In the high-end wine world, hybrid grapes have long had a bad rap, but there are signs of growing acceptance for a new generation of disease-resistant hybrids.

In contrast to pretty much every other crop out there, wine growers tend to eschew new varieties in favor of traditional cultivars bred in Europe centuries ago, despite the fact that they are highly susceptible to fungal diseases from the New World, namely powdery mildew and downy mildew.

Native North American grapevines have much more resistance, since they evolved with the pathogens, and breeders have exploited that, through hybridization, for more than a century. Such hybrids helped European growers replant in the wake of phylloxera. But phylloxera-resistant rootstocks and modern fungicides enabled growers worldwide to grow V. vinifera successfully and pushed hybrids back out of the market: production fell from 400,000 hectares in France in the 1950s to just about 6,000 hectares today. (A hectare is nearly the size of 2.5 acres.)

Today, wine grapes comprise about 25 percent of all pesticide applications in the EU, despite only accounting for 3 percent of the agricultural land, said Christophe Schneider of the French National Institute for Agricultural Research, INRA. Last year, INRA released the first four varieties from a breeding program aimed at providing durable resistance to downy and powdery mildew. The four were registered in the Official French Catalogue.

That’s good news for everyone interested in using new grape cultivars to improve viticulture, from resistance to Pierce’s disease in California to cold tolerance in the Midwest, said Cornell University grape breeder Bruce Reisch, who himself is working on the genetics of powdery mildew resistance.

“Generally, the New World is more accepting of change and finding the right varieties for the right situation, and that’s hard where tradition is part of the culture,” Reisch said. “A lot of people are really taking note of the fact that the landscape is changing in Europe, and I get a lot of encouragement from the fact that people in Bordeaux are growing hybrid grapes.”

New cultivars vs. tradition

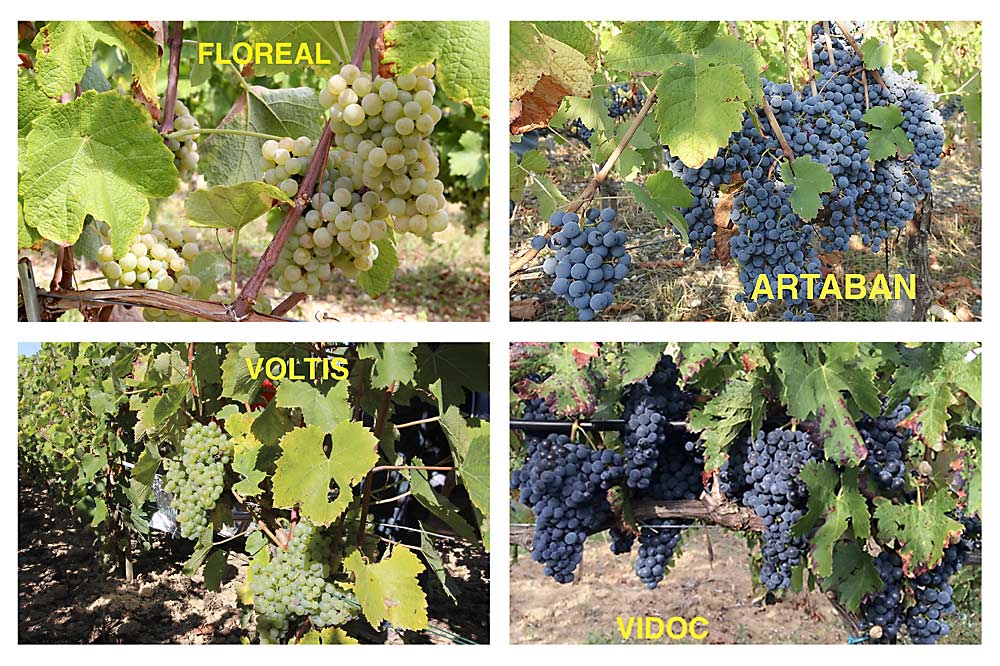

The new INRA varieties include two whites, Floreal and Voltis, and two reds, Artaban and Vidoc. Demand for them appears strong, Schneider said, with about 200 hectares planted or planned from 2018 to 2020. In 2021, the varieties should be available in the U.S. as well.

But don’t call them hybrids.

INRA calls the program “ResDur,” short for durable resistance, the name of the breeding program that’s expected to turn out about a dozen more cultivars in coming years. (In this context, durability means the cultivars carry multiple genes for resistance, to make it harder for pathogens to adapt and overcome that resistance.) And PIWI International, a cooperative of groups from more than a dozen countries that advocate for disease-resistant wine grapes, calls them “PIWI varieties.” The term PIWI comes from the German word meaning “to resist fungus.”

There are about 5,000 hectares of PIWI varieties in Europe, mostly in Northern Europe where the wetter climate increases the risk of powdery and downy mildew, said Sonja Kanthak, an organic viticulture researcher in Luxemburg and PIWI board member. That includes popular Regent and Cabernet Blanc, which were released in the 1990s. Kanthak says they aren’t hybrids, but rather, V. vinifera-like grapes that carry disease resistance and not much else from hybrid parents.

“The word hybrid is a big block, I feel; it’s like a way of saying these are lesser-than,” said Tim Martinson, Cornell viticulture extension specialist.

The early French-American hybrids weren’t made with the best French cultivars as parents and carried too many unwanted flavors and acidity from the American grapes. But now, genetic tools such as DNA markers and mapping allow breeders to, over successive generations, bring resistance genes into a grape that is otherwise almost entirely V. vinifera, Reisch said.

“In New York, we have the complication of cold hardiness, and I can’t select for vinifera without losing that,” he said. “But in France and Germany, they just need to bring resistance into vinifera and there’s lots of new stuff that can be done that gives us advantages over the original hybridizers.”

And in California, grape breeder Andy Walker released four new cultivars in 2017 that carry resistance to Pierce’s disease from V. arizonica, but otherwise are 98 percent V. vinifera.

“I’ve tasted some of the wines and they are right up there with the elite, North Coast wines people like. They are not going to have the same names, but in terms of quality, they are right up there,” Martinson said. “But could you sell a Napa Red for $150 a bottle? Probably not. There is still a lot of viticultural snobbery.”

Even in the Eastern U.S., where native grapes and hybrids provided the foundation for viticulture, wine producers tend to move toward V. vinifera varieties for prestige. But Reisch and Martinson hope increased acceptance in prestigious European growing regions will trickle down to increased interest in the powdery-mildew-resistant grapes they are developing in New York.

Marketing new wines

The changes in Europe — new cultivars, easing of anti-hybrid regulations — are promising, but it’s still going to take time for winemakers to embrace change, Kanthak said. Whole regions have built their reputations around certain grapes, but the industry is increasingly recognizing that disease pressure and climate change both threaten those traditions.

“If you think about how long we’ve known Pinot Noir and how long we’ve known how to work this grape, we don’t have the same experience with PIWIs. We had to learn and get better,” she said. “Now, there are winemakers who plant only this.”

The PIWI organization hosts annual wine competitions to introduce the varieties and trade shows to help wine growers and makers learn which cultivars would perform best for their site, region and wine style.

The name also helps. One of the more successful PIWIs in Europe is Cabernet Blanc, a white grape from a cross between Cabernet Sauvignon and a hybrid, Kanthak said. “The name gets in your mind, and it really is in the Sauvignon style. It catches the consumer’s imagination.”

Moreover, the marketing can be tricky. While wine growers are motivated to reduce pesticide use, promoting the new cultivars on the basis of that environmental benefit runs the risk of alarming consumers about the pesticides applied to traditional cultivars, she said. People want organic produce, but they don’t usually think of wine the same way.

“For me, and I know that for most of the organizations that want to support the cultivars, we want to use it in a positive way, it’s a new taste to try,” she said. “It helps to speak about the advantages of the grapes, not the plant protection products.”

Many signs suggest that the newer generation of wine drinkers across the world are more eager to try new things — adding momentum to opportunities for the industry to adapt with new-generation hybrids.

“It’s a testament to the technology we have to develop these new grape cultivars for sustainable wine production. It all makes economic and environmental sense,” Reisch said. “But none of this will make sense if people can’t sell the product.” •

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment