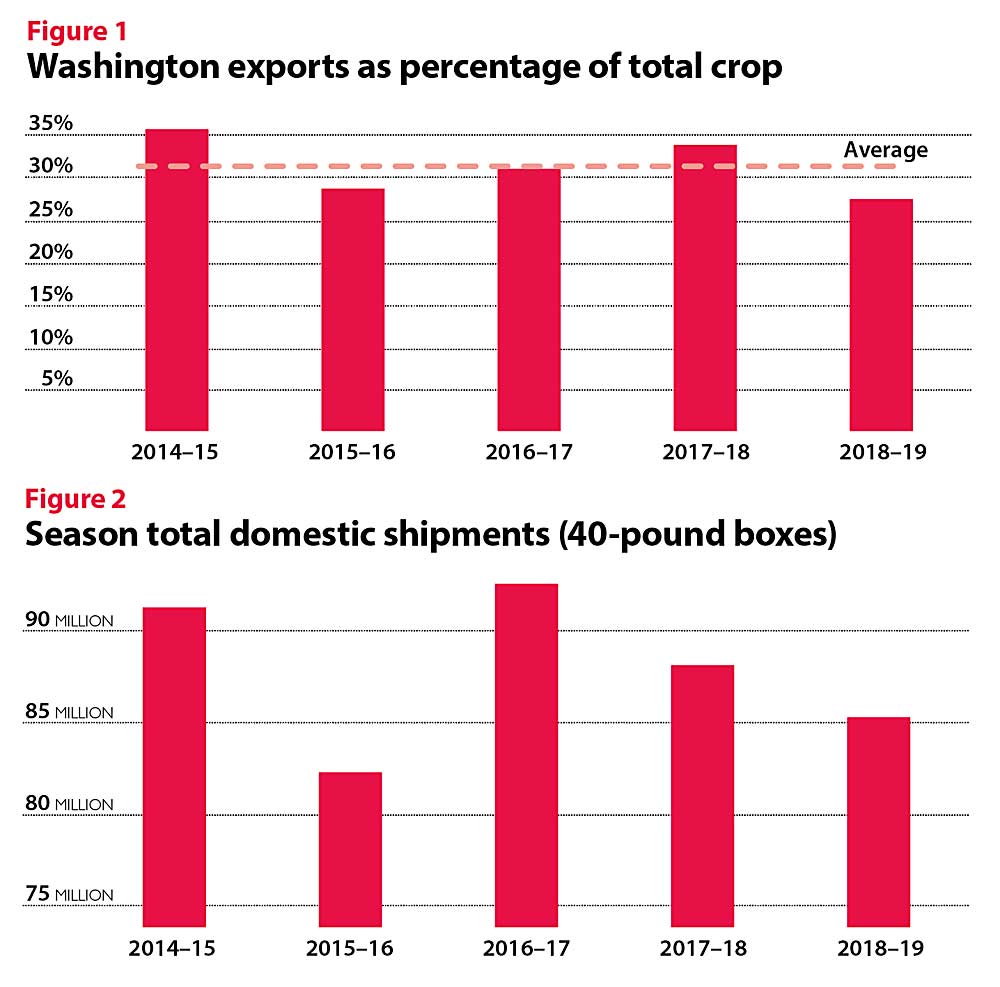

The last two years have proven difficult for Washington apple growers facing trade complications at strategic international destinations. A plethora of hurdles added to the already complicated and highly competitive international playing field: Trade challenges — specifically Section 232 and 301 tariffs, the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement and COVID-19 — have increased pricing pressure and impacted international demand. This is gravely concerning, as exports accounted for an average of 31.5 percent of sales from 2014–2019. (See Figures 1 and 2.)

Numerous Washington apple importing countries have fallen into the crosshairs of the Trump administration’s trade actions, including Mexico (the No. 1 market for Washington apples), Canada (No. 2), India (No. 3) and China (No. 7) this season. International sales have slumped to just 28.5 percent through July 31.

This is significant as trade barriers mount, redirecting supplies to the U.S. market. With domestic consumption flat and the faux promise of “a better deal” abroad, the next 24 months could reveal the full impact of past decisions within the industry. Expectations are hopeful for a return to normal trade in 2020–21, but worldwide barriers to trade (duties, pest and disease, politics and currency exchange) support the concept that we’ll have more success protecting our home court.

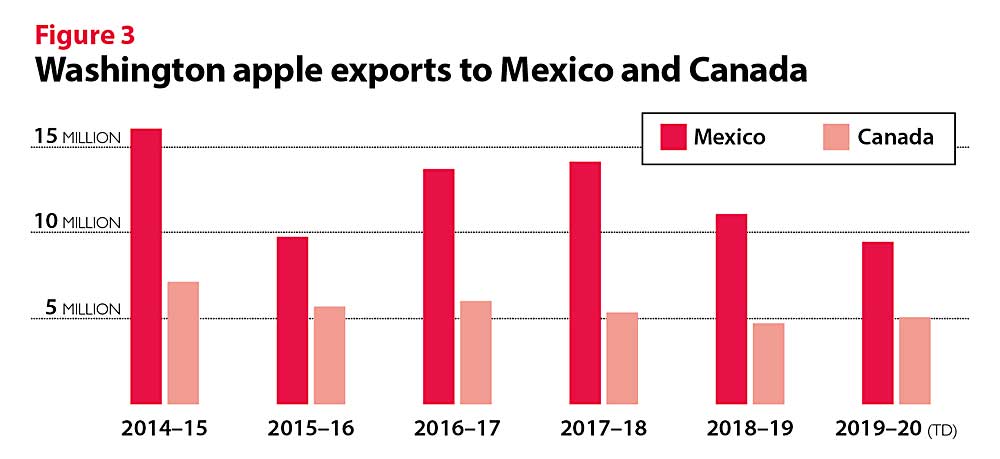

North America is our home court: the U.S., Canada and Mexico. On average, 68.4 percent of all Washington apples are consumed in the U.S. (2014–19). Mexico and Canada have accounted for 45.9 percent of all exports over the previous six seasons. In 2017–18, our home court accounted for 80.8 percent of all Washington apple shipments. Washington is the No. 1 import origin in both Mexico and Canada, accounting for over 50 percent of the apple category in Mexico alone. (See Figure 3.)

We’re in control of nothing as we export

Countries have and continue to increase barriers to trade, most frequently to protect domestic industry. The valuation of U.S. currency most often puts Washington apples at a disadvantage in comparison to other apple origins such as Chile, New Zealand, China, the EU and Eastern Europe, whose currency valuations have fallen against the dollar. Importers pay in U.S. dollars, and as other currencies fluctuate down comparative to the U.S. dollar, we become less price competitive, relying exclusively on high quality and food safety as our unique selling points. Washington will never be the “low cost producer” — inputs continue to become more expensive and labor availability is stretched to a breaking point. International opportunity is impacted as other apple origins backfill our departure with less expensive options.

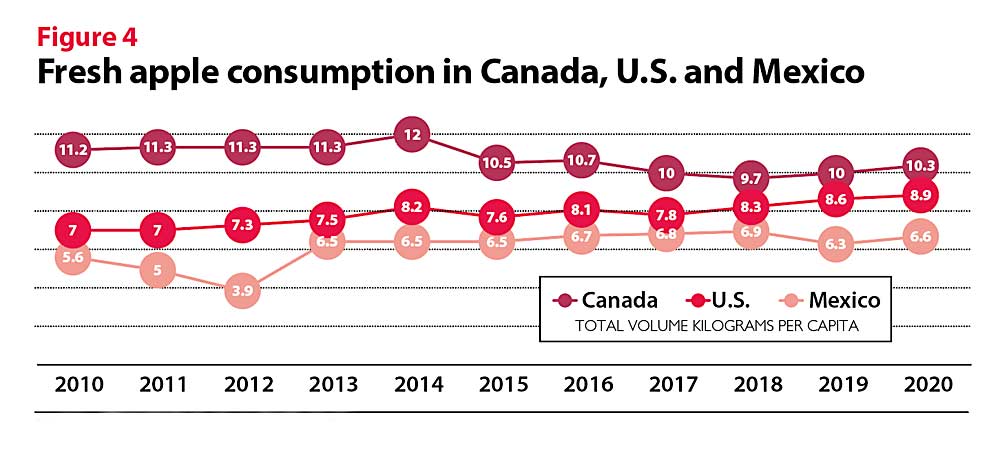

Washington’s international strength is a recognized and trusted brand, world renowned apple quality and a taste and texture for everyone. The Cosmic Crisp tsunami a few years forward will create new opportunities in the marketplace as consumers engage. But the underlying concern is the trade-off when consumers try any new variety: They necessarily aren’t purchasing more apples, just different ones. This is at the core of our need to improve per capita consumption in our home court. COVID-19 seems to have positively impacted domestic demand with increased volume and packaging alternatives, but pricing remained static with long-term consumer trends unknown. This is the fundamental issue: In our home court, per capita consumption is not increasing, and we’re exposed to unpredictable international barriers to trade. (See Figure 4.)

As you can see, there is PLENTY of room to increase per capita consumption in the U.S. You could easily argue new flavorful and crisp varieties will move the needle alone. New varieties also tend to have higher input costs requiring better-than-average price support from consumers. Although a figure isn’t available, arguably most growers have high expectations for improved returns with new varieties — rightfully so.

However, as you analyze international opportunity, with a few exceptions (Taiwan, China, Vietnam and Indonesia), prices need to be no higher than $24 per carton or, more realistically, $18–22 to capture volume business. Washington’s average export volume over the last six years is 31.6 percent. Every market has pockets of unique high-paying importers and retailers. The difference today is that all apple origins (EU, Eastern Europe, China, New Zealand and Chile) recognize this and promote heavily.

To rehash a previous commentary supported by the embarrassing per capita consumption in the U.S., the industry would benefit from a Washington campaign to support branding and improve per capita consumption. Such domestic activities are not within the scope of the Washington Apple Commission mission statement, but there is an effort underway, by a third party, to figure out how to execute this strategy with voluntary assessments. We support this approach and are hopeful of success.

The industry’s direction should be to protect and improve consumption in our home court. The WAC is realigning current export programs to support this direction. We’ve made a commitment to increasing our presence in Canada, recognizing the willingness of Canadian consumers to pay more, support organic production and experience new varieties. The Mexico program is also amplifying consumer-focused, value-added marketing campaigns to elevate consumption. I remain optimistic for a return to normal in 2020–21. •

—by Todd Fryhover

Leave A Comment